Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_Pallisers_ 2:4: The Crisis and a Choice Made · 25 October 07

Dear Marianne,

I carry on with my summary and analysis of each part and, within these, distinct remarkable scenes from the 1974 26 part BBC Palliser film series.

Volume 2, Part 4 is shaped more tautly than the previous three parts. Its narrative drive brings us to the dark festival climax in Lady Monk’s (Helen Christie) ballroom where on the terrace Lady Glencora Palliser (played by Susan Hampshire) says no to Burgo Fitzgerald’s (Barry Justice) scheme for them to elope and flee to Europe together. He proposes they live as man and wife despite her marriage to Plantagenet Palliser (Philip Latham) on the grounds they still love one another deeply, are man and wife with their hearts and could be with their bodies, and the marriage was coerced, a profound violation and betrayal. Her response is it’s late; there’s no going back. They cannot now marry with respectability and money. What would have possibly been beautiful (though perhaps not too) will now only end in ruin and loss for her as the loss of her (and her fortune) has been for Burgo. She has also begun to understand what a good man Plantagenet Palliser is, and that together they can make a life in which he will flourish by gaining power to do the good he intends, and she by having a position others will respect and admire. How she will use this she cannot yet see, but instinctively she anticipates it in the climactic scenes with Palliser where she takes on a hollow posturing.

I want to make note of something important in this part. In Raven’s script and this film Lady Glencora makes the decision not to flee with Burgo. In Trollope’s novel the character Lady Glencora does not herself make a decisive break from Burgo; the feeling of Trollope’s text is she is prevented from going and pressured into rejecting Burgo by those around her; that she remains wavering may be seen by further scenes in Can You Forgive Her? where she can barely stop herself from taking his offer (Alice’s presence prevents this). Trollope’s presentation make more sense of the character Palliser’s own decision to abandon his pursuit of place (the Chancellor of the Exchequer) and take Lady Glen on a European tour. In both Trollope and the film Palliser no longer insists on the idea that his wife’s previous or continuing love for Burgo “does not signify.”

This decision is more important for the Palliser films than Trollope’s books as a cycle since the BBC films’ stories are rearranged to make the story of Lady Glen and Plantagenet Palliser the central core of the series. In Trollope’s Palliser or Parliamentary novels the stories of the lives of Lady Glen and Palliser only partly dominate the first book (CYFH?) and the last two (Prime Minister and Duke’s Children): they are not the main story in CYFH? (that’s Alice’s) and compete with the story of Edith Wharon and Ferdinand Lopez in Prime Minister. The Palliser story is marginalized into a corner of the others which in Trollope are given over to Phineas Finn and Lizzie (one does not give her the dignity of her full name), Lady Eustace.

In the films only the very poor two parts which allow the matter of Eustace Diamonds much changed and debased, misogynistic and anti-gay (or aligning itself with the deformations of masculine norms known as macho), the matter, I say, of Lizzie Eustace (Sarah Badel) and (in the film version) Lord Fawn (Derek Jacobi) to dominate the films do we lost sight of the Pallisers. The Phineas (Donal McCann) material does dominate over the plot-design of the filmic story, but his story is interwoven with many scenes and events of Palliser as a politician and the men’s friendship (Palliser and Phineas) traced while Lady Glen’s friendship with Madame Max Goesler (Barbara Murray) is developed. So Lady Glencora and Plantagenet remain figures in hinge-point or crucial scenes.

Raven retitled or gave a definite title to all of Trollope’s books because he resaw them and placed at the center the story of Lady Glen and Plantagenet. In the novels this story functions more in the manner of Balzac (who at a dinner Trollope said was his predecessor in a certain way of writing—meaning romans fleuves), recurring continuing presences which unite the fictions but do not dominate them.

By giving Lady Glencora the dignity of a decided no, Raven does restore to her some measure of dignity and autonomy. It is true that in the final scenes of the this episode we see Lady Glen in a child-like white nightgown nursing a baby doll.

