- Cover illustration for book: a lovely picture of a small house, two

young ladies, two young men, and one older woman hovering about a bench.

Firm's name in playful lettering across the top.

- '"Please Ma'am, can we have the Peas to shell?"'. Source: 1997 Trollpe

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, Frontispiece. My

comment: Mrs Dale depicted as very young, but point is more effective.

She has given up a great deal to allow her daughters to live the lives

of comfortable gentlewomen; see my Trollope on the Net, Chapter

6.

- ""And you love me!" said she'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. My comment:

Amelia demanding that Johnny confess her love for him; holding out letter

as 'incriminating' evidence. Moment looks much harder, no sense of

comedy, but this is also the way the scene is meant to be read.

- 'The Beginning of the Troubles', Vignette for Chapter 7. Source: N.

John Hall, Anthony Trollope and His Illustrators, p. 58:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

Exquisitely love depiction of two elegantly-dressed ladies,

with long capes, holding parasols over their heads, fashionable hats,

bell shaped skirts. They look over a fence into a field, itself an

instance of the psychological picturesque as described by Wylie

Sypher (see my bibliography of art books)

- '"It's all the fault of the naughty bird"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 66.

Millais depicts the men just before they go off to shoot;

the animals are blamed for the uncomfortable state of mind produced by

Crosbie's disappointment that Lily will not be inheriting a substantial

sum of money from the Squire.

- '"Mr Cradell, your hand", said Lupex'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 102.

Millais spends time depicting the down-and-out quality

of Mr. and Mrs. Lupex's clothing. Her clothes are once elegant, now

shabby; his hair is awry. Cradell is given a far too sweet expression

on a plump face.

- '"Why it's Young Eames"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon

of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 136.

This ought to be better known because it centers the reader's attention

on John Eames in a reverie. Lord, thinking out the letter he must write

to Amelia, and putting out of his mind Lily Dale. The Earl is made

too much of a buffoon. Effective 1860s golden style background landscape.

- '"There is Mr Harding coming out of the Deanery"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 154. Reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

pp. 70-72.

Hall praises the drawing of Mr. Harding, but I

think it is somewhat absurd. Millais has tried to convey Mr. Harding's

humility as if it were a physical posture he presents to the world;

the result is a simpering ludicrously small and thin old man who seems

to be sneaking by those who stand firmly in front of the church porch.

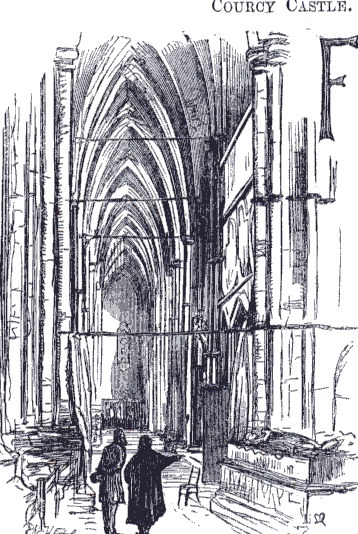

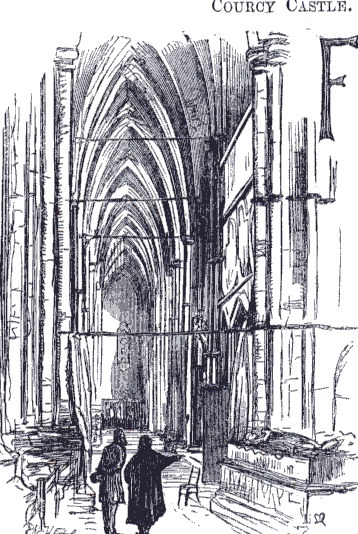

- 'Mr Crosbie meets an old Clergyman on his Way to Courcy Castle':

Vignette for Chapter 16. Source: Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 59; reprinted in reduced form in 1997 Trollope Society editon of The

Small House at Allington, p. 157:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

This is a superb depiction of

inside of a cathedral built in gothic style; two tiny figures seen

talking, drawn with shadowy strokes. Suggests a moment of peace, of

retreat in which Crosbie could have changed his mind and not gone to

the castle where he would betray his better self as well as Lily.

