Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Pallisers 1:2: How can people fulfill themselves? · 2 September 07

Dear Harriet,

Well, finally I’ve watched the whole of Volume I, Part 2 of the 1974 BBC 26 part film cycle, the Pallisers. I copied down every word of the screenplay and took snapshots of the scenes (stills). Then I reread my transcription of Pallisers 1:1 and this new transcription and my first three blogs so am ready to try another summary and commentary.

Volume I, Part 2, is a remarkably full and rich part. I feel it may be summed up as asking a philosophical as well as social question: how can people fulfill themselves given their option; or, to put it another way, the imagined communities they must survive in? In the fifth episode of this part (“A New Candidate”), when Plantagenet Palliser (Philip Latham) asks the grieving frustrated Lady Glencora (Susan Hampshire), what is the matter, she replies, “I feel so empty.” She can think of nothing, has been given nothing meaningful to do. Unlike John Grey (Bernard Brown) reading will not fulfill her; socializing seems hollow (as yet), politics as her husband professes it a veneer; she would like a child, but none is coming. What then? Run away with Burgo Fitzgerald (Barry Justice)? For what? To what? As she will learn, her friendship with Alice Vavasour (Caroline Mortimer) has its limits. I agree with Stanley Cavell in his books on film (Pursuits of Happiness, Contesting Tears) that films have become a serious art form which pose important questions about what can of life people might want to live.

As I wrote, 1:1, is about a coerced match: we see Plantagenet Palliser separated from Griselda Grantley, Lady Dumbello (Rachel Herbert), and Lady Glencora McClusky separated from Burgo Fitzgerald; the two principals are presented as at least (in Lady Glen’s case) sincerely in love or (Palliser) potentially capable of depths of feeling and loyalty; he is genuinely devoted to an ideal of public service; she fears Burgo Fitzgerald will destroy her somehow but when she gives herself over to Palliser it’s because she’s forced; she does not want or love or understand or sympathize in the least with him, but she does gather he is decent, stable, kind, and in the moment of accepting his ring, she turns a vulnerable open trusting and puzzled face to his (what is this life about?), and he pities her.

Volume 1, Part 2, changes the parallel to the one we find in Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her?. Alice Vavasour has refused to help Lady Glen meet Burgo clandestinely partly because she is conventional and partly because she herself has been so burned by George Vavasour (Gary Watson) whose promiscuous sexual appetites and exploitative ways she found degrading. Nonetheless, she has not alienated Lady Glen. Lady Glen trusts Alice as an honest deeply feeling woman who can aid her in her trouble, give her strength, and console her because they can talk candidly.

Alice’s situation is made to parallel Lady Glen: John Grey is even a noble man who is loving, good and kind, but dominating, and wants to pull Alice wholly into his life’s needs, to serve his desires which he nonetheless thinks will serve hers; as Lady Glen is drawn to Burgo, so Alice is drawn to the excitement of George’s career; she would like to stay in London (not go live in Ely); as in Trollope, Alice’s sexual attraction to George is ambivalent; she’s attracted but also finds herself repulsed. Burgo and George pursue both women; in effect, they stalk them, George with the help of his loving sister, Kate (who betrays Alice this way and played by Karin MacCarthy), and Burgo with the help of George (and his money).

However, as we move further into Part 2 and reach Matching Priory (the second scene of Episode 9 titled “Glencora Adjusts”), we resume a thread partly adumbrated in the Volume I, Part I, when Plantagenet is pictured as reading blue books and unable to socialize frivolously: he has an ideology he cares seriously for, and a purpose (however mocked): to rationalize the English money system. He can find meaningful activity for his life in politics.

In Episode 9 (“Lady Glencora Adjusts”), scene 2, Lady Glencora is making a list of guests to invite and thinking about where she wants to put them, and Plantagenet comes into the room she’s in with Mr Bott (John Stratton); Palliser and Bott have been planning strategy for the coming session; Palliser longs to be made Chancellor of the Exechequer. At this point the scenes dramatizing political realities and behaviors begin to multiply and are brilliant; they parallel the scenes about love and marriage.

