The Small House at Allington

Written 1862 (20 May) - 1863 (11 February)Serialized 1862 (September) - 1864 (April), Cornhill

18 full-page and 19 one-quarter chapter-heading vignettes by John Everett Millais

Published as a book 1864 (April), George Smith

- Cover illustration for book: here is a black-and-white reproduction of the lightly (pastels) colored picture of a small house, two

young ladies, two young men, and one older woman hovering about a bench.

Firm's name in playful lettering across the top.

- '"Please Ma'am, can we have the Peas to shell?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, Frontispiece.

Mrs Dale depicted as very young, but point is more effective. She has given up a great deal to allow her daughters to live the lives of comfortable gentlewomen; see my Trollope on the Net, Chapter 6.

- ""And you love me!" said she'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington. Here we have

Amelia demanding that Johnny confess her love for him; holding out letter

as 'incriminating' evidence. Moment looks much harder, no sense of

comedy, but this is also the way the scene is meant to be read.

- 'The Beginning of the Troubles', Vignette for Chapter 7. Source: N.

John Hall, Anthony Trollope and His Illustrators, p. 58:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

Exquisitely love depiction of two elegantly-dressed ladies, with long capes, holding parasols over their heads, fashionable hats, bell shaped skirts. They look over a fence into a field, itself an instance of the psychological picturesque as described by Wylie Sypher (see my bibliography of art books)

- '"It's all the fault of the naughty bird"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 66.

Millais depicts the men just before they go off to shoot; the animals are blamed for the uncomfortable state of mind produced by Crosbie's disappointment that Lily will not be inheriting a substantial sum of money from the Squire.

- '"Mr Cradell, your hand", said Lupex'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 102.

Millais spends time depicting the down-and-out quality of Mr. and Mrs. Lupex's clothing. Her clothes are once elegant, now shabby; his hair is awry. Cradell is given a far too sweet expression on a plump face.

- '"Why it's Young Eames"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon

of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 136.

This ought to be better known because it centers the reader's attention on John Eames in a reverie. Lord, thinking out the letter he must write to Amelia, and putting out of his mind Lily Dale. The Earl is made too much of a buffoon. Effective 1860s golden style background landscape.

- '"There is Mr Harding coming out of the Deanery"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 154. Reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

pp. 70-72.

Hall praises the drawing of Mr. Harding, but I think it is somewhat absurd. Millais has tried to convey Mr. Harding's humility as if it were a physical posture he presents to the world; the result is a simpering ludicrously small and thin old man who seems to be sneaking by those who stand firmly in front of the church porch.

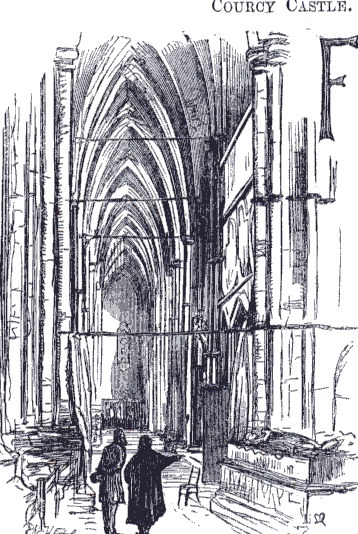

- 'Mr Crosbie meets an old Clergyman on his Way to Courcy Castle':

Vignette for Chapter 16. Source: Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 59; reprinted in reduced form in 1997 Trollope Society editon of The

Small House at Allington, p. 157:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

This is a superb depiction of inside of a cathedral built in gothic style; two tiny figures seen talking, drawn with shadowy strokes. Suggests a moment of peace, of retreat in which Crosbie could have changed his mind and not gone to the castle where he would betray his better self as well as Lily.

- '"And have I not really loved you?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 186. Reprinted

and discussed, together with photograph of original pencil drawing, Hall,

AT and His Illustrators, pp. 57-61:

John Everett Millais, John Eames and Lily Dale, The Small House at Allington

The original pencil drawing shows Millais deeply engrossed in the hesitant yet intense emotion of the scene. It is of John Eames and Lily just at the moment he has learnt of Lily's engagement and cannot resist coming to tell her he loves her nonetheless. The depiction of Johnny just at this juncture (between Crosbie's adventures) brings home to the reader his centrality in the novel. Effective choice and depiction.