- '"And have I not really loved you?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 186. Reprinted

and discussed, together with photograph of original pencil drawing, Hall,

AT and His Illustrators, pp. 57-61:

John Everett Millais, John Eames and Lily Dale, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, John Eames and Lily Dale, The Small House at Allington

The original pencil

drawing shows Millais deeply engrossed in the hesitant yet intense

emotion of the scene. It is of John Eames and Lily just at the moment

he has learnt of Lily's engagement and cannot resist coming to tell her

he loves her nonetheless. The depiction of Johnny just at this juncture

(between Crosbie's adventures) brings home to the reader his centrality

in the novel. Effective choice and depiction.

- 'Mr Palliser and Lady Dumbello'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 228. This

one has been reprinted many times, e.g., Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 71; Trollopiana, 42, p. 19; Margaret Markwick, Anthony

Trollope and Women, p. 79.

Perhaps it interests people

as the first depiction of Plantagenet Palliser; he is a shy tall blond

man; Lady Dumbello sits regally in a ostentatiously luxuriously sewn

skirt; she has a big bosom, and it's lightly suggested her gown

is low-cut. She looks out at the world with cold disdain.

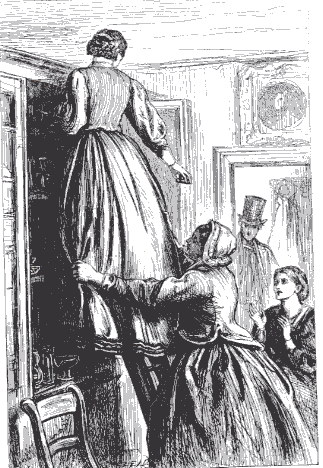

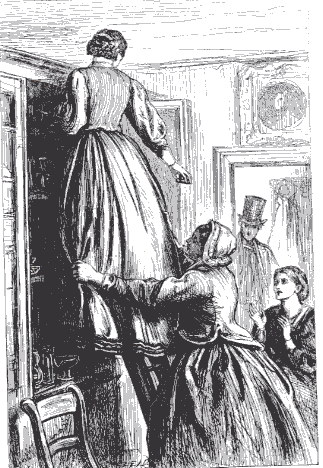

- '"Devotedly attached to the young man!"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 242. Reprinted

and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 64-69; reprinted

Markwick, AT and Women, p. 113.

While grim, hugely

over-grown older women who looks as if she has just swallowed a lemon

may seem absurd to modern viewer, women of Lady de Courcy's class prided

themselves on their size; the small emasculated male is also not exactly

a frightening bully of a male figure; however, the discontented realities

of families invented to aggrandise the network are made clear.

- Vignette, probably for Chapter 16, 'Adolphus

Crosbie spends an Evening at his Club. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, p. 250, printed

at the close of the chapter.

John Everett Millais, Young Man in a chair, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, Young Man in a chair, The Small House at Allington

An excellent one which really could be Johnny Eames or Adolphus Crosbie, but is probably Adolphus. Able drawing of young man in mid-twenties.

- 'The Board'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon of The Small

House at Allington, facing p. 278. Reprinted Hall, AT and His

Illustrators, p. 68:

John Everett Millais, "The Board", The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, "The Board", The Small House at Allington

A remarkably good depiction of

a group of men, one leaning on a mantelpiece, another sitting in

a chair, a third standing with his hands slightly upraised, all

elegantly dressed. Their expressions are banal, unexpressive in

just the way life is, even when the most ultimately shattering

experiences happen. The male figure by the mantelpiece is one of

the truest figures in all Millais; it's not overdone. For once

not theatrical. The somewhat debauched silent inured man.

- '"Won't you take more Wine?"' Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon of The Small

House at Allington, facing p. 304.

This is a scene

which recurs among the many illustrations to Trollope's novels (see

above Orley Farm; in my judgement this is good: again the

faces have vivid expressions without any exaggeration or theatricality.

They are in a state of enduring life as it passes with some glasses

of wine and a pretense of companionship to help them on. This depiction

also helps to remove the novel from the sphere of sheer feminine romance

(the chapter title is 'The wounded Fawn').