Again we see money is the most important element to everyone (getting as much of it as possible), that the way to succeed is through being accepted into a clique whose criteria for acceptance is the social acceptability of your behavior and status (not your political ideals or the morality of your previous acts). This acceptance is achieved through maneuvring, manipulation, and the sheer press of one personality upon another where one wins out over the other, sometimes unexpectedly because some trait emerges which takes over. One can win out by sheer determination & luck, a kind of desperate desire (embodied in the end of the part by Burgo Fitzgerald’s hope as he longs with a crazed intensity for Lady Glen, and at that point only secondarily for her money). One retreat (as Alice’s father, John Vavasour, played by John Glyn Jones, practices as well as John Grey). One can get it simply through place, position, wealth and power and hard work at the right moment at the right time (as Palliser has once he marries Lady Glen).

And there are yet other ways we see dramatized. The greatness of the last scenes of this part’s concluding episodes is they epitomize what people really would do in an imagined situation suggestively enough to present a complex believable portrait of the way politics worked in the 19th century and still in part do.

To return to Volume One, Part One: the penultimate scene is the strikingly expressionist scene of Plantagenet walking in wood with his uncle to a central open area to which Lady Glen walks with two aunts. The uncle and aunts enact the part of cruel fate or the force of aggrandizing conformity (amoral, since both aunts and uncle hint to Lady Glen and Plantagenet that after marriage they may do as they wish with the partners they really love), and the two central protagonists enact the sacrifice to this corrupt social order—and gain economic safety and social acceptance (Lady Glen) and convenience, power, and comfort, (Plantagenet, if Lady Glen will only cooperate, or obey him).

Part Two opens in a grandiose wedding at Westminster. Throughout the whole of it neither bride or groom looks at one another. It is superlatively well acted by both: his quiet grimness and her intense reluctance and then half-hysterical automatic obedience. I find this still where we see their mutual if diversely striken looks made plain particularly moving:

The altar dissolves into a still of a large clock above a rich mantelpiece in a gentleman’s club. Burgo and George sit nearby drinking. Burgo’s look is of someone who has had something central to his existence permanently stolen from him and he cannot retrieve it—ever. He could not look more frozen were Lady Glen to have died:

We then switch to the couple on honeymoon. Plantangenet and Lady Glencora are in a sled moving across a snow-bound landscape: Switzerland. Their conversation reveals they are instinctively incompatible as personalities and yet anticipates one part of their adjustment as seen in Trollope’s novels: he controlling himself and keeping to common sense; she needling him but only so far; it’s funny. I was struck by how she carries a doll (I know Renaissance women did) and how towards the end he tenderly covers her with a blanket. In the penultimate part of the series (Volume 3, Part 25), now Duke of Omnium, he will again covers his Cora with his cape when they are in the ruined priory on a cold night, but she already had the cold which will turn into pneumonia and kill her when still in her forties.

There are many effective stills of Switzerland (or a snow-filled landscape photos) throughout the Part. These are appropriate. With their repose and quiet stillness they counter the human worlds of intense and messy emotions we continually encounter.

Out first still followed by one of the carriage or sleigh with Plantagenet and Lady Glencora Palliser in it:

Alice Vavasour is reintroduced waiting with her father for Kate to arrive so they can begin their parallel trip to Switzerland. George comes with Kate, and thus begins the unfolding of the primary story matter in Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her?. In the first five films of the Palliser films Alice and George’s story forms the secondary parallel story. Raven also draws his matter and characters from Trollope’s Dr Thorne (a visit Frank Gresham makes to Gatherum Castle owned by the Duke), The Small House of Allington (the initiating love stories); and with some of the politicians who first appear in Phineas Finn, e.g. Moray Watson as Barrington Erle, and the roue-rake-choral figure, Donald Pickering as Dolly Longestaffe from The Way We Live Now and The Duke’s Children. It’s important to see how from the very beginning of this story matter Raven has transformed matter from across Trollope’s corpus to embody his own vision of human relationships as well (probably) as please a conventional TV audience.

For example, In Trollope, Alice Vavasour’s father is someone who has abdicated his responsibility; he never keeps his daughter company; he pays no attention to her life, gives her no advice, just about shows no interest in her until it seems she is risking losing her money by re-engaging herself to George Vavasour. She is thus not only endangering herself bodily as well as emotionally, but risking part of the sum upon which he and her comfortable life in a rich (if ugly) flat in London is based. In Trollope’s novel, John Vavasour does not go to Switzerland with his daughter and Kate, thus leaving the way open for George to fill the part of a male escort and set all the terms of the discussion they have.