In this scene the first (and thus very exciting) voice over of the film is used. We hear Burgo’s voice saying to her this is their last chance for any happiness; she is his wife or will be of his heart, body and if he can in law. Over and over she is listening to this in her mind. On her face is this twisted ravaging. Meanwhile (and the feel is she senses this) below her window, there is Burgo looking, waiting, hoping for her to take their “last chance”:

It seems to me (as it does to other people who study and write about film, and certainly the film-makers themselves—like Truffaut and Lean and others who have written about their films—also TV film-makers) that the real meaning and depth of films is in the pictures, the stills, the close-ups, the mise-en-scene all that is not verbal, and these project a woman intensely violated and perversely turned back to a child.

The effect of her decision does remain ambiguous. The film’s visual clues do present her as robbed of all autonomy, turned into a child, a version of the doll she nurses. We see her earlier with it in this episode, sewing its hair while her husband is out in Parliament delivering an effective speech in debate with the Chancellor of the Exchequer):

She will have no effective agency with Palliser; she will be his baby-machine. She has no connection with the outside world but through him. She does show she will buck him when she and he are going downstairs and she insists he dismiss Mr Bott for good; Hampshire’s performance seems to me to insinuate a self-satisfied complacency after the crisis is over; her life will now be one of performance in public and admiration as a society hostess eventually. Need I say this too is not Trollope’s angle on her? Trollope does not see success and social life from the same utterly disillusioned and cynical angle Simon Raven does.

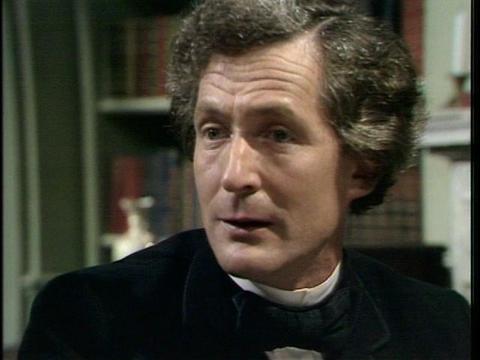

Raven does just to Trollope’s angle: safety lies with Plantagenet Palliser. We see his finer nature come out in a scene where after Lady Glen has treated a speech he triumphed in at the house (told by Mr Bott, John Stratton) with some tart mockery (insisting on the baser motives and behaviors that surround him), and Alice defends her uncomfortable reaction to him, he tells Alice he wishes he had such a friend as she means to be to Lady, and that he has been angry and unreasonable. The stills convey his ability to humble himself:

And Lady Glen’s spontaneous admiration for him and reactive trust and generosity herself:

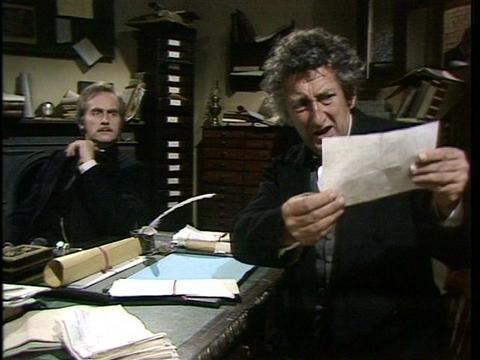

The parallel plot-design has George (Gary Watson) and Alice Vavasour (Caroline Mortimer) moving towards but not yet reaching the climax of their engagement. There is an important change in point of view from Trollope’s books here too. As told by Raven, George’s story is of a man who was not born to wealth, power and prominence, but tried to get there and couldn’t because he hadn’t the wherewithal and will be gouged, like a tissue the clever operators someone blows their nose in him. Mr Scruby is brilliantly acted by Gordon Gostelow in scenes where he astutely never mets George’s eyes but when he must. Here he is counting the note signed by Alice (“a lady’s name makes him nervous), which George has given him:

We once again glimpse the bully Mr Grimes (James Berwick), but only in the rough election scene where George is chaired and throws him away, the supine self-interested non-thinkers Barrington Erle (Moray Watson) and Dolly Longestaffe (Donald Pickering) will exclude him.