- 'Mr Palliser and Lady Dumbello'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 228. This

one has been reprinted many times, e.g., Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 71; Trollopiana, 42, p. 19; Margaret Markwick, Anthony

Trollope and Women, p. 79.

Perhaps it interests people as the first depiction of Plantagenet Palliser; he is a shy tall blond man; Lady Dumbello sits regally in a ostentatiously luxuriously sewn skirt; she has a big bosom, and it's lightly suggested her gown is low-cut. She looks out at the world with cold disdain.

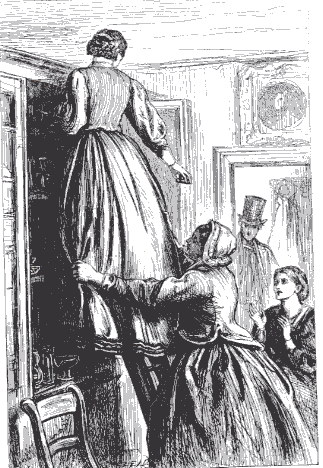

- '"Devotedly attached to the young man!"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 242. Reprinted

and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 64-69; reprinted

Markwick, AT and Women, p. 113.

While grim, hugely over-grown older women who looks as if she has just swallowed a lemon may seem absurd to modern viewer, women of Lady de Courcy's class prided themselves on their size; the small emasculated male is also not exactly a frightening bully of a male figure; however, the discontented realities of families invented to aggrandise the network are made clear.

- Vignette, probably for Chapter 16, 'Adolphus

Crosbie spends an Evening at his Club. Source: 1997 Trollope Society

editon of The Small House at Allington, p. 250, printed

at the close of the chapter.

John Everett Millais, Young Man in a chair, The Small House at Allington

An excellent one which really could be Johnny Eames or Adolphus Crosbie, but is probably Adolphus. Able drawing of young man in mid-twenties.

- 'The Board'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon of The Small

House at Allington, facing p. 278. Reprinted Hall, AT and His

Illustrators, p. 68:

John Everett Millais, "The Board", The Small House at Allington

A remarkably good depiction of a group of men, one leaning on a mantelpiece, another sitting in a chair, a third standing with his hands slightly upraised, all elegantly dressed. Their expressions are banal, unexpressive in just the way life is, even when the most ultimately shattering experiences happen. The male figure by the mantelpiece is one of the truest figures in all Millais; it's not overdone. For once not theatrical. The somewhat debauched silent inured man.

- '"Won't you take more Wine?"' Source: 1997 Trollope Society editon of The

Small

House at Allington, facing p. 304.

This is a scene which recurs among the many illustrations to Trollope's novels (see above Orley Farm; in my judgement this is good: again the faces have vivid expressions without any exaggeration or theatricality. They are in a state of enduring life as it passes with some glasses of wine and a pretense of companionship to help them on. This depiction also helps to remove the novel from the sphere of sheer feminine romance (the chapter title is 'The wounded Fawn').

- 'The Combat': A Vignette of Adolphus Crosbie, this time in

shadows by a clock, probably for Chapter 35. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, p. 340:

John Everett Millais, Adolphus Crosbie, The Small House at Allington

The depiction refers us back to Crosbie's distaste for his new life among the Gazebees, his shame both at his choice and (in a few minutes of text) at the beating he takes, partly because he was unprepared. A good drawing, mood right; it ought to be better known and placed where it belongs.

- '"And you went in at him on the station?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society editon of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 338.

Cradell admiring Johnny after he has beaten Crosbie up at the station. The problem here the situation of the pair (outside), their clothes (super-elegant gentlemen), and the surrounding passersby have nothing to do with the conversation between the two clerks in the office.

- 'Old Man's Complaint': Vignette for Chapter 37. Source: Hilary Gresty,

'Millais and Trollope: Author and Illustrator', The Book Collector,

30 (1981), p. 56, discussed p. 54.

