Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Pallisers 6:12: Compromise and Resignation (3) · 13 June 08

Dear Friends,

And now my third blog on this second transitional part (the first transitional part was 3:6) of the Palliser series. We’ve had transcripts of scenes (“Discords”), a thematic summary (“Isolated People Herding Together; Lonely Friends”); now I offer a concise summary of its episodes.

As with the earlier transitional part, a horizon is reconfigured using soap opera aesthetics, but the result is not a new stable mood for a single overarching story, perhaps because Raven could not in the 1970s see his way into presenting Trollope’s story with the kind of cynical frankness that could really provide an indictment of society analogous to the one found in Trollpoe’s Eustace Diamonds.

He had first of all unlikable and unsympathetic characters at the center (see “The Introduction of Lord Fawn”. One solution for the lack of appeal of such heroes and heroines, is to present them satirically. While the first three scenes including Fawn (Derek Jacobi) and Lizzie Eustace (Sarah Badel) are parodic, burlesque the characters and present them from an unsympathetic ironic distance, Raven doesn’t keep this up.

As I wrote yesterday, what Raven does is substitute elaborate at greater length and invent scenes for his likable hero. For a third time we have the scene from Phineas Finn (Ch 72, “Madame Max’s Generosity”) where Madame Max or Marie (Barbara Murray) offers herself up to Phineas (Donal McCann), hand and body and money, and now he is so clearly desirous of her, her mate, and sorely tempted and he tells her he can’t and he can’t tell her why.

An important change is made in the story of Phineas’s marriage to Mary (Maire Ni Ghrainne). Trollope’s Mary does understand and support Phineas’s decision to vote for Irish Tenant Right, and he willingly engages himself to her, and persuades himself he does love her; Raven’s Phineas is (it seems to me) to be understood as deliberately trapped by Mary (she teases him and allows him to have sex with her because this is the way she thinks to hold him to her), she demands an an engagement and promise of marriage, and then when she discovers she is pregnant sends him nagging (yes) letters requiring him to return to Ireland and marry her. We see him walking in the park after he has refused Madame Max looking weary and unhappy.

Phineas (Donal McCann) harassed, depressed walks alone in the park

In the scenes of Phineas and Mary’s marriage, we see he is out of his element, not using his talents, is constricted, restless. In the scenes of their early marriage, we see he loves her, but they do not share the same interests or knowledge (which she voices awareness of) and how long his resignation or compromise would have lasted we cannot say (the reader of Trollope knows Mary will die in childbirth, and so all the talk about her plans over what to do when “her time” comes have dramatic irony).