In Raven’s film, John Vavasour (John Glyn Jones) is a kindly comic figure who cares about his daughter but does not have adequate weapons to control her: as she controls her own money, inherited from her mother—the point is emphasized in the film by mentioning it; it’s really de-emphasized in the book). In this filmic Part and all the subsequent ones John Vavasour is a marginal but importantly caring presence. In Raven’s film he is right there on the terrace of the hotel in Switzerland trying to shoo George away, reminding Alice firmly of how George betrayed her. Alice’s father is there with Alice when she visits John Grey in Ely, jokingly urging her to accept Grey as a good if apparently dull man is a wiser choice for a husband than a bad and cruel one:

“Ah, just a little too much on the good side; still, that’s better than the other thing.”

I note that in the film a desire for a peaceful life and spending time in writing scholarly papers of great integrity is equated with dullness by all but Plantagenet Palliser—who recognizes himself in Grey and had read and enjoyed said papers; yet all the scenes with Grey thus far are pictorially appealing.

They talk with open faces to one another

The lovely room with its effective browns and reds. He wants her to choose a fabric.

Throughout the last and this part Raven makes George much more likeable than Trollope ever does. Raven presents George (and Gary Watson enacts the character with boyish gestures at moments) so as to make us sympathize very much with him. Trollope’s seething murderer with a dark gashed scare across his face (a kind of symbol of his instinctive hatreds) is erased and we find ourselves with a (thus far) well-meaning if adventurous and none too scrupulous ambitious man. In one of the most memorable and effective scenes in Volume 1, Part 2 (Episode 10, “A New Candidate”), we watch the pubowner Mr. Grimes (James Berwick) and the lawyer-campaign manager, Mr Scruby (Gordon Gostelow) fleece George first for a whole tray of beer for Grimes’s customers, and then wrench from George 1000 pounds in bills for the coming campaign. And this is just a start.

Grimes at the tap (our first view of him)

Mr Grimes (James Berwick), Mr Scruby (Gordon Gostelow) and George Vavasour (Gary Watson) in backroom of Grimes’s pub, they hovering near to grasp that money from him

We are to feel for George, not see him as a knave trying to get into where he doesn’t belong (as in the end of Can You Forgive Her? he is judged), but as a sympathetic helpless dupe. Not for him the rich mansion of Matching Priory supported by genuinely pro-labor, Mr Bott, who is a docile sycophant, and noble characters whose names we hear mentioned (the Duke of St Bungay is mentioned but does not yet appear); he must fight through with hard mean crooks to get past the Parliamentary door.

The continuous story centers on Lady Glen and her puzzled lonely anguish. Slowly studied, this second part reveals why Raven said the chief character of the 26 episodes is Lady Glencora Palliser. Among the important statements Michael Barber reports of Raven’s attitude towards this film adaptation (in Barber’s biography, The Captain), is that Raven said he saw the epic cycle as centered on Lady Glencora and himself identified with her. I would have thought it was Plantagenet who begins the film, inherits the money, is more active during the Phineas films, and outlives and shapes Lady Glen’s life. Plantagenet also embodies the idea of the gentleman Raven describes in his book of that title, someone marginalized, irrelevant to society since the 19th century (so basically from the time the ideal was conceived), a kind of tragic symbol of society’s hypocrisies.

Raven also meant us to laugh at both of them: we are not to identify with her views wholly any more than we are to empathize with Plantagenet’s. The corrupt Dolly Longestaffe’s description of the way the world works is after all accurate. The camera’s pictures of the protagonists and what they reveal of their inner life also escapes the writer’s and the directors’ and producer’s views too. Nonetheless, it’s revealing to see where Raven saw his allegiance. This suggest also why such sympathy for Silverbridge (Anthony Andrews) in the last episodes.

Raven’s Lady Glen is more infantilized than Trollope’s—who at least allows her acknowledgement of the bed scenes she is enduring at night as is Palliers and her sense of herself as a beast driven to someone to produce progeny). Raven does not see his women characters as the important actors in a social scene; they appear as powerlessly on the margins; their activity that counts is sexual and in private with men. He also does not allow the heroine sexual aggression, perhaps because if he had in a 1970s film adaptations she would be seen as evil. But she is the center we return to, and her statements capture the deepest questions of the part. Is not a honeymoon a time when two people are to come together? It’s not for politicking, or is it? What is a marriage about?