- 'The Combat': A Vignette of Adolphus Crosbie, this time in

shadows by a clock, probably for Chapter 35. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, p. 340:

John Everett Millais, Adolphus Crosbie, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, Adolphus Crosbie, The Small House at Allington

The depiction refers us back to Crosbie's distaste for

his new life among the Gazebees, his shame both at his choice and

(in a few minutes of text) at the beating he takes, partly because

he was unprepared. A good drawing, mood right; it ought to be

better known and placed where it belongs.

- '"And you went in at him on the station?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 338.

Cradell admiring Johnny after he has beaten Crosbie up at the

station. The problem here the situation of the pair (outside), their

clothes (super-elegant gentlemen), and the surrounding passersby have

nothing to do with the conversation between the two clerks in the office.

- 'Old Man's Complaint': Vignette for Chapter 37. Source: Hilary Gresty,

'Millais and Trollope: Author and Illustrator', The Book Collector,

30 (1981), p. 56, discussed p. 54.

An effective depiction of

Squire Dale, small, his hands in his pockets, his face turned towards Mrs

Dale whose face is bowed, troubled. This and the next picture turn

the reader's pictorial attention towards the old man and older woman

in the novel who are also important presences and have stories of

their own too.

- '"Let me beg you to think over the matter again"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 366; reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 67:

John Everett Millais, "Squire and Mrs Dale, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, "Squire and Mrs Dale, The Small House at Allington

While again Mrs Dale seems too young and pretty,

and her gesture and facial expression too theatrical, and Squire Dale

more the elegant gentleman than Trollope's text warrants, the mood of

the scene, the effective alive trouble on the detailed face of the

man brings home to us the struggle in this novel has also been between

these two people.

- '"That might do"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 400. Reprinted and discussed

Hall, AT and His Illustrators, p. 63:

John Everett Millais, "'That might do'", The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, "'That might do'", The Small House at Allington

This one

has been reprinted many times: it depicts the two de Courcy women giving the

proprietor of a carpet stor a hard time; behind them Adolphus Crosbie

looks at his watch. The irony is the two women haven't the money for

this, yet the very purpose of their existences seems to be at the

center of such scenes. The proprietor stands by, used to it. Millais

has lavished detail on the shelves of merchandise, the clothing, the

absorbed state of mind on the faces of the two women, one leaning down

and the other drawing back in their states of (self-)worship.

- '"Mamma", she said at last, "It is over now. I'm sure"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 424.

The scene does not come off. The details of the

room are well done; but Lily's face seems detached from her body (at

an odd angle). Only the mother is seen vividly, from the back.

- 'Valentine's Day in London': Vignette, a depiction of an elegant

street in London, probably placed at the beginning of Chapter 45. Source:

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington,

p. 467:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

The irony of the Saint's Day being the focus of

this chapter (and the one at Allington) is made clear in the full-page

illustration to this number.

- '"Why on earth on Sunday?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 452. Reprinted and discussed

Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 64-69; reprinted in Markwick

AT and Women, p. 105.

This one is often reprinted

and discussed because it dramatises an important moment between Crosbie

and Alexandria, that in which he cannot prevent himself from protesting

how they are going to spend their Sunday -- visiting people he can't

bear and she gets no visible enjoyment out of. Her face is overdone;

she looks like she has a toothache on the side of her face. This

is the life people live within the elegant buildings depicted at the

opening of the chapter -- the true price for the place.

- '"Bell, here's the inkstand"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 494. Reprinted Markwick,

AT and Women, p. 99:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

The point is

to show us Lily making do, getting used to it. The chapter heading is

'Preparations for Going'. Far from taking satisfaction in Lily's

tasks, we are to see the realities of the hard life she could have

lived had her mother not given up what she has to live on Squire

Dale's property; they are moving to a smaller place and lower position

in society. The picture is a good one, well drawn, not overdone.

- '"She has refused me and it is all over"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 518.

Reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp.

57-62; also repritnted, James Pope Hennessey, Anthony Trollope,

from the Mansell Collection, p. 250:

John Everett Millais, Lady Julia and Johnny Eames, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, Lady Julia and Johnny Eames, The Small House at Allington

This scene between Lady Julia and Johnny Eames ends the book. Millais

has done justice to the old woman's face: she is old, stiff, but

beautifully concerned for the young man who looks down at the water.

