Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Trollope and Gender: the papers (2) · 29 July 06

Dear Marianne,

Tuesday was supposed to be a very long day. Sessions were to begin at 9 am and end at 5:30 pm; there was supposed to be a 2 hour break and then a dinner. In the event, one of the two keynote speakers didn’t show, nor did he send a paper (!) and so the last sessions for the day were moved up, a tea was offered and the day was finished at 4. Three and one half hours was too long to wait in the heat for a dinner I’d have to leave early (as there was no late train back to Lympstone from Exeter St Davids), so I went back at 4:30 and arrived at the tower by 5.

The day again opened (9 am) with a keynote address: by one of the conference organizers, Deborah Denenholz Morse. Prof Morse presented a post-colonial reading of He Knew He Was Right. There is a long detailed summary of her argument in the Programme and Abstracts for the conference; basically she argued that beyond making visible in the story of Louis and Emily Trevelyan the oppressive patriarchal power structure, one where the male seeks to control and repress the distrusted sexuality of his wife, in He Knew He Was Right Trollope uses Emily and the place she comes from to show how European males sought to imprison and quell slaves, the colonized peoples they were exploiting. She used the analogy Trollope sets up between Shakespeare’s Othello and this novel to suggest that we have a racial story. The three romantic subplots are there by contrast.

By the end of her talk she had convinced me. Strong evidence came from the descriptions of Emily (dark and passionate) and the many references in the book to England’s colonial empire as well as the characterization of Hugh Stanbury and Nora Rowley’s modern (relatively free and equal) relationship. I’m still inclined to find the analysis of the novel I present in one of the chapters of my book more central: that the Trevelyan story is one of sexual anxiety and jealousy, with an intensely frustrated wife who despises a psychologically weak if tyrannical husband, with the other three stories mirroring better and parallel situations and solutions to the problem of the interaction of dominance and submission in human relationships. Her reading added or uncovered another layer or thread of meaning running through this big complex book.

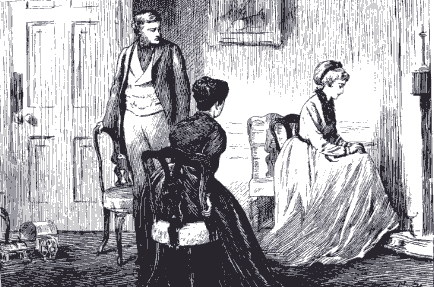

Marcus Stone, "’Am I to go? [back to the West Indies]," He Knew He Was Right

There again followed two sets of two panels run at the same time, with one panel directly after the other. The themes across both were class, gender, masculinity, race, ethnicity, and imperialism in Trollope’s fiction.

This time I chose the session which was about the lesser known short stories and novels. Dr Helen Blythe examined Trollope’s presentation of European colonizers who try to hold onto their Englishness or gentility. "Catherine Carmichael, or Three Years Running" (set in New Zealand) was her text. Holding onto genteel class ideals is seen by Trollope as central to their cherished identities and very survival. Catherine Carmichael endures brutal behavior from a husband who scoffs at such norms.

Dr Susan Shelangoskie presented a lucid thorough-going analysis of Trollope’s presentation of young women in a newly technological world which offered them independence through work. Trollope is for this as long as the work remains subordinate towards what is to be the young woman’s "real" goal: marriage to a man. She showed how the norms and customs used to control women in the home were transferred to work outside the home. Her texts were Trollope’s short story, "The Telegraph Girl" and non-fiction journalistic article, "The Young Women at the Telegraph Office".

G. H. Thomas, "She read the beginning—Dearest Grace", Breakfast Scene, The Last Chronicle of Barset

I found Dr Blythe’s analysis compelling and told her about the recent powerful Australian film, The Proposition where the goal English police officer (played by Ray Winstone) struggling to make a genteel life for himself and his wife (played by Emily Watson) in the bush in Australia, is much sympathized with, but shown to have a unrealistic if poignantly understandable goal. She is raped and he near murdered by the desperate bush rangers he must try to subdue. Dr Shelangoski’s paper was sensible, straightforward and accurate. I was glad she called attention to the little-known article, and she told me afterward that she had found my online bibliography for the short stories and etexts of non-fiction very helpful.

To be honest, as I was to give my paper within the next hour I was too nervous to listen closely to the third speaker.

Of the papers in the panel I didn’t hear, the one which had attracted me most (from the abstract) was an analysis by Prof. Mary Jean Corbett of the conflicts in identity Phineas Finn experienced (does he enact an Irishman really?) and the way readers have perceived Finn to be "too much like a woman." I now realize Prof Corbett discussed the intersection between Irish and English identities as they were seen stereotypically at the time1.

(From the abstract I had thought its phrases and thus paper referred to how Phineas might to conventional thinking appear to be weak because he is willing to change his mind (=womanish), especially since at the close of Phineas I, Phineas loses his battle to maintain his integrity and yet stay within Parliament. What attracts me to Phineas II is since he is Irish and Catholic but also a gentleman Phineas remains a half-outsider, a fringe person. Thus since most of the characters are indifferent to all but their own interests, Phineas becomes a target for radical distrust, is put on trial for murder, and experiences intense depression when his illusions about how his friends view him as one of them and as an honorable man, and about their capacity for loyal friendship, are shattered. To me Phineas’s sensitivity is central to the finest elements in his character and Trollope’s iconoclastic depiction of manliness in his heroes.)