George does have genuine ideals of a sort: in this episode he gives an eloquent (according to Palliser who is listening) maiden speech against the ballot. Importantly too, Alice does not turn from him in deep sexual revulsion, but is deeply attracted to him and he offers her sincere affection and seems genuinely to yearn to make her his companion. Their scenes are of two people growing closer together, until he makes the mistake of seeming to want to move into sexual interaction so strong that she draws away in fear and trembling:

When she rejects him, he has the earnest hurt of sincere man:

In this scene (as with Trollope’s Alice), Alice says it is too soon after she has broken with Mr Grey (Bernard Brown), but when she defends George against the charge he is there to take her money, may have a venereal disease, is sexually promiscuous, unlike Trollope we are given no hint of evidence that these charges are accurate (at least as yet).

Raven criss-crosses parallels and contrasts between the central pairs (Lady Glen between Plantagenet Palliser and Burgo Fitzgerald; Alice between George Vavasour and John Grey). George’s struggle to establish himself parallels Burgo’s struggle to get Lady Glen and use her and her money to establish them as an independent couple (if he can control his drinking—and we are not sure he has the strength of character to do this, but that he wants to is clear). Alice seen as a much stronger woman than Lady Glen (not cold as in Trollope). Here she is holding her own against her father’s (John Glyn Jones as John Vavasour) accusation George is syphilitic and wants her for her money and her grandfather’s (Donald Eccles as the aged squire) comment she changes her mind a lot (John Glyn Jones)

Similarly the way John Grey is acted, he is not an apparently serene unflappable man, but he shows his vulnerability and need of Alice, telling his prospective father-in-law, John Vavasour (John Glyn Jones) that he is glad to spend his fortune and only wants her back and on any terms she pleases. He will take her with nothing—as Burgo is prepared to take Lady Glen:

The conversations between George and Alice are presented so he pressures her to be his wife first and really cares, and thus parallel with Burgo and Lady Glen whom Burgo pressures to go away with him and be the wife of his heart and his. Meanwhile George is gradually separating himself from Burgo since Burgo has no serious occupation in life; in one scene where Burgo is pressured by Lady Monk they kiss on the lips and it seems may have become lovers. So Lady Monk (a corrupt woman) becomes Burgo’s confidant, a definite down-turn in Burgo’s status.

The effect of all is quite different from Trollope’s books. I suggest that the term “semi-original” (which I’ve come across in early studies of BBC mini-series and single episode plays) is the most appropriate for the Palliser films. In this part Raven will take lines from several different scenes in CYFH? and utterly rearrange them; proportionarlly he has many more scenes of money exchange between Mr Scruby and George than Trollope—money glitters out at us in the women’s jewels, garments, and the luxurious rooms and houses as a kind of sinister substance driving the action whatever the motives the characters profess.

When Trollope’s Alice goes to Westmoreland to help Kate care for their grandfather as he begins to die, Can You Forgive Her? turns sublime at moments, picturesque at others (in the descriptions and original illustrations); by contrast, Hugh David and his team give us gothic scenes of sombre darkness with the aging Squire (played magnificently by Donald Eccles) as a savage domineering old man who has no understanding for his grandson’s career ambitions.

The aging patriarch’s words echo those of the Duke of Omnium (Ronald Culver) when (in Part One), the squire agrees to countenance the marriage of Alice and George as one which will “do very well for the property” and bring together “blood” lines. He differs from the Duke in not having his urbane appreciation of the need a man might have for big money now and so puts a wrench in George’s relationship with Alice (unlike Trollope’s George, Raven’s really does not want to take her money before she marries him).

************

I again provide a brief resume of the episodes in the Part and a few more significant stills. It is hard to chose from among these as so many are charged with meaning.

Episode 16. “The Return to London.” Here we see Alice’s strong nature come out as she copes with her father’s adament condemnation of George and her grandfather’s needling words. Burgo and George are pictured together briefly: George tells Burgo there will be a bye-election and now he must have more money; he voices hesitation in taking Alice’s money which he sorely needs, and Burgo is the cynic: “Scruples, old fellow?”