The piece is tastefully done, from the realistic everyday clothes to the

bare spring landscape to the understated emotions of the figures.

- 'The Fate of the Small House'. Vignette which shows us the small

house, probably for last number, Chapter 58. Source: 997 Trollope

Society edition of The Small House at Allington, p. 527:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

It looks very like a small version of Orley Farm.

Volume I (all by Phiz)

- 'The Balcony at Basle'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, Frontispiece. Reprinted Hennessey,

p. 297:

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), The Balcony at Basle"

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), The Balcony at Basle"

Very effective piece of line drawing. We see

George and Alice Vavasour by the water's edge on the balcony; it is

a pivotal moment in the novel. The faces are alive with feeling which

is psychologically ambiguous, calm, quiet, intent. The mood is one

of languor and dream.

- '"Would you mind shutting the window?"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 10. The scene as depicted

literally repeats some of the gestures in the scene, but the piteous look

on the old woman's face and the disdainful calm on the young woman's is

not at all appropriate to Alice Vavasour's vexation or her aunt Lady

Macleod's peremptory indignation and demands. As a drawing of figures,

it's accurate. Alice is given dark hair.

- '"Sometimes you drive me to hard". Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 26. This is

laughably wrong. Kate is made lachrymose and disdainful, while Alice

looks lifeless. Phiz does not seem to have understood the pyschology

of the serious scenes in the novel at all.

- '"Peace be to His Manes"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 60. This one is

supposed to be funny. The widow looks really grief-striken; she is

made large and still. The maid has a certain living curiosity in her

face. Kate seems to be asking herself what she should do next.

The idea of a inward disparity between gesture and psychology which

has subtle yet parodic implications is beyond this artist.

- '"Captain Bellfield Proposes a Toast". Source: 1989 Trollope Society

edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 78. Reprinted and

discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 93-94.

This external scene, with its vivacity, comic gestures, and sense of energy

which can be caught through lines adds life to Trollope's own scene.

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Captain Bellfield Proposes a Toast"

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Captain Bellfield Proposes a Toast"

- '"If it were your friend what advise would you give me?"' Source: 1989

Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 100 .

Another one within Phiz's range as the outward gesture does

reflect the inward reality of the scene. There is a nobility in John

Grey as he speaks (though the male figure's face is made too old,

too many lines given)l there is an appropriate dullness in Alice's face.

- '"I'm as round as your hat, and as square as your elbow; I am"'.

Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?,

facing p. 112.

Phiz's art cannot accommodate the seriousness

of Trollope's depiction of Grimes with its sardonic yet realistic

humour; Grimes becomes a kind of mild silly-smiling caricature of

a round man. This does for Cheesacre, not for grasping practical

and ruthless nature of Trollope's slightly cringing campaign manager

as he explains himself to George Vavasour. Scruby too much the

gentleman and too old. George maintains the beard from the frontispiece.

- '"Mrs Greenhow, look at that"". Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 121. This does not

come off. The widow looks like she is holding marbles in her mouth; her

eyes are closed. Cheeseacre looks detached, relaxed. Not comic.

- 'Edgehill'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You

Forgive Her?, facing p. 148. Reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His

Illustrators, pp. 96-98:

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Edgehill", Can You Forgive Her?

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Edgehill", Can You Forgive Her?

This is the second hunting

scene (of four in all Trollope's novels); it constitutes one of the

two most frequently-reprinted of the original illustrations to Trollope's

novels (for the other, see Annotated Commentary I, 'Monkton Grange' by

Millais for Orley Farm). As with Millais', it is attractive,

filled with energy, verve. It is more successful than Millais', if a

sense of movement is what's wanted. As said above, the attention paid

to such a piece belies the reality and nature of Trollope's novels

centrally, of the gist of their stories and characters.

- '"Arabella Greenow, will you be that woman?" Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 184.

This depiction of Mr Cheesacre asking Mrs Greenow to marry

him has a delicacy of approach in the lines given Mr Cheesacre's

face. The widow sits on a couch and appears to be barely paying

any attention to him at all. Again it's not bad because the outward

gesture can stand for the inward reality.

- '"Baker, you must put Dandy on the bar"'. Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 194.