Barry Justice acts Burgo powerfully, effectively, he’s a man in love and yet utterly sybaritic, desperate for money anyhow and anyway (he has been given no means to earn a living, and no encouragement to do so); he has become utterly destructive, wild (as Lady Glen has the capacity to be). Lady Glen’s character is as yet capable of development (alas enforced moulding by her society through the agency of her husband). Burgo self-destructs while she is imprisoned. He looks his agon; her scenes evoke the question, why is she asked to live the way she does? Why cannot she have genuine companionship? The answer is a pessmistic and cynical view of how society works. Raven’s own.

After Lady Glen and Palliser have finished their sleigh ride, they arrive at a hotel in Basle and we are into Episode 7, “Switzerland.” This is the hotel Alice, Kate, Grey and John Vavasour, and then when Grey leaves, George are all staying at. (This is unlike Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? where just Alice, Kate, and George stay at the hotel at the opening of the book; in Trollope’s book only after Lady Glen and Palliser have faced her love for Burgo and he given up a potential office to take her to Europe,

do they meet with Alice by taking her with them and then only later encounter Grey—when Alice has had time to think about her hostile reaction to George and his demands and ways.) Raven’s Lady Glen is startled because her honeymoon is not to be a coming together in love of her and Palliser, but him meeting bankers. In off-hours he takes her to museums. She spontaneously rejoices when she comes across Alice.

Lady Glen (Susan Hampshire) first sees Alice (Caroline Mortimer)

The two women friends embrace.

Alice is her breathe of air. Raven’s Alice is also seeking to find what she wants out of life, to heal her wounds from George, understand Grey, and discover who she is what she wants from life on her own. It cannot be said she does this. Trollope’s Alice never does either—in Trollope’s book, it’s too hard for someone like Alice who has more complicated needs, deeper sensitivities and intelligence than Trollope’s Lady Glen.

Raven’s Burgo has pursued Lady Glen to this place as George Vavasour has pursued Alice. Burgo is sending Lady Glen letters, one of which tells her to meet him at a fencing school. She tears the letters, revealing that she in fact will not flee with him, but she does show up at the fencing school. This is fascinating in part because it anticipates precisely the use of sexual energy and metaphoric aggression found in the 1995 BBC Pride and Prejudice (where Colin Firth plays a fencing Darcy).

What happens over the course of this part (which Burgo cannot see and Lady Glen does not quite realize) isslowly she is edging towards a life at Matching, one as a political wife and hostess. She also in this film feels more comfort in Alice’s company than she can ever do in Burgo’s, partly because his ways give her no means to enter into companionship. In the novel there are suggestions with Burgo’s aunt, Lady Monk’s help, they could have gone to Italy together and lived in her money; that they could have enjoyed things like gambling together, found a gratifying if unrespectable and debauched way of life. At the close of this film (1:2), George has promised Burgo money and Burgo dreams of finding just the moment in time where he can tempt “his Glencora” to flee Palliser; Burgo’s mantra is how when he touched her she would (sexually) melt beneath his hand; when he gets that hand on her, she will be his “for good”—or so he dreams:

Burgo’s crazed desperate tragic face at part’s close

But we have just witnessed a second scene between Lady Glen and Palliser at Matching Priory where she has told him she must have companionship and what she feels is useful activity. He has not yet conceded the latter. In their first scene at Matching Priory together, he tells her the housekeeper will make arrangements for which of the guests sleeps where and also that she must consult him before inviting anyone as her invitation to the Duke is useless as the Duke goes to Cuomo in the autumn and never interacts with politicians at any rate. Here in this last of this part, he does concede her need for a friend. So he asks with an affectionate look on her face (he is learning to like her), Why does she not invite a friend, a woman her own age, Alice Vavasour and we have seen her response to this:

It is too late for Burgo.