I was the first speaker in one of the two second sets of panels, and have now put my paper online: Trollope’s Comfort Romances for Men: Heterosexual Male Heroism in his Work. Here is my central argument:

My argument is that Trollope’s most profound analyses of characters reside in his perceptive realistic depiction of male heterosexual patterns of sexuality as these conflict with the social customs of his age and ours. Drawing on his personal experience, Trollope justifies unheroic heroes and redefines worldly loss, defeat and individual withdrawals from social life and competition as misunderstood and understandable choices whose courage is underrated; through his presentation of heterosexual heroes Trollope defends his male readers against the norms he suffered from as a boy, young man, and as a older successful man too. There is much subversion here: very unusually Trollope gazes boldly on heroes who are not sexually and socially triumphant. He repeatedly presents the norms for such triumphs as oppressive, shallow, and even useless and counterproductive except when powerful characters instinctively admire them. He frequently sympathizes with males who regard the demand that they enact masculinity in dominating, aggressive, glamorous and overtly ranked-based ways as distasteful and against the grain of their character; they are unable or unwilling to articulate their point of view because they fear shaming and defeat. Their inability or refusal to manipulate these social codes disables them in the continual struggle for dominance against submission that Trollope depicts as also what shapes most human relationships. When their story is tightly interwoven with that of strong, passionate, frustrated or equally repressed, and obtuse and understandably vindictive women, they become crippled, paralyzed and tragic figures.

While I ranged across Trollope’s oeuvre in my opening few paragraphs and closing two, I focused in the center of the talk on Miss Mackenzie, Is He Popenjoy?, and Ayala’s Angel. In the last panel of the third day people were asked to answer the question why should we read Trollope today. My answer was:

In an era where we find ourselves in the midst of a re-masculinization of the norms of behavior and art in terms of a narrow macho male ideal, where not only a woman’s freedom to express her sexuality is contested, but a man’s is too, Trollope’s male romances provide a salutary alternative and ironic reading of heterosexual male personalities. Trollope has provided us with material capable of opening up our understanding of masculinity, manliness, and heroism so as to enable men’s lives to be less unhappy.

I was still too excited to listen to the second paper in my panel. I spent the time calming down. I did, though, listen to third presentation, Prof David Skilton’s talk. He argued that the way that the thought processes in making choices which Trollope endows women with allows modern readers to find in the women’s subjective life the same depth and richness of thought that we find in his men’s subjective life so that it does not matter if the women’s actual or literal choices for how they will spend their lives are severely limited.

I’m not sure I was persuaded that the literal limited choices can be overlooked just in favor of ethics and psychology as such, for the latter are dependent on experience hoped for as well as had. I’m also not sure that women’s thoughts processes are the same as men’s. However, he presented such good quotations from Trollope’s novels, and included some of the most fascinating characters like Mary, Lady Mason, the tragic heroine of Orley Farm, who forges a will in order to give her son a chance at gentlemenly status, and women of "action" like Lady Laura Kennedy (the Phineas books), and women making conflicted major life choices (e.g. Alice Vavasour from Can You Forgive Her?) and women carrying on a career next to their husband’s (Lady Glencora Palliser).

We all then broke for lunch. Quiche, sandwiches, fruit, coffee, juice and wine were on hand. We could eat at the large windows or outside on picnic tables. I much enjoyed mingling with the participants and talking to Nick, Clare, and Rob Polhemus for a while.

Again there were two sets of panels. This time I did not go to "Dissonant Feminities" but instead treated myself to Michael Brook’s witty talk, "Anthony Trollope: American Feminism, and the women on the New York City horse cars." Since I still mean to try to write a paper on Trollope’s North America, that being his text made his talk clearly useful for me. He divided the women Trollope encountered during his time in North America as women who challenged the system of separate spheres and women who didn’t, and said that while Trollope disagreed with the first group, he responded to them with a patient tone (and liked some of them very much); as to the second group, Trollope castigated these women when they were aggressive. He said Trollope did not like women to have separate spheres (like ladies’s drawing roolms) in public. These were invented for women to come out comfortably in public.

A good deal of Prof Brooks’ talk was about Kate Field and Trollope’s ambivalent and ambiguous love relationship with her. I’d like to read the biography of her life he mentioned and some of her writing. He also described some books by feminists which I’ll see if I can get hold of, e.g., Catherine Dall’s Women’s Right to Labor. Like Field (and Barbara Bodichon whose Women and Work I argued in my notes to my paper Trollope read), Dall argued women had a right to a career, to do useful work for a living wage. Prof Brooks said Trollope’s chapter on women in North America was partly meant as a refutation of Dall. In it Trollope insists "the best right a woman has is the right to a husband."

As I recall, Trollope said the woman question is about male power and to give women incomes and independence is to take power from men, i.e., jobs, money, control, the ability to dictate how their lives in private shall be led without having to shape themselves by a particular woman’s needs. His strongest point I thought was the one that if you allow women to work for money, soon men will refuse to support them or demand that they equally support the household. His weakest point is his basis: he insists on pretending that men do in fact support women willingly and stay married to them, and that men do in fact treat women well. In reality a large proportion of women spend their lives single and when you give people power most will take ruthless advantage of those they can control, and here we are talking about men’s control of women’s bodies.

A smaller point brought up in Prof Brooks’s talk: it is true that Trollope produces "astonishing diatribes" towards women who wear crinolines and demand equal literal space in public with men. When we read the text on Trollope-l and I studied it afterwards I became convinced that he deeply resented women behaving independently of men as if they were not beholden to men for not attacking them physically. He seemed to feel that "chivalry" was something men did by choice for women, and if women didn’t show gratitude, the men were justified in "returning" to making visible how brute power was the source of the social order which gave men control over women.