This elegant depiction of Lady Glencora's carriage and

beautiful horses strikes the note of luxury and animal life wanted.

The problem is Lady Glen's face is without life.

- '"Mr Palliser, that was a cannon"'. Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 209.

Again Phiz seeks the note of luxury, of elegance, of

wealth in the clothes, the depiction of the billard table. We

have a crowd; a man stands on the side in earnest talk with a

female who seems to be coyly looking within herself.

- '"The most self-willed young woman I ever met in my life"'.

Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?,

facing p. 242. Reprinted Trollopiana, 27, p. 29.

This has the same problem the earlier depiction of

Alice versus an older woman has: the older woman becomes a comic

caricature who looks sad and bewildered, not at all an oppresive

figure. Alice appears to be quietly thinking to herself. Phiz's

art cannot accommodate complex psychology of resentment, domineering,

without exaggeration, and exaggeration is what Trollope didn't want.

- "The Priory Runs". Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 246. This one deserves

to be better known; it is an instance where Phiz reaches for and

obtains through lines the psychological picturesque. The lovely

playful depiction of the greenery, the dissolving gothic arch provide

an appropriate frame for the blond young woman who looks down

at the ground with a resentful dismayed expression. Alice's

larger figure comforting her looks forward to Mary Ellen Edwards'

depiction of a similar scene between Julia, Lady Ongar and

Florence Burton at the close of The Claverings (see

Annotated Commentary 3, 'Lady Ongar and Florence' and my

Trollope on the Net, Chapter 5.

- 'Burgo Fitzgerald'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 262. Reprinted and discussed

Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 91-93. Also reprinted

Hennessey, p. 253; the frontispiece to my Trollope on the Net:

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), Can You Forgive Her?

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), Can You Forgive Her?

Once again the outward gestures really mirror the inward

realities of the scene -- as do the costumes. However, this does not

account for the reality that this is arguably one of the best of the

original illustrations of Trollope's novels. As with Millais's

'Lady Mason after her Confession' for Orley Farm

and Stone's 'Trevelyan at Casalunga' for He Knew He Was Right

(see Annotated Commentaries 1 and 3), the artist has himself entered

the inner reality of the participants in ways that are closely

analogous to Trollope's own in his novels. See Trollope on the Net, Chapter 6.

- 'Swindale Fell'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of

Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 284:

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Swindale Fell"

Hablôt Browne (Phiz), "Swindale Fell"

This

has all the graces and attempt at inward interest of 'Priory

Ruins', but the deep-musing nature of Trollope's use of inner

light and the two women intent upon letters and memory cannot

be accommodated in the distanced line flat line drawing with

small figures. See my discussion in Trollope on the Net,

Chapter 6.

- '"I have heard -- said Burgo"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 300.

This scene

of a group of men around the table is awkward and has no central

mood. The Burgo figure looks pettily annoyed; Cosimo Monk looks

startled in a comic way; one male with long moustaches has a pained

expression on his face. Phiz does not know what to do with such

a complicated depiction of psychologies interacting through social

gestures.

- '"Then -- then -- then let her come to me"' Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 330.

John Grey now too young and too theatrically melancholy;

Mr Vavasour too graceful and conventional a figure. Phiz is trying

for the gesture of loyalty amid companionship between two men.

- '"So you've come back, have you?" -- said the Squire'. Source:

1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing

p. 351. This one does not come off at all. Squire Vavasour looks

weak and sadly dismayed, not angry, not indignant. There's no energy

here. Goerge is expressionless, overshadowed by his hat. Kate

looks away, a kind of pinhead on a cape.

- '"Dear Greenhow! dear Husband!"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society

edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 368. This one

is occasionally reprinted in studies of book illustrations and Victorian

comic depictions of social life, though not in Trollope studies.

It is effective. Phiz has a feel for Captain Bellfield as a devil-

may-care scamp; he is depcited a man in his thirties, a bit tired,

but looking at Mrs Greenow with a kind of gallant fondness and

animation. Behind the couch on which Mrs Greenow and the Captain

sit, we see Kate conversing (from the side) with a slightly dismayed

Cheesacre. The comic expression seems right. The irony is Mrs

Greenow is lamenting over her husband's picture. But for his

money none of this would take place. She's enjoying it.