I like Trollope’s Alice Vavasour myself. Trollope’s Alice is that rarity for me in Trollope—a heroine I can recognize aspects of my inner life in. Trollope’s Alice is austere, not grim (like Raven’s); I can also like Trollope’s John Grey who reads about the French revolutoin (and loves memoirs about it), and I am particularly fond of what Plantagenet develops into: he is in this part as yet very stiff and seems never to understand much about building private relationships with people he cares deeply for. We will see this in his encounters with his son Silverbridge (Anthony Andrews) in the final parts of the series.

In comparison to Volume 1, Part 1, Volume 1, Part 2 has many short scenes here as Raven seeks to fit in so much. He eliminates Trollope’s third comic story (about the Widow Greenow, partly I suspect because Raven does not consider materialism and philistinism a laughing matter).

As with my blog review of 1:2, I conclude with an outline of 1:2, and a few accompanying stills:

Episode 6: “The Wedding.” We see the coerced terrible moment, all pomp and misery; a juxtaposition of Burgo and George at the Club as at a death of a dream; Plantagenet and Lady Glen on the sleigh; and finally, Alice and her father, John, waiting for Kate and George to arrive to go to Switzerland.

Alice (Caroline Mortimer), Kate (Karin McCarthy) and George Vavasour (Gary Watson), the two girls going to Switzerland

Episode 7: “Switzerland.” On the terrace are Alice and her father and and Kate; then Alice and Grey. Lady Glen and Plantagenet arrive at the hotel, and we seed Lady Glen’s dismay at the plans Palliser has for the honeymoon (meeting bankers and going to museums, seeing the landscape); we see his strained cheerfulness and patience. George arrives, and Kate and George plot against Alice, and we find ourselves again on the terrace, with Alice and George over a telescope dreaming of adventure. Lady Glen gets letters from Burgo, tears them, spies Alice and the two groups meet and become one . Lady Glen proposes a trip to fencing school proposed; she hopes to send Palliser and John Vavasour off to museum, but (i a comically tragic scene), she discovers that the museum is closed and Palliser, ever gentle and accommodating, proposes to go with her to the fencing school.

Episode 8: “Fencing.” Burgo confronts Lady Glen as fencer, and there is a scene where she draws close to him which visually repeats the ring scene of her engagement to Palliser:

She is pulled away, rescued by Palliser.

Then we watch George and Alice on the terrace the night before leaving Switzerland. Kate has left them alone (she will pack). This is a powerfully romantic scene where George proposes intense excitement as a candidate Alice can back; reminds her of how he was like brandy (John Grey is a glass of milk), to which she says yes but the glass is poisoned by its vile contacts (and George’s attitudes):

They are fencing too.

Episode 9: “Glencora adjusts.” It opens with a comical yet nasty & sombre scene where the Countess of Midlothian (Fabia Drake) and Marchioness of Auld-Reekie (Sonia Dresdel) inform the Duke of Omnium (Roland Culver) that Burgo has been pursuing Lady Glen (he “sprang out like a demon king in the pantomime”) and they fear she will run off with him; the Duke shrugs it off, with the statement the lady must be taugh not to make her messes on the rug and provide an heir and spare first.

We then Lady Glen glimpsed imprisoned behind the Matching Priory barred windows; we have her scene with Plantagenet where it emerges she cannot easily take over making even the guest list as she doesn’t know enough, and her competition with the insinuating labor politician, Mr Bott. At Ely Grey asks Alice to name a date, pick material for their house furnishings; she begs for time and he says she’s ill. In the novel this illness may be interpreted as depression as well as sexual seduction; in the film Alice wants freedom to live in the town, be part of a campaign, is not sure she is in love with Grey enough to retire to the country (that’s in the novel too). In both novel and film Alice is seen as risking what’s worth while for something that would be ashes in her mouth, not useful to her (because she’s a woman).

Episode 10: “A New Candidate.” Now the politics of the film cycle begins to emerge powerfully. We first see George and Burgo at the club drinking, and this scene gives way to Barrington Erle and Dolly Longestaff discussing how acceptable Vavasour is (they will have to look into this). Then there is the election scene at the pub and back room between Grimes, Scruby and George. Back at Matching Priory Palliser disapproves of Lady Glen reading Balzac (and Mr Bott wins a round), but as he sees, she cannot find anything to do wth her life, and needs something real and meaningful, he encourages her to bring Alice out of real sympathy for her.

There is a growing affection for her.