John Millais, "Waiting at the Railway Station," from Good Words

The other two papers I heard and the three in the other session were all feminist in outlook. Maia McAleavey, a doctoral candidate at Harvard, showed how Trollope’s request that the reader "love" Lily Dale revealed how he was imagining this reader to be a male who is erotically desirous of this imagined seductively sexually yielding victim-heroine. There was a paper by a DPhil student, Yvonne J. Huang, on Trollope’s hunting women and one by Prof ILana Blumberg about how Trollope presents female self-sacrifice as something they take pleasure in which gives them what they (really?) want: both papers were about 19th century women’s struggle for autonomy as mirrored in Trollope’s strongly masculinistic fiction. Prof Anca Vlasopolos focused on Trollope’s short story, "Mary Gresley" (as had Prof Polhemus) and Trollope’s novella, Sir Harry Hotspur: for her in the first we see the destruction of a young woman from the distanced approving perspective of an older man; in the second, the erasure of a young woman who devalues herself. The value of these for the modern reader is they allow us insight into Victorian gender politics.

Just on Sir Harry Hotspur I’ve always felt this sympathetic tragic romance (Trollope wants us to grieve over the heroine’s death) anticipates Henry James’s Washington Square. I prefer James’s story as it seems to me more truthful about how the relationship between parents and children are adversarial as well as supportive. Trollope buys into the myth of young female masochism before the sadistic rake male while James shows the cruelty and indifference of people (in this story just about everyone) and their willingness to bully and use the sensitive and good-hearted. I find it unbearably moving when Catherine Sloper turns her face to the wall and lives within and on herself rather than be hurt so radically again. Erasure in this James’ story is safety and peace. James’s heroine didn’t have to die but can live on in the minimal way described by Virginia Woolf at the close of A Room of One’s Own; alas, that she has lost all hope and will not create anything outside herself for she does not think anyone will appreciate or use it well. She does provide money and services for the poor.

When this last session was over, everyone trooped out to the front area where we had had lunch and there was tea and cakes and biscuits and cheese. To me it was too hot for tea and any sweets so I drank cool water. I talked with Nick and Clare for over half an hour and then Clare again drove me down the hill to the train station. I was very lucky as an air-conditioned long train (from London) had just driven up. I jumped inside.

Half an hour later Edward was walking on the beach just in front of the tower when I arrived. Since we had planned to do this (and had not bought anything to cook for supper), we went out to eat in one of the two good pubs (I liked the meal) and then went for another long stroll. We were back in our tower by 10 and asleep before the clock tolled 11.

Peters Tower, late evening, before sunset, high tide, Lympstone Village, Devonshire.

Back again on Monday night to tell of the last day,

Elinor

1 See Professor Corbett’s exposition in the comment section of this blog.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I’ve realized more these last two or three weeks that I get a lot from your writing, not just the intellectual discussion, which is always worthwhile, but even more so the energy and engaqement with which you address what you care about.

Kate Field had a strong personal relationship with Dickens, and it seems to some scholars, including me, that she hoped to have an affair with him. I’d like to read the biography of her you refer to.

It interests me that you met the very impressive Nick. Would you mind describing him a bit?

— bob Jul 30, 2:17pm # - The name of the biographer is Lilian Whiting and the book Kate Field: A Record. I've read Dickens and Collins went in for casual sexual encounters when in Paris, and both lived with women they weren’t married to; however, from what I’ve read of Dickens, I don’t see him going in for casual sex on a regular basis with so-called respectable women. I know very little about Kate Field beyond that she could write very superficially and Anthony Trollope was "in love with" her.

I would not describe someone in public the way you ask. Among the suggested rules of conduct on my lists I ask that people not talk about other people in front of them as if they weren’t there.

E.

— Elinor Jul 30, 8:26pm # - Dickens and Kate Field had a deep friendship of some duration, so had they had an affair it would not have been casual sex. It didn’t happen because he was involved at the time with Ellen Ternan, but otherwise it might have.

I agree it’d be inappropriate to report in a place like this on certain personal aspects of friends one knows or meets. But I thought there might be other qualities that might be noted, just to be pleasant. Nick is such a friendly guy that I’d like to be able to picture him a little.

— bob Jul 31, 10:21am # - You seem to know a whole lot about Kate Field :)

Do you have an opinion on whether she "hoped to have an affair with Anthony Trollope"? There are many entrenched stereotypes about him: he was a man who did have liaisons outside his marriage, and he was deeply in love with Kate Field.

Maybe I’ll buy that biography myself. Alas it’s probably one of these safe books which denies all sex activities unless there is an explicit record. It was written in 1899 though so has the merit of contemporaneity. And even today it’s the rare writer who reveals their inner life.

Trollope is very sceptical about how truthful any autobiography can ever be, and calls his own this "so-called autobiography."

Elinor

— Elinor Aug 1, 7:36am # - Googling, I find that Gary Schornhurst has a new biography of her that a year or two ago was "forthcoming," but I can’t find it anywhere. When I think more about KF and Dickens, I wonder if, even if he had been single, he would’ve wanted an affair with a strong woman like her.