Volume II (all by Miss E. Taylor)

- 'Great Jove'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You

Forgive Her?, facing p. 382. Reprinted and discussed Hall,

AT and His Illustrators, pp. 98-99.

It's a match

in mood and significance for Millais's 'The Board' (see above,

The Small House at Allington). It is good because it too

captures the banality and indifference of everyday life in Parliament. The man who holds the position and wears the clothes

others so want sits and sleeps; others talk and argue and kill time

as they can. There is reality in the psychology of the faces.

- "Friendships will not come by ordering", said Lady Glendora'.

Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?,

facing p. 388. Miss Taylor's Lady Glen is much larger, rounder,

impressive; unfortunately, the expression on her face isone of silent

annoyance instead of poignant resentment as she tells the simple

truth.

- '"I asked you for a kiss"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 426. The

psychology of George's face all wrong. He does not look frightening,

only distressed. He leans over as if to make an impression, and

Alice sews on as if she feels nothing but a slight upset. The depiction

of brutal violence is not found in any of the illustrations to Trollope's

novels -- though it happens frequently enough in his stories.

- 'Mr Cheesacre disturbed'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 435. In her

rounded psychological in-depth style, Miss Taylor reaches for the

same mood and sources of comedy we find in '"Dear Greenhow! dear

Husband!"'. Perhaps the thinner figures are more effective; Miss

Taylor's faces are not as alive; her Captain Bellfield is too

sentimentally engaged around the eyes.

- '"All right,", said Burgo, as he thrust the money into his breast

pocket'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive

Her?, facing p. 449. Lady Monk is well done; her

expression of interest is just right. The figure is wholly believably

dressed. She looks slightly irritated yet expectant. The problem is

with Burgo: our insouciant rake has turned into a young plump blond

man with a sentimental expression on his curiously feminine face. right.

- 'Mr Bott on the watch'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 459. This

is not bad; the viewer's attention is fixed on the darker fully

detailed figure of Bott seeming looking at a couple slightly sketched

in the distance while he stands very close to Lady Glen seen from

the bakkc with Burgo making an intent appeal as they sit with their

faces and upper bodies facing and close to one another. Here Burgo's

face is hard.

- 'The Last of the old Squire'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 484. A death scene. The old man looks like a real old

man who has just sunk back; Kate looks weary as she watches. It is

dark, gloomy, still.

- 'Kate'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You

Forgive Her?, facing p. 517. Reprinted and discussed in

Deborah Denenholz Morse's Women in Trollope's Palliser's

Novels, pp. 35-37:>

Miss E. Taylor, "Kate"

Miss E. Taylor, "Kate"

This, 'Lady

Glencora' and 'Ailce' are discussed in my Trollope on the

Net, Chapter 6, as effective deeply-felt visualisations of

women who are being deprived of something deeply, privately-meaningful

to themselves, women in reverie. Each is detailed appropriately

and the poses are set up in parallel analogies. The one of

Kate is unusual for showing a woman just after brutal violence,

calming down.

- 'Lady Glencora'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 530. Reprinted

and discussed in Hall AT and His Illustrators, p 100-1;

Morse, Women in Trollope's Palliser's Novels, pp. 100-4:

Miss E. Taylor, "Lady Glencora". Can You Forgive Her?

Miss E. Taylor, "Lady Glencora". Can You Forgive Her?

On this: Miss Taylor has been

careful to follow Trollope's detailed visualisation of Lady Glen

at the moment she has to face her half-spontaneous decision,

which was to stay with Plantagenet and safety. It may be compared

with Millais's depiction of Laura Kennedy in Phineas Finn, '"So

she burned the morsel of paper"' (see Annotated Commentary

3). Bachelard's commentary on reveries in front of fireplaces

is also appropriate for understanding why these visualisations

take the kind of mood and show the kind of details we see

here.

- '"Before God, my first wish is to free you from the misfortune I

have brought on you"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 536. Reprinted

and discussed in Morse, Women in Trollope's Palliser's Novels,

pp. 100-4. This emphasis on Lady Glen's guilt for not

having become pregnant, for loving Burgo and not the very handsome

young lord with his kind gravity and intelligence Miss Taylor has

depicted is revealing of how the average woman of Trollope's era would

have seen Lady Glen's predicament. They took her childlessness seriously;

she was not fulfilling her duty to him. I find this illustration

touching.