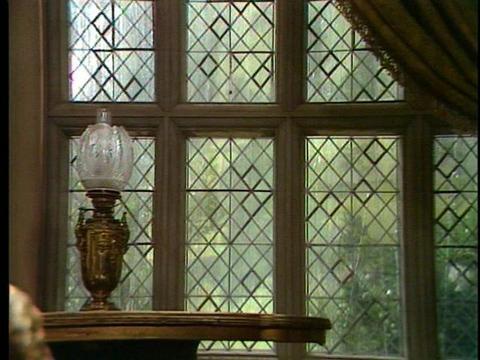

A repeated motif in the series or mise-en-scene is the Matching Priory windows in its front or drawing room (where many of the cycle’s important scenes will occur). These are seen from outside first and last (with Lady Glen when young imprisoned and Plantagenet when a widowed Duke looking out at her grave), and from within now and again. They symbolize the beautiful house given the young couple by the Duke of Omnium when they married. So they show us the the payment the couple had for giving themselves up to this society, its beauty of the old historically-rooted place itself, as well as the price (a kind of stasis when it comes to self-fulfillment):

This belongs to the fractured Arcadian outlook Inglis has identified as central to the 1970s film adaptation of high status novels on British TV.

I’ll write about Simon Raven’s Fielding Grey, Never Pay Late and The Idea of a Gentleman in the context of Michael Barber’s biography about Raven’s life & work another day.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Jennie on Trollope-l:

"HI Ellen and group,

This is my first post to the list, though I have really been enjoying lurking and reading the high level of discussion. High enough that I’ve been a little reluctant to wade in as an amateur! But having just finished “The Pallisers” this week after reading all of the novels themselves earlier this summer, this email caught my eye.

I was so impressed by the way that Raven dealt with the complexity of bringing all 6 novels and the world of Trollope into 26 episodes for a modern audience. I definitely enjoyed it more than “Jewel in the Crown”,and for exactly the reason I always enjoy Trollope. His loving characterization of the foibles in ALL of his characters and his confidence that he didn’t have to TELL us to like or admire certain of them, but rather leaving them to grow on us. I can’t say I was all that interested in “Lady Glen” in CYFH?, but by The Duke’s Children, well, I admit to some tears during the understated and lovely chapters on her death and the Duke’s

subsequent surprise at his loss.

Which brings me to something I was hoping other members of this list who have watched The Pallisers might comment on – Raven’s choice to set most of the action of DC before Glencora’s death. While it necessitated some finagling (like, why was Glencora not more involved in arranging things with the Duke before getting ill), I think it was a fine choice for this dramatization. Losing the fine Susan Hampshire with three episodes left to go would have let all the light and heat out of the series.

Thoughts? Thanks for letting me participate!

Jennie”

— Elinor Sep 2, 2:48pm # - Dear Jennie,

Welcome to Trollope-l. I’m delighted to hear you’ve recently read all the Palliser novels and have seen the films (or watched the DVD, if you prefer) recently enough that you can join in the discussion. I didn’t meant to say Scott or Taylor don’t have complex characters, and suggest that all novelists and film-makers too have to shape their characters to embody themes. The way a character is dramatized leads the reader to feel certain ways the novelist and film-maker wanted; these may be complex and multifold, but the meaning is there. Thus Trollope wants us finally to condemn George and also wants us to feel Lady Glen made the right decision even if she was deprived of independence and an ability to grow and change in ways consonant with her personality. Trollope values safety and chastity for women above all. Raven wants us to feel in the final episode of his film that Lady Glen always rightly regretted she had not been given the ability to choose, and the depth of the moving episodes in the last scenes between the Duke and his son and the Duke and his daughter comes from his finally acceding to give them true liberty, to trust them to become adults, or allow them to fulfill themselves. Silverbridge is a kind of surrogate for Lady Glen in Raven’s films.

I agree that the right decision was made to keep the Duchess alive until the last 40 minutes of the last episode. She is deeply involved in the political fall of Palliser, and the last episodes are about how the two of them cope with being out of office; the Duke has to cope with his not having been able to use power in the way he envisaged; she seems really simply to intensely regret losing it; she wanted to be on top to be on top. She also until the last episode is part of the development of the children and their characters. This is quite different from Trollope, but Trollope is interested in the relative failure of the Duke and Duchess’s marriage insofar as deeper happiness with one another as personalities is concerned. He wants to show us the Duke cannot let Lady Mary marry Frank because he is still unable to forget Burgo and accept Lady Glen’s attitude towards Burgo (a lingering regret). This is not what Raven shows us; Raven presents a couple who have become true companions even if emotionally and intellectually he cannot understand her, and she sweeps by his views as irrelevant (Raven thought the gentleman was irrelevant as he says in his book).