The title of the episode, The Return to London” highlights the scene of Lady Glen and Plantagenet coming back to their house.

The establishment shot shows us a gorgeous room, much gold. Lady Glen is so relieved to be back, but Plantagenet utters a line from Wordsworth when he sees the letters on a table: “The world is too much with us.” He does not know the letter is actually from Burgo to Lady, and that she lies about it to him, all the while it prompts an intense yearning in her eyes and posture:

She has felt the most real connection and emotion in weeks upon reading this man’s few words.

I like how Plantagenet persists in trying to teach Cora (he is now calling her Cora, a sign of intimacy) not to compare people to animals. She has said he has no more vanity than a lobster, a way of ridiculing something fine in him.

The episode includes the first of the two brilliant scenes of Scruby and George, much of which is original invention on the part of Raven. Mr Scruby (Gostelow) just about never makes eye-contact with George (Watson): this is skilful ruthless bullying. You see it’s not Scruby’s fault this money is necessary.

Episode 17. “Alice’s Money.” The scene is Alice’s drawing room in London, the players George and Alice. Raven has transformed Trollope’s Chapter 35 (“Passion versus Prudence,” in the 1974 Penguin edition by Stephen Wall, pp. 375-80). Trollope’s Alice is appalled that George comes to her; Raven’s Alice is eagerly running to him at his steps. In Raven’s scene, Alice must tell George, Squire Vavasour will give no money to George, but settle the estate on her when they marry; she offers him money but puts off marriage and he is shamed and reluctant but gives in. (Trollope’s George feels no shame in these ways and is only reluctant because his sense of himself as a macho male is wounded). In Raven’s scene, we are made to feel sympathy for George after the scene with Scruby, and this scene is juxtaposed by another scene with Scruby where we see George fleeced.

This is followed by a scene between John Grey and Alice’s father, John Vavasour where Grey offers to put his money in place of Alice.

Again Raven has taken material from Trollope’s scenes but rearranged it; this time the emphasis is on Grey’s tenderness. Mise-en-scene notes are important in the series: as Grey speaks we see behind him a delicate vase (=Alice in his mind). Throughout this Part the stills show the importance of documents in the characters’ lives.

The scene is then reinforced by another in Alice’s drawing room: a letter from Lady Glencora Palliser arrives in which Lady Glen has asked Alice to come to her, but her impulse to go to Lady Glen is forestalled when John Grey enters, she turns in a gesture of intense emotional distress before he comes in, but Grey is non-threatening, and their talk is genial, one of dear friends; the importance of his trust in her and respect for her, and his non-agressive sexually is shown in her face and gestures. Behind them we see two lovely vases in a window, ever so comfortable. In the next scene we have Lady Glen playing solitaire and given comfort by Alice’s arrival. The still here imitates idyllic illustrations of the 1860s such as we find in Trollope’s novels.

Lady Glen confides that Burgo has written her and Alice says she must put it from her.

Episode 18. “Defending Glencora.” The one defending Glencora is not Plantagenet but Alice. The point of this episode or shaping idea is to contrast how Plantagenet has serious state business and Lady Glen none; Lady Glen has no sympathy or understanding of his aspirations. In the first scene we see Palliser triumph in speaking in Parliament against the Chancellor of the Exchequer and how he gains admiration and respect. He comes back to find her sewing the hair on a doll. She is infantilized, and they clash as he wants to invite Mr Bott for dinner but is still trying to control her by keeping Alice from her:

The pre-dinner scene is important. Much strain and tension going on but finally put to rest by Plantagenet who concedes he has been at fault in blaming Alice. This is the scene where Plantagenet’s finer nature comes out (which I described above) and he owns himself to have been in the wrong.