- 'She managed to carry herself with some dignity'. Source:

1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing

p. 576. Again Miss Taylor has given Trollope's women

real dignity, intelligence on their faces. Alice is made sombre,

yet not theatrical. It is just right for the text.

- '"A sniff of the rocks and valleys"'. Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 581.

Miss Taylor can capture Captain Bellfield's nervousness,

but not his rakish quality. There is something emasculated about

the depiction of his body; it is enfeebled. (The Trollope Society

edition has misplaced this in a chapter on Grey and Alice.)

- '"I wonder when you're going to pay me what you owe me, Lieutenant

Belfield". Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You

Forgive Her?, facing p. 596. My comment: again, except for

the lakc of savoir-faire and nonchalance in Bellfield (who looks

merely anxious), and the still dignity of Mrs Greenow's face

(an aspect of this idyllic style), the picture is not bad. It does

put Cheesacre's indignation to the fore.

- 'Lady Glencora at Baden'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 627:

Miss E. Taylor, "Lady Glencora at Baden"

Miss E. Taylor, "Lady Glencora at Baden"

This

one should be better known; it is a superb depiction of an important

moment in Lady Glen's experience. It is alive with tension, well drawn.

There's a grim shadow around Lady Glen's face at the table which suggests

the consequences of the adventures she seeks. It is really a piece of

unfair prejudice which dismisses Miss Taylor as inadequate; it is not

even anti-feminism. She is dismissed because she is unknown, has

no name, is nobody.

- 'Alice'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition.f Can You

Forgive Her?, facing p. 644:

Miss E. Taylor, "Alice"

Miss E. Taylor, "Alice"

I discuss this one

at length in Trollope on the Net, Chapter 6; I think

interesting. Its in-depth psychological musing, the effective, beauty, and suggestiveness of the clothing, the repressed sexuality, the

longing, the loss are all superb. It is a third with 'Kate'

and 'Lady Glencora' above: the ladies all in parallel positions.

No one but a woman could understand what was in the woman's

mind; Millais doesn't come near it nor Francis Montague Holl

in their depictions of Lucy Robarts and Madame Marie Goesler.

- '"Oh George", she said, "you won't do that!"'. Source: 1989

Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing

p. 656.

On the other hand, this hopelessly sentimentalised

depiction of a fallen women is hilarious. 'Jane' piously holds

her hands together as if in prayer; she is all primness. He points

sternly to the money on the table. The lesson against sex is

made clear. George is well-drawn, and the disposition of the

figures projects the nadir mood of the scene.

- 'How am I to thank you for forgiving me?"'. Source: 1989 Trollope

Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 689.

Reprinted and discussed in Morse, Women in Trollope's Palliser's

Novels, pp. 31-33.

We return to the balcony

scene of the frontispiece; Alice is now with Grey instead of

George. I find the mood and depiction of this equally successful:

we have exchanged languor for earnestness. The two people are

now in communication, not dreaming apart.

- '"Good night, Mr Palliser"'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 700.

Our

last glimpse of Burgo from the back; we see Plantagenet extend his

hand in fellowship. The spirit of the scene is right if Plantagenet

is suddenly much older, and Burgo much smaller than in the previous

pictures. The dark wood is appropriate; this is not a comic book

at its core.

- 'Alice and Her Bridesmaids'. Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition

of Can You Forgive Her?, facing p. 724. Reprinted and

discussed in Morse, Women in Trollope's Palliser's

Novels, pp. 31-33.

I find these kinds of scenes

as depicted in the novels of the period hopelessly false; the turn

away from reality to flowerbuds and demur expressions on flat

figures all perched along an elegant stairway is striking.

- '"Yes, my bonny boy, -- you have made it right for me"'.

Source: 1989 Trollope Society edition of Can You Forgive Her?,

facing p. 736. Lady Glen's existence is now justified.

This is not as patently false as the one above. The women have

some depth of body; the looks on the faces have a certain vividness.

A great deal of effort has been expended on making the room and

furniture real.