— bob Aug 2, 12:07pm # - From Claire Tomalin’s biography of Ellen Ternan (and also Charles Dickens during the years he was basically living with Ternan on and off), I gather Ternan was a very strong woman. The man she married next she dominated. If she and Dickens hid their affair so hysterically, it seems it was not just a matter of his possibly losing the public adulation of fools and the conventional, and therefore lots of money, but their own overwrought attitudes towards sex.

This is born out by Dickens’s own portrayal of women (or lack of it) in his novels. He has saints and monsters or flat two-dimensional heroines.

About Kate Field’s attitudes I know nothing but she too would probably be careful to hide all affairs, and it would not be easy with the famous Dickens.

Elinor

— Elinor Aug 2, 9:11pm # - Prof Corbett wrote offblog to say:

"I just checked out your blog re the Trollope conference (via your VICTORIA post) and discovered that you were sorry to have missed my paper. Since you read only my abstract, which is quite different from the paper itself, I think you’ve no doubt got the wrong impression of what I actually wound up saying (I’ve pasted in that bit below).

“Two Identities”: Gender, Ethnicity,

and Phineas Finn

In the second volume of Phineas Finn (1869), Phineas secures a place in government upon the death of Lord Bosanquet, which elevates Mr. Mottram to the House of Lords:

“ … as he was Under-Secretary for the Colonies, and as the Under-Secretary must be in the Lower House, the vacancy must be filled up.” The heart of Phineas Finn at this moment was almost in his mouth…. But his great triumph soon received a check. “Mr. Mildmay has spoken to me on the subject,” continued the letter, “and informs me that he has offered the place at the colonies to his old supporter, Mr. Laurence Fitzgibbon.” Laurence Fitzgibbon! “I am inclined to think that he could not have done better, as Mr. Fitzgibbon has shown great zeal for his party. This will vacate the Irish seat at the Treasury Board, and I am commissioned by Mr. Mildmay to offer it to you’” (II, 43-44).

The narrator continues:“Phineas was himself surprised to find that his first feeling on reading this letter was one of dissatisfaction…. Had the new Under-Secretary been a man whom he had not known, whom he had not learned to look down upon as inferior to himself, he would not have minded it…. But Laurence Fitzgibbon was such a poor creature, that the idea of filling a place from which Laurence had risen was distasteful to him” (II, 44).

Laurence Fitzgibbon rises, as Phineas reflects, from “‘favour and convenience … without any reference to the service’” (II, 44); Laurence Fitzgibbon rises without a shilling to his name, as Phineas has learned to his own chagrin; Laurence Fitzgibbon rises despite being, as Jane Elizabeth Dougherty notes (140), the most stagy of stage Irishmen in Trollope’s English fiction. Phineas’ own “mastery of standard English forms” (McCourt 53) may be an asset, but Laurence Fitzgibbon’s brogue does not prohibit his advancing to a salaried post of £2000 a year.

Most of all, Laurence Fitzgibbon rises owing to his “‘great zeal for his party’”; but he falls four short chapters later, “having by mischance been called upon for some official statement during an unfortunate period of absence” (II, 80), because he will not do his work. “‘Nothing on earth would induce him to look at a paper during all those weeks he was at the Colonial Office’” (II, 100), as Barrington Erle confides to Phineas, who thus becomes an Under-Secretary for the Colonies after all. Phineas attacks his new job with the “great zeal” Laurence reserves for politicking and, presumably, gaming: although “his back was broken” from Violet Effingham’s refusal, he prepares for a meeting with Lord Cantrip and Mr. Gresham, “determined that “as long as he took the public pay, he would earn it” (II, 143). Like any subordinate, Phineas’ primary job is to make his boss look good to his boss: “he left it to Lord Cantrip to explain most of the proposed arrangements,—speaking only a word or two here and there as occasion required. But he was aware that he had so far recovered” from his broken back “as to be able to save himself from losing ground” (II, 143). And his efforts meet with praise of a particular kind: “‘He’s about the first Irishman we’ve had that has been worth his salt,’ said Mr. Gresham to his colleague afterwards. ‘That other Irishman was a terrible fellow,’ said Lord Cantrip, shaking his head” (II, 144). Like Phineas, Gresham and Cantrip have “learned to look down upon” Laurence Fitzgibbon “as inferior to [Finn] himself,” to see one Irishman as better than another, with their favorite preferred for his superior industry, his devotion to his work, his willingness not just to collect but to earn “the public pay.”

Interestingly, Laurence Fitzgibbon also articulates Phineas’s value in these terms. When the party men gather at the opening of Phineas Redux (1874) to choose candidates who will help them to take back the “Whitehall cake” (PR 10) from Daubeny and the Conservatives, some of those that Finn left behind on his return to Ireland are still singing his praises:“He’s the best Irishman we ever got hold of,” said Barrington Erle—“present company always excepted, Laurence.” “Bedad, you needn’t except me, Barrington. I know what a man’s made of, and what a man can do. And I know what he can’t do. I’m not bad at the outside skirmishing. I’m worth me salt. I say that with a just reliance on me own powers. But Phinny is a different sort of man. Phinny can stick to a desk from twelve to seven, and wish to come back again after dinner” (PR 12-13).

Where Barrington Erle pronounces the ethnic superlative, Laurence neither surrenders his own claims to efficacy nor makes the ethnic distinction that all the Englishmen make: “‘a different sort of man’” from me, not necessarily a better or worse man, but different from me in his possession of different “powers”—close application, industry, commitment.