The parallel here of an idealizing lesson typical of conventional literature for a long time: good men are patient, kind and tender. They do not dominate the women they want through physical brutality; they are moral, ethical. This is the essential parallel of Grey and Plantagenet, and Raven (who sympathizes with George) makes his George partake of these qualities.

These may be qualities women viewers ideally dream of. Mr Knightley, Mr Darcy, Ashley Wilkes. To me this is more than understandable. It’s a prime motivation in the presentation of male types in post-feminist books & films like The Jane Austen Book Club

Meanwhile George is elected and we see him in a scene of uproaring nonsense and noise at the pub, sandwiched between Mr Grimes and Mr Scruby who are prepared to fleece him again for the next one. Then a powerful scene with Alice where she at first succumbs to an intense sexual attaction to him. It’s important to remember that Trollope’s Alice is not attracted to George; Raven’s is and is contradictory in her impulses: she pushes him away out of a motive for safety (he must not take sexual advantage of her) which parallels Lady Glen’s pushing Burgo away at the moment of crisis.

Mr Vavasour comes in and tells of the grandfather’s illness; Alice must go to Vavasour Hall and thus will not be there in London for Glencora at the ball. Lady Glencora enters and is frightened to realize she will have to cope alone, decide alone.

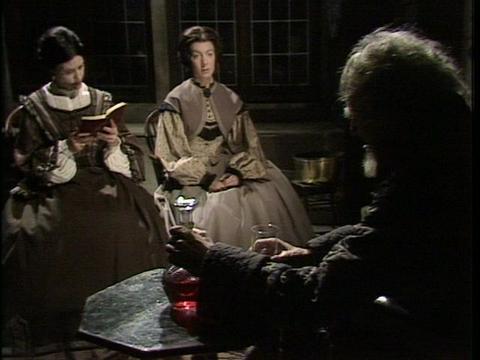

Episode 19: “The Ball.” This is the height or climax of this episode and may be regarded as containing one of the pivotal climaxes of the whole series. Very effectively it opens on a gothic scene of Alice and Kate (Karin MacCarthy) at Vavasour Hall with Squire Vavasour.

About these powerful scenes and the mise-en-scene of sombre blacks and browns, on Trollope-l Nick Hay commented:

“Grandfather Vavasour’s home in Cumberland is portrayed as wrapped in everlasting stone, a sort of ultimate Cold Comfort Farm in which the miserable old miser keeps everyone else miserable, rather like Lord Stapledean in Trollope’s The Bertrams.”

I replied: There is a studied effect made by the landscapes, houses, and costumes meant to project a vision somewhere between Trollope’s and Raven’s—only Trollope found walking in the northern moors exhilarating. He loved it, and he makes George vividly alive as he marches through. Earlier in the novel Trollope wanted Phiz to make an adequate picture of Alice and Kate reading a letter while they walk in the downs. And Lady Glen is electrified by her time in the gothic Matching Priory. The palette of this episode has sombre colors: there is little spring-like or gay until the ball: lovely ivory colors at best with brown dominating.

We do see the vulnerable woman giving in: the single and poor Kate Vavasour. Squire Vavasour is grateful. (In Trollope’s novel the old squire leaves Kateand in Trollope’s novel cause George to regard Kate as his greatest enemy and physically injure her):

And so by contrast and suggestive ironic parallels we reach Lady Monk’s ball. This is an electrifying series of vignettes arranged around the central ballroom; an externalized kind of voice-over is used as while we watch Burgo and lady Glencora dance we hear the voices of others discuss them as the changing shots move swiftly back and forth, close-ups and sudden swerves away: the central event will be Lady Glen and Burgo’s getting together to dance as we saw them do in Pallisers 1:1. We in effect return to 1:1, only what was hope is now frenetic tension. It is too late. In Victorian terms, Lady Glen has lost her virginity to her husband and so cannot go to another man. The music again plays on throughout the episode.

As the sequence of scenes opens, we are terrace and watching Burgo and Lady Monk: it’s hinted they may be lovers; he has the money from Lady Monk, and is ready to remove Lady Glen if she will go off with him.