I did love the way she remained a haunting presence in the last 40 minutes of the last episode. Her picture is always seen in the room where the conflicts occurred. The Duke is last seen reading a book sitting in the window (the one I put up on our groupsite space and on my blog) and we see her portrait nearby. She was a partial loser, and life must go on, but her children will have more of experience life that they want than she did. Her deathbed scene and last words were important as well as the graveside scene and the Duke’s walk to the grave and walking in the Priory ruins with Mrs Finn (aka Madame Max).

I didn’t mean to say The Jewel in the Crown is not a fascinating well-done series. A criticism of the political perspective of a film is not a total condemnation of it; it’s an evaluation so we can see what we have before us. There is an important set of elements in The Jewel in the Crown that elevates it in some ways above’s Raven’s work.

Taylor’s depictions of women. He’s very sympathetic to all the women we see and women dominate the series. There are brilliant and touching performances by Peggy Ashcroft as Barbie, an aging companion of the rich lady, Mabel Layton, played wonderfully by Fabia Drake (making up for the caricature she had to do in the Pallisers of old woman as harridan-hag, corrupt, prurient and domineering); Judy Parfitt as the alcoholic middle-aged wife of a man imprisoned by war (she was Lady Catherine de Bourgh in the 1979 P&P, the best Lady Catherine I’ve ever seen), Geraldine James’s part is a gift (your traditional heroine) but not so Susan Woolridge as Daphne Manners. There are numbers of Indian woman actresses, and they are touching and subtle.

What strikes me is not only that he was the writer of the 1983 Mansfield Park a similarly subtle nuanced adaptation of Austen’s book which did justice to the women, but it’s typical for these 1970s productions to be more feminine. That’s the word for it. Love for Lydia (13 episodes for a book the length of Brideshead so like BV in its art) is another where a male book has been somewhat turned on its head to show the women’s point of view on subLawrentian outlooks (the book is by H. E. Bates).

Perhaps part of the backlash against feminism and by extension the depiction of women (turning them strongly into sexobjects of a different kind) produced the change one sees in the film adaptations of the 1990s where except for films like Emma Thompson’s S&S, Oedipal interpretations with a macho male in the center much more (partly due no doubt to Davies who writes so many of them, and for example, makes Lydgate central rather than Dorothea in the structure of his film).

It’s so hard to get these 1970s film adaptations too. When there’s a new version, the old one goes out of print. Perhaps we should rejoice no new version of the Pallisers has appeared, for Raven does not turn his women sheerly into secondary creatures—though he goes far in that direction.

I don’t remember the Raj quartet well enough and never read the fourth volume so I can’t say how closely or originally Taylor worked. I did like Staying On much better (as kind of coda to the roman fleuve, if that’s what it is) and it is about the sufferings and injustices of petty colonialists. I once planned to teach it and know it better, and can say the wife is central. Her death (suicide really) at the end destroys the man.

Let me thank you very much again for replying. I hope you become an active member of Trollope-l.

Ellen

— Elinor Sep 2, 3:07pm # - “Dear Dr Moody,

I just saw your blog on your work on the Palliser films. I’m finishing off my PhD chapter on Phineas Finn/Redux and would be interested to know what you make of the garotting of Kennedy in Finn and the presentation of Finn’s ‘life preserver’ in Redux so do keep me informed of your progress!

Emelyne Godfrey

Birkbeck College” She also wrote on Victoria: "Dear listservers, I am finishing off a redraft of my theory section of my PhD (soon to hand the thesis in!) and just was wondering if anyone knows of any key sources which look at male physical vulnerability eg. threats of violence from other men. I have looked alot at eg the Sherlock Holmes canon and other phenomena like the garotting panics but perhaps I may have missed a few sources to mention? Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes on male rape fears in the works of Dickens but I am interested to know if there are any other sources on that I should be aware of? Any suggestions are most welcome! Emy."