I am belaboring the opposition between these two figures of Irish masculinity at some length in order to contest the claim made by Nicholas Dames that “Phineas’s career sequence obscures … any element of ethnic or class conflict”: “his Irishness, or his class status as son of a country doctor, is strangely washed out compared to the vividness of his vertical ascension…. the narrative emphasis upon the individual’s upward progression obscures the larger class or ethnic trajectories that may be in play” (260). I’m broadly sympathetic with Dames’ approach to “the career,” and particularly to his point that “‘the colonies,’ as an avenue of professional advancement, signifies in Trollope a necessary specialization”—like Palliser’s passion for the decimal coinage—“that mitigates against any more all-encompassing ambition” (268). But it’s not quite right to say that class and ethnicity are “washed out” in Phineas Finn. Clearly, Trollope makes some strategic choices, and one of them lies in departing from explicit stereotypes of Irishness in the representation of his central character and his plot(s). As one of Phinny’s many foils, Laurence Fitzgibbon is a feckless, improvident, “youngest son” (I, 3) of an Irish lord, a good fictional example of what the Irish historian Roy Foster calls “micks on the make”—and isn’t there a pun even in his name? Fitzgibbon bears the dubious distinction of being to his political superiors (and even to Finn himself) that “other Irishman,” “a terrible fellow” from the administrative point of view, so that our hero need not be tarred with that particular brush.

To begin to understand the “class and ethnic trajectories” in play here, I am suggesting, requires an initial recognition that Trollope does not construct Irishness exclusively in opposition to Englishness. As John McCourt has established, Phineas’ Irishness is not signified, as Fitzgibbon’s is, through the stereotyped conventions of Irish speech, phenotype, or even conduct. As the son of a professional rather than a landlord, associated with the Catholic middlings rather than the Anglo-Irish gentry, Phineas decidedly belongs to the stratum to which Trollope, in the years after the famine (which Phineas and his family must have lived through), assigned some of the modernizing powers of progress. The difference between the careers of the two Irishmen is thus given moral and ideological weight over the course of the novel. Phineas, like Laurence, gets his start as a junior lord by filling “the Irish seat at the Treasury Board,” for which their national origins presumably qualify them both. But having “achieved his declared object in getting into place,” Phineas “felt that he was almost constrained to adopt the views of others, let them be what they might” (II, 163)—a conscientious qualm to which Laurence is never apparently subject. Phineas resigns his position as Under-Secretary for the Colonies so as to be able to support the legislation for Irish tenant right to which he commits himself on his Irish tour with Mr. Monk, legislation that would (and did, in 1870) give Irish tenants security for improvements they made to their land holdings. Here Trollope makes Phineas’ Irishness matter, as he gives up his post and thus his seat on a point of equity and fairness: “his Irish birth and Irish connection had brought this misfortune of his country so closely home to him that he had found the task of extricating himself from it to be impossible” (II, 330). Having failed to accept “that as he had made up his mind to be a servant of the public in Parliament, he must abandon all idea of independent action” (II, 179), Phineas in the end chooses “independent action” on behalf of Ireland rather than what Mr. Low calls “‘slavery and degradation’” (I, 46).

In this choice, Phineas conforms not just to conscience or patriotism, but to the ideal and ideology of manliness, a construction that exerts some considerable sway over Trollope’s characterization of “the Irish member.” In A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England, the historian John Tosh defines “manliness” as an internal state made evident in outward display: “Sometimes there was an implied claim to natural endowment; more often a manly bearing was taken to be the outcome of self-improvement and self-discipline. This aspect was explicit in what was for the Victorians the key attribute of manliness— independence” (111) of thought, speech, and conduct. “The manly man,” as Tosh writes in his recent collection of essays, “was someone who paid more attention to the promptings of his inner self than to the dictates of social expectation” (“Gentlemanly” 87), with the opposition between the two something that Tosh and his sources take as a given. And in politics, a man’s attention to said promptings would ideally issue in “a rejection of all forms of patronage,” the dependency that would vitiate “autonomy of action and opinion” (“Middle-Class” 111). Tosh argues that “manly independence” constituted “a vital prerequisite” for, rather than being an effect of, “responsible political agency” (“Gentlemanly” 96), which seems true enough in the context of the 1860s, as English workers (and some women) agitated for the extension of the franchise in the face of elite anxiety about their ability properly to use it, while Fenian activism only confirmed in some English eyes an Irish insufficiency for exercising political autonomy. Yet in distinguishing “manliness” from “gentlemanliness,” associating the latter with “exclusiveness and affluence” and characterizing the former as “open and unhierarchical,” Tosh suggests that the manly ideal was accessible to a broader range of Victorian men: “birth, breeding and education were secondary, compared with the moral qualities which marked the truly manly character” (“Gentlemanly” 86). Is it open to some Irishmen, too? Or is it ethnically and racially specific?

If the ideal was represented as democratically open, then it also generated particular exclusions and depended on particular oppositions: it’s easy to see, for example, that “manly independence” implied, indeed “was premised on,” as Tosh writes, “a powerful sense of the feminine ‘other’” (“Gentlemanly” 91), the “womanly dependence” emphatically represented in the Phineas novels by Robert Kennedy’s recurrent references to his wife as “‘bone of my bone, and flesh of my flesh’” (e.g., PR 86). With Tosh limiting the scope of his study to Englishness, it’s difficult not to wonder how taking notice of a persistently feminized and racialized Catholic Irishness within mid-Victorian culture might complicate his picture. Yet in relation to the distinction that I have noted in Phineas Finn, where Fitzgibbon embodies the stereotypical ethnic elements of Irishness, the claims of “the Irish member” to manliness and independence, in Tosh’s terms, look pretty strong.