We then get a brief scene of Lady Auld-Reekie and Midlothian on the way to the ball: they are two spiteful hags in green. They have ruined Lady Glen’s chances for deep happiness and are going to the ball to make sure their tyranny sticks.

Then we see Lady Glen, Palliser and Mr Bott mount the stairs and be pulled in by Lady Monk:

Lady Monk is the great spider lady and when she appears whatever she approves of feels sinister and certainly something Lady Glen should avoid to keep her peace and sanity, let alone solvency.

There is a certain quiet but improbable comedy in the first phase of the ball as we are asked to believe that Palliser has no conception that Lady Glen is eager to dance and himself carries on a conversation with Mr Bott about politics, and oblivious to all around him.

He leaves early, telling her only not to overheat herself. She is now all alone:

Note how Lady Monk is photographed above her so as to hit a sinister note: what awaits her if she runs off with Burgo is shame

and living with cruel people.

Burgo seizes his chance; Lady Glen sees him across the floor, and is partly driven out of resentment to accept his offer of a dance when her aunts come over and like dragon-ladies attempt to control her. Now the camera catches them dancing as other pairs look on and comment (as in Pallisers 1:1). The music is very Strauss-like and begins to play and continues to do so on and off for the rest of this episode. It’s a dance of life and despair: life for Burgo if he can capture Lady Glen (dressed in blue like a Cinderella princess), and in term of risk and probabilities an offer Lady Glen must refuse even in despair. We are not allowed to forget the George-Alice story as among the pairs are Barrington Erle and Dolly Longstaffe who talk of how George is going to make his maiden speech, and express an unexamined prejudice against a man who speaks too quickly.

Episode 20: “Burgo’s Plan.” The first scene is in Parliament and George is making a speech on behalf of the secret ballot and we can see Palliser approves of it and the house seems to cheer George’s candour and desire to free the process of bullies and corruption. But Palliser is interrupted by the well-meaning Mr Bott. We are to understand in the film that Mr Bott really means well, even if (as Bungay suggests) the implication about Lady Glen is ruinous to her, not clearly just and won’t be appreciated as making mischief. Mr Bott who whispers in his ear he must not stay to hear George’s all.

The camera brings us back to the ballroom and we catch Lady Glen and Burgo dancing and it is now that he reveals his plan.

Some of the words are from Trollope, but most are not (Ch 50, Penguin p. 537) It begins with a kiss on the terrace:

Then Burgo speaks:

Burgo: “Everything is arranged, Cora, we can be gone this very night.”

Cora (breathless): “I … no …” [camera switches to others watching them] “Oh, Mr Fitzgerald, take me from the floor and leave me and do not return.”

Burgo: “Cora, you cannot mean that.”

Cora: “Please, Burgo, do as I ask, for the sake of the old days, of which you spoke .. they can never come again.

Burgo: “They can. They shall.”

Cora: “I tell you, Burgo, we are noticed.”

Burgo: “Cora, come … [They flee to a terrace.] Nothing else matters so long as you are minded to do what I ask.”

Cora: “But I am not minded and you insult me by proposing it.”

Burgo: “If you want to be my wife it is no insult.”

Cora: [whispers] “How can I be that?”

Burgo: “Come with me abroad Cora. You may yet be my wife.”

Cora: “If that could be.”

Burgo: “My true wife, the wife of my heart and of my body.”

Cora: “Oh, Burgo.”

Burgo: “Come with me, Cora. Come with me tonight.”

Cora: “No … no.”

Burgo: “Cora there’s a carriage waiting 100 yards from this room. I’ve money, I’ve tickets to France, I’ve planned everything.”

Cora: “No, no, no. This is madness even if I wished to come. I’m surrounded, Mr Bott …”

Burgo: “He’s no longer here.”

Cora: “My aunts.” [They come into view.] There they are. [They are at the door and walk onto the terrace.]