An effective depiction of Squire Dale, small, his hands in his pockets, his face turned towards Mrs Dale whose face is bowed, troubled. This and the next picture turn the reader's pictorial attention towards the old man and older woman in the novel who are also important presences and have stories of their own too.

- '"Let me beg you to think over the matter again"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 366; reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators,

p. 67:

John Everett Millais, "Squire and Mrs Dale, The Small House at Allington

While again Mrs Dale seems too young and pretty, and her gesture and facial expression too theatrical, and Squire Dale more the elegant gentleman than Trollope's text warrants, the mood of the scene, the effective alive trouble on the detailed face of the man brings home to us the struggle in this novel has also been between these two people.

- '"That might do"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 400. Reprinted and discussed

Hall, AT and His Illustrators, p. 63:

John Everett Millais, "'That might do'", The Small House at Allington

This one has been reprinted many times: it depicts the two de Courcy women giving the proprietor of a carpet stor a hard time; behind them Adolphus Crosbie looks at his watch. The irony is the two women haven't the money for this, yet the very purpose of their existences seems to be at the center of such scenes. The proprietor stands by, used to it. Millais has lavished detail on the shelves of merchandise, the clothing, the absorbed state of mind on the faces of the two women, one leaning down and the other drawing back in their states of (self-)worship.

- '"Mamma", she said at last, "It is over now. I'm sure"'. Source: 1997

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing

p. 424.

The scene does not come off. The details of the room are well done; but Lily's face seems detached from her body (at an odd angle). Only the mother is seen vividly, from the back.

- 'Valentine's Day in London': Vignette, a depiction of an elegant

street in London, probably placed at the beginning of Chapter 45. Source:

Trollope Society edition of The Small House at Allington,

p. 467:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

The irony of the Saint's Day being the focus of this chapter (and the one at Allington) is made clear in the full-page illustration to this number.

- '"Why on earth on Sunday?"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 452. Reprinted and discussed

Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp. 64-69; reprinted in Markwick

AT and Women, p. 105.

This one is often reprinted and discussed because it dramatises an important moment between Crosbie and Alexandria, that in which he cannot prevent himself from protesting how they are going to spend their Sunday -- visiting people he can't bear and she gets no visible enjoyment out of. Her face is overdone; she looks like she has a toothache on the side of her face. This is the life people live within the elegant buildings depicted at the opening of the chapter -- the true price for the place.

- '"Bell, here's the inkstand"'. Source: 1997 Trollope Society edition of The

Small House at Allington, facing p. 494. Reprinted Markwick,

AT and Women, p. 99:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

The point is to show us Lily making do, getting used to it. The chapter heading is 'Preparations for Going'. Far from taking satisfaction in Lily's tasks, we are to see the realities of the hard life she could have lived had her mother not given up what she has to live on Squire Dale's property; they are moving to a smaller place and lower position in society. The picture is a good one, well drawn, not overdone.

- '"She has refused me and it is all over"'. Source: 1997 Trollope

Society edition of The Small House at Allington, facing p. 518.

Reprinted and discussed Hall, AT and His Illustrators, pp.

57-62; also repritnted, James Pope Hennessey, Anthony Trollope,

from the Mansell Collection, p. 250:

John Everett Millais, Lady Julia and Johnny Eames, The Small House at Allington

This scene between Lady Julia and Johnny Eames ends the book. Millais has done justice to the old woman's face: she is old, stiff, but beautifully concerned for the young man who looks down at the water. The piece is tastefully done, from the realistic everyday clothes to the bare spring landscape to the understated emotions of the figures.

- 'The Fate of the Small House'. Vignette which shows us the small

house, probably for last number, Chapter 58. Source: 997 Trollope

Society edition of The Small House at Allington, p. 527:

John Everett Millais, The Small House at Allington

It looks very like a small version of Orley Farm.

Home

Contact Ellen Moody.

Pagemaster: Jim Moody.

Page Last Updated: 17 February 2004