What’s important to remember is precisely the relational character of a category like manliness and a quality like independence, the variations they undergo when you shift the context. Phineas looks independent, for example, in choosing to support Mr. Monk in the debate over tenant right, by contrast not just with Fitzgibbon, but also with Ratler, Bonteen, or Erle, the whole pack of functionaries for whom the concept of voting against the party is anathema because keeping power and place is the supreme goal. (It’s not voting with them that elicits feminizing rhetoric: as Bonteen says to Ratler to provoke Phineas, “‘I’ll bet you a sovereign Finn votes with us yet. There’s nothing like being a little coy to set off a girl’s charms’” [II, 296]). He also looks a good deal more independent by the side of Lady Laura Kennedy, “who from her earliest years of girlish womanhood had resolved that she would use the world as men use it, and not as women do” (II, 10-11), and lives to regret the choices she made. Trollope indeed supports an ideal of “manly independence,” against which he measures Finn and other characters (including some female ones), but he persistently figures that ideal for conduct within the contexts of class and gender privilege, ethnic and national character. Thus when John McCourt argues that “Phineas has neither the political nor financial resources to be independent of the men who put him into parliament,” I agree; but when he goes on to claim that Phineas “suffers this dependency which is surely metonymic of Ireland’s more general dependency on English favours” (55), I must disagree. If Phineas is “dependent” in some contexts, and is thus represented or understood as “effeminate” or “feminized,” then in the specifically Irish dimension of his political identity, he is very much the manly man, in rejecting the patronage that got him his place because it impedes his “autonomy of action and opinion.” He is freer as an individual than the nation whose collective interests he indirectly represents, and Trollope emphasizes this in making his Irishness most evident in the actions that send him back to Ireland at the end of Phineas Finn.

Issues of “manly independence” are also at play in how Trollope represents Phineas’ relationship to his girl back home, which waxes and wanes according to his English romantic and political fortunes. From the outset, Phineas exploits the distance between an Irish “here” and an English “there”: he appears differently to others, and to himself, depending on the location he occupies. Each time he returns to Ireland in Phineas Finn, usually at the end of the parliamentary session, he does so having spent a good part of the previous six or nine months pursuing an Englishwoman, during which time he has given the Irish “there” nary a thought. Already rejected by Lady Laura, he nonetheless tells Mary Flood Jones “‘how often’” he’s thought of her, committing one of those “perjuries” that “can hardly be avoided altogether in the difficult circumstances of a successful gentleman’s life. Phineas was a traitor, of course, but he was almost forced to be a traitor, by the simple fact that Lady Laura Standish was in London, and Mary Flood Jones in Killaloe” (I, 145). Rejected for the first time by Violet Effingham after the end of the next parliamentary session, he goes to Killaloe to find that Mary and her mother have decamped to Floodsborough “because it was thought that he had ill-treated the lady” (I, 328-29). If the narrator has previously called him “a traitor” with some mild irony on the nature of a “gentleman’s life,” on this occasion he makes no judgment, but gives us Phineas’s thoughts instead: “Now that he was in Ireland, he thought that he did love dear Mary very dearly. He felt that he had two identities,—that he was, as it were, two separate persons,—and that he could, without any real faithlessness, be very much in love with Violet Effingham in his position of man of fashion and member of Parliament in England, and also warmly attached to dear little Mary Flood Jones as an Irishman of Killaloe” (I, 330). Phineas here settles upon a fiction less troubling to his own sense of honor than the narrator’s charge of perjury and treachery through the conceit of the “two identities,” in which potential “faithlessness” is rewritten in accord with the distance between there and here, his English career in London and his position as “Irishman of Killaloe.” And at this point in the novel, it’s the first identity he most wants to maintain: being “constant to Miss Effingham” (I, 145) would mean achieving the “politico-social success” (I, 143) in England that an alliance with her would guarantee, by which he would gain “Violet’s hand for his own comfort, and Violet’s fortune to support his position” (II, 131). And for as long as this is on the cards, being “an Irishman of Killaloe” will take second place.

What begins as a sort of comic Bunburying, from the narrator’s point of view, takes a more serious turn in the second volume, as Mr. Low’s early response to Finn’s decision to pursue a parliamentary career—there is “‘nothing in it that can satisfy any manly heart’” (I, 46)—looks more and more like a fair prediction. When Phineas goes back to Ireland to stand for the seat at Loughshane, the narrator comments on the danger to his character: “Perhaps there is no position more perilous to a man’s honesty than that in which Phineas now found himself;—that, namely of knowing himself to be quite loved by a girl whom he almost loves himself…. Phineas was not in love with Mary Flood Jones,” but “he would have liked to have an episode,—and did, at the moment, think that it might be possible to have one life in London and another life altogether different at Killaloe” (II, 107). With Mary clearly available and Violet still possibly so, the distance between the two locations widens: potential success with Violet seems to enable the fiction of “two identities,” or the double life, to persist. On his next visit to Killaloe with Mr. Monk, however, when he knows for certain “that all hope was over” of ever marrying Violet and “was in want of the comfort of feminine sympathy,” “Mary had kept aloof from him”: and “as a natural consequence of this, Phineas was more in love with her than ever” (II, 261). Putting emotional distance between them, Mary incites desire. When he returns from the tour, having “pledged himself” (II, 263) to tenant-right and knowing that he and Monk “must give up the places which they held under the Crown” (II, 264), he pledges himself to Mary as well.