Cora and Burgo flee back to the dance floor and the moment is over. He keeps at her, telling her she can retire and go down the stairs, but she has in effect rejected Burgo on her own before her husband returns. Her relatives do not give her credit for this; only Bungay trusts her: ah, now I see the purpose of that pun, a gay man in disguise, perhaps surrogate for Raven himself as he was for Trollope in the novels. Only Bungay would say he sees only a very pretty lady enjoying herself immensely dancing with a gentleman. He looks far gloomier and clearly wished she had been able to get Plantagenet to dance with her (which he encouraged her to do in a vignette, but Palliser shook her off lightly and with little trouble—revealingly about her character), but he trusts her to decide. This would seem to validate her decision as one of autonomy, the grown up adult who sees that Burgo means misery in the end for her, poverty and desperation as the intense love dies.

The decision is also presented historically: we are to read the films as Victorian stories (the sets and costumes shout this) and so the woman who is no longer a virgin (gasp!) cannot flee the man who took her virginity (certainly never) and remain respectable in any one’s eyes; she has no property, as this is now her husband’s, and the time is passed. She regrets this but prudence keeps her in her prison.

To my mind, her conduct for the rest of the ball shows her to have less depth of feeling than Burgo. She spies Plantagenet on the stairs, and suddenly gains animation and confidence, and giggles (!); she plays the gay lady in a performative speech to Burgo as Palliser comes over. I can see why Susan Hampshire was perfect for the part: as she and Palliser come down the stairs, she turns and demands he never allow Mr Bott in the house again (some irony here as it was he who sent Palliser and he is himself a powerless man). She acts all the grand dame: her happiness will now be in playing the games Lady Monk plays: gaining the superficial admiration of others; Hampshire does pettishness, petty gestures (at Pallisers) and posturing very well. As she goes down stairs with Palliser she has indeed made her choice; she looks proud. He points with his hand to where they must walk, but she has chosen to walk with him.

She has chosen what the aunts wanted her to chose and as we see them go off the camera switches to the aunts in triumph. We see Burgo left standing there, with a look of sheer pure pain on his face, total desperation but an adult, someone free who would have acted had she had the courage to do with with him.

The concluding alternating scenes insist Lady Glen’s has been a limited sad choice; it insists on the grief and the loss. The camera first catches Burgo’s feet walking on the cobblestones, and we hear the beat.

Then we see his face. He crosses the square and we glimpse a woman overdressed who is a streetwalker. The camera then switches to Lady Glen in her bedroom, a ravaged child who clutches a doll. As the camera moves back and forth between Burgo looking up, and Lady Glen preparing for her bed, we realize he has walked to her window and is waiting outside. She cannot know he is there, but he is in her mind and heart. We now get the second but first full use of voice-over of the series: the inward words a character is hearing in his or her brain. We hear Burgo’s eloquent plea (“you will be the wife of my heart”) as we watch Lady Glencora’s face; she is hearing it in her mind’s brain. As it’s the first of the series like the kiss between George and Alice in the previous Part, this has power. She turns out the light and goes to her bed.

We watch her lie there and then watch him hunch over and walk away. The series music is heard faintly and then resumes in full force.

I feel today film-makers would not be able to get away with presenting Lady Glen in a virginal gown going to bed. They would have to show Palliser demanding his sexual “rights” and this imposition would turn a scene of grief and loss into one of violation no matter how gentlemanly (awkwardly) Palliser was as he went about it. This would be out of kilter with both Raven and Trollope’s Palliser.

To expatiate through the parallel: Alice and George’s story is by no means resolved. She has yet to make her choice between George and Grey permanent. He has gotten into Parliament, but his means are staying there are tenuous, and while he is not presented as the violent, venal, and unprincipled man he quickly that under pressure he quickly becomes in Trollope, he has as yet shown no definite strength of character in the loving way Raven and Trollope’s John Grey has. Plantagenet will enact a parallel to John Grey in the next episode. It’s revealing that in his moment of crisis the film-makers will also resort to voice-over (in his case Lady Glen’s words that she does not love him, and does love Burgo Fitzgerald revolve in his mind).

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article