— Elinor Sep 2, 4:20pm # - “Dear Ellen,

I read on your blog that you “copied down every word of the screenplay” of the BBC The Pallisers. I have the DVD’s but unfortunatley there are no subtitles and for me (I am Italian, but I am fond of 19th century English Literature) it is often difficult to understand the dialogues in all parts: it would be very helpful if you could send me your transcriptions.

Best regards,

Alessandra La Spina”

— Elinor Sep 3, 7:52am # - Dear Alessandra,

Well I’m not there yet in this sense: I am a Pittman stenographer and I am copying down every word in sten. I do write some out in English in pencil, but mostly I sit there taking it down in stenography.

I eventually (not this year though) may type up my notes. Then I’ll announce it on the blog and if you keep up with the blogs just on the _Pallisers_, you’ll hear when I’m finished and if and when I’m typing up my notes.

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 3, 7:54am # - If what is wanted is male threats to other men, there’s an enormous amount of it in Trollope: many of the novels have one man threatening another (e.g., George Vavasour threatens John Grey in CYFH?, Tom Tringle, Jonathan Stubbs in Ayala’s Angel), demanding the other fight a duel (Lord Chiltern requires Phineas Finn to fight a duel with him, Tom Tringle again bothering Jonathan Stubbs); there are spontaneous fights which end in death (often over sexual outrage, as when brothers kill the sisters’ seducer in The Macdermots of Ballycloran and at the opening of Dr Thorne). But male fear of another and a sense of vulnerability is harder. Yes Phineas Finn walk about with a small club (“lifesaver” gives the paranoia away), but as in most of the cases of men in Trollope, Trollope does not show them as fearful of other men. This is part of the masculinity code of the admirable man. The man who fears duelling or other men would be seen as a coward. I believe John Grey prepares for George Vavasour, but does not fear him. One man who is fearful is cousin Henry (of the novel of this name) and everyone in the book despises him; further because he’s afraid they go after him all the more. This latter seems to be the rationale for Trollope’s advising (if it’s advice as novel writing) men not to be afraid. Trollope seems to think the stiff-upper lip and pretense of non-fear and non-perturbation important in life: a female, Mary, Lady Mason, is able to persuade the community she didn’t do a forgery only when she can pretend to stand before them all in a court looking fearless; the minute she becomes shattered or nervous, the community is presented as suspecting her guilty (her so-called friends too).

It’s interesting to me that most instances of threats, challenges, beating one another up (as in Dr Thorne Frank beats up a man who jilts his sister) have to do with sexual jealousy or a male’s idea his pride or “honor” has been besmirched because another male seduced his sister or is after “his” target (woman he loves). Yet the male who walks away if fearless (not nervous about the situation) is deemed noble, say Plantagenet Palliser in Can You Forgive Her? over Lady Glencora’s love for Burgo Fitzgerald. Again when the male shows sexual anxiety and insecurity, he is presented as weak, even despicable and in Trollope such males can go mad (Louis Trevelyan in HKHWR and Robert Kennedy in the Phineas books). So Eve Sedgwick Kosovsky (spelling?)’s book is central here. They seem not to beat one another up about money; only poor people in the street set upon one another over money, “low” types (say the street park people who attack Emily Wharton’s brother in Prime Minister), or (anti-semitism here) when Emilius seeks out and kills Bonteen with a small club because Bonteen is trying to protect Emilius’s wife’s money from Emilius. This seems to me unrealistic as fights over money were surely then as common as today; other kinds kinds of spontaneous violence in family—there Trollope does occasionally show men beating up their wives or daughters (Melmotte, Mr Hurtle in TWWN) but he seems to disapprove of the woman who fights back or leaves the husband and he shows no other kinds of familial violence, fear and threats (say over money directly; they grow angry but they don’t attempt to beat or kill one another, only the very lowest type knaves-desperate men dream of it).

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 3, 8:38am # - From Patrick Leary:

“Although its main thesis concerns violence against women, Martin Wierner's Men of Blood: Violence, Manliness and Criminal Justice in Victorian Englan (2004) is nevertheless a key text to consult for anyone wanting to explore the social and judicial contexts of male violence in the 19th century. The second chapter is devoted to male-on-male homicide.

—Patrick”

— Elinor Sep 6, 9:47pm #

commenting closed for this article