For Phineas, independence in political matters means loss of independence in financial ones: neither a pledge to Ireland nor a pledge to Mary corresponds with the material, economic independence necessary to heterosexual manliness. Women in the novel know this well. When Mary Flood Jones tells her future mother-in-law “that it was quite possible that Phineas would be called upon to resign,” so “‘that he may maintain his independence,’” “‘Fiddlestick!’ said Mrs. Finn. ‘How is he to maintain you, or himself either, if he goes on in that way?’” (II, 276). Moving from this conversation in Killaloe to a London drawing-room in the space of a single paragraph, Madame Max tells Phineas that “‘a poor fellow need not be a poor fellow unless he likes’” (II, 276), holding out another hand and another fortune that would make him financially and thus politically independent by means of marriage. The terms in which Phineas contemplates her offer suggests the mix of materialist and psychic motivations that underpin his fantasy of total success:Immediately after this Phineas left her, and as he went along the street he began to question himself whether the prospects of his own darling Mary were at all endangered by his visits to Park Lane; and to reflect what sort of a blackguard he would be,—a blackguard of how deep a dye,—were he to desert Mary and marry Madame Max Goesler. Then he also asked himself as to the nature and quality of his own political honesty if he were to abandon Mary in order that he might maintain his parliamentary independence. After all, if it should ever come to pass that his biography should be written, his biographer would say very much more about the manner in which he kept his seat in Parliament than of the manner in which he kept his engagement with Miss Mary Flood Jones. Half a dozen people who knew him and her might think ill of him for his conduct to Mary, but the world would not condemn him! And when he thundered forth his Liberal eloquence from below the gangway as an independent member, having the fortune of his charming wife to back him, giving excellent dinners at the same time in Park Lane, would not the world praise him very loudly? (II, 276-77)

It’s not only amusing but significant that Phineas imagines a biographer who, much like Trollope himself in An Autobiography (1883), will subordinate “the little details of my private life” and write instead of “what I, and perhaps others round me, have done in” public and professional matters, “of my failures and successes such as they have been, and their causes” (1). And it’s significant, too, that because the distance between an English “here” and an Irish “there” has enabled Phineas not just to think of his engagement to Mary as “a thing quite apart and separate from his life in England” (II, 271), but to keep it entirely private, the fiction of “two identities” proves to have some currency after all, for “the world” certainly “would not condemn him” for his “faithlessness” if “the world” effectively knew nothing at all about it. To break his vow to Mary would be bad, very bad, certainly an ungentlemanly thing to do, but a thing that, like the engagement itself, could be kept hidden; if he could do it, and by marrying Madame Max both “maintain his parliamentary independence” and affirm “the nature and quality of his own political honesty,” Phineas could “[thunder] forth his Liberal eloquence” without stint.

The dicey term “eloquence,” associated with Turnbull and Daubeny, should give us some pause. As part of a rhetoric of display—what one puts on for “the world,” a little like “excellent dinners”—fine words are opposed to manly speech; ultimately, Trollope frames the desire to look well and to have a reputation, to be a public figure constituted for, even by others, as the end to be avoided, both by Phineas and by Madame Max herself, who turns down the Duke of Omnium just a few chapters before Phineas turns her down. Standing in Madame Max’s elegantly appointed drawing room, Phineas thinks, “What would such a life as his want, if graced by such a companion,—such a life as his might be, if the means which were hers were at his command? It would want one thing, he thought,—the self-respect which he would lose if he were false to the girl who was trusting him with such sweet trust at home in Ireland” (II, 314). “The promptings of his inner self” win out over “the dictates of social expectation.”

In this way, I think, Trollope represents a “manly” Irish subject whose affirmation of Irish choices constitute an effort to consolidate an independent Irish identity, which yet contains elements or traces of the gendered and racialized discourse of dependence that it disavows. Undercut by Trollope’s subsequent claim that “to take him from Ireland” was “a blunder” and that he was “wrong to marry him to a simple pretty Irish girl” (Autobiography 318), the characterization is yet significant as a particular moment in the broader literary history of Trollope’s relationship to Ireland, intervening as it does in what would become an increasingly polarized debate on English-Irish relations after 1870, a debate in which Trollope himself, as in the unfinished Landleaguers (1883), would take a far more hostile view of Irish members.

Works Cited

Dames, Nicholas. “Trollope and the Career: Vocational Trajectories and the Management of Ambition.” Victorian Studies 45 (Winter 2003): 247-278.

Dougherty, Jane Elizabeth. “An Angel in the House: The Act of Union and Anthony Trollope’s Irish Hero.” Victorian Literature and Culture 32 (2004): 133-45.

Foster, R. F. “Marginal Men and Micks on the Make: The Uses of Irish Exile, c. 1840-1922.” Paddy & Mr Punch: Connections in Irish and English History. London: Penguin, 1995. 281-305.

McCourt, John. “Domesticating the Other: Phineas Finn, Trollope’s Patriotic Irishman.” Rivista di Studi Vittoriani 6 (2001): 39-63.

Tosh, John. “Gentlemanly Politeness and Manly Simplicity in Victorian England.” Manliness and Masculinities in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Essays on Gender, Family and Empire. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2005. 83-102.

___. A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999.

___. “Middle-Class Masculinities in the Era of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1860-1914.” In Manliness and Masculinities 103-125.

Trollope, Anthony. An Autobiography. 1883. Ed. Michael Sadleir and Frederick Page. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

___. Phineas Finn: The Irish Member. 1869. Ed. Jacques Berthoud. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

___. Phineas Redux. 1874. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

— Elinor Aug 2, 11:13pm # - I asked Nick what "Bunburying" meant and he replied:

"Very quickly Bunburying is from Wilde's Importance of Being Earnest. Bunbury is an imaginary friend whom the hero (or protagonist) uses to escape social obligations which he wishes to avoid. It has come to have a meaning associated with sexual duplicity I think – I am not sure this is present in the play (I am not an enormous Wilde fan so my recollectioni s hazy).

Nick"

— Elinor Aug 3, 7:50pm # - Because my wife just last month directed a production of "Earnest," I happen to know that Bunburying is generally thought to be Wilde’s reference to secret homosexual relationships carried on while leading a straight life. As to your point about Ellen Ternan being a strong woman: undoubtedly she became that. But she began her affair with Dickens when she was virtually a child, in fact, his daughter’s age. It was a forbidden relationship for him on several scores—and very exciting and romantic for that reason—while an affair with Kate Field would’ve been with someone much more his equal, not only in age and culture but also in the kind of strength that comes with personal development. It would’ve been good for him to finally have such an experience, but I wonder if he’d have wanted to.

— bob Aug 4, 5:03pm # - So then the paper on Phineas Finn was using the term somewhat inaccurately. Nick suggested that and said "given its origin ‘comic Bunburying’ is tautologous (dear me I sound pedantic! :))." Jim suggested the equivalent of Bunburying can also be when students tell me their grandparent is dying and they must go hold his hand at the hospital. This sort of lying appalls me.

I told Nick (Jim would know this if he had been there and listened) the stance of numbers of the papers I heard on Trollope were alien to me. Why?

Despite the overt post-colonialism and other similar points of view many readers of Trollope (academic and non-academic like) do not identify with the underdogs and do not like Trollope’s characters for their continual subversion. These readers appear not to notice this, or if they do, and the character is a woman, inveigh against it. I've read people on lists ridicule Trollope's males or talk of how these characters "annoy" them.

I love Phineas Redux for Trollope’s depiction of Phineas’s depression and shattered state and for his explanation (justification for why he was so depressed). The horrible way Phineas was dropped by his so-called friends is made the novel's focus. It's why Trollope has him accused of the crime. But many readers appear to like Phineas for his great networking (instinctive pleasantness is the way Trollope presents this) and buy intoc onventional views of success and manliness.

On another panel, one ostensibly feminist, one woman speaker during question time after the papers were done just about burst out to say how she worried lest her daughter not marry someone presentable who would make money. I suppose what else could you expect from someone acting out a successful bourgeois career

How often a philistine point of view (or self-interested socializing one) comes out from people reading Trollope. Alas, he allows for it, does not overtly critique it, even justifies it. Trollope likes to argue on behalf of density and deliberately presents highly limited (semi-stupid) characters who have much power. It's called realism.

I really did think Polhemus’s paper was one of the very best, and Markwick’s worth listening to as revolutionary. Whether she will make a difference in Trollope studies will be interesting to see. Of course to do that she’s got to have a book and it’s got to appear in a "respected" venue (Ashgate is).

For what it’s worth I think Trollope had a few such relationships, and they were sexually consummated. One is strongly hinted at in The West Indies and the Spanish Main. It didn’t change his personality nor would it have Dickens. The attitude towards women in the period really marginalized them as effective presences with significant ideas. Mill was rare for seeing them otherwise.

And today it’s not much different. A woman’s body is what most men value her for. As to Bob's comments on Dickens and Field and possible sex: exciting and romantic ? What rot and rubbish. This is woman as "other," as the "dark continent."

You should read Tomalin's book for a glimpse of Dickens and Ternan. Ternan was also a real reader, an intelligent creative actress and later tried to build a better life for herself with a school. She couldn't as she didn't have the connections or prestige and her husband didn't know how to manipulate his. That makes me sympathize with him, but he also was under her thumb so he is finally pathetic. I do give him the respect of not believing he thought her 13 years younger and never asked about her past life.

Perhaps Bob it's you who are wanting to go to bed with Kate Field? having dreams about her?

Elinor

— Elinor Aug 4, 10:17pm # - I sent George Landow my paper to put on Victorian Web, and he wrote me about it:

"Thanks for sharing your excellent essay with readers of the Victorian Web! It has filled, or at least begun to fill, a need on the site for significant material on masculinity and permitted me to create a gender matters sitemap in the Trollope section. You’re up at http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/trollope/moody2/comfort.html

When your essay enters the VW or similar site, however, it becomes part of a network, and individual notes become, whether one likes it or not, separate nodes or documents in that network. What this means in practice is that some notes that might originally have served as minor comments to a much more important argument (such as your notes on manliness in Trollope’s heroines or Trollope’s non-traditional heroes) become valuable documents in their own right and as such (1) need their own titles and (2) may bring readers to your main argument rather than the other way around, and (3) often need or at least permit considerable expansion. Feel free to suggest new titles for the lexias made out of notes and to add any material you wish. E-text is both like velcro — things keep sticking to it — and always unfinished because always easily changeable …

As someone who’s been at this game for more than 4 decades, I have some criticisms and suggestions about both the html and your generally excellent writing. But I won’t bother you with them unless you’d like to receive them.

Thanks for thinking of VW!

Cheers,

George"

— Elinor Aug 10, 11:34pm #

commenting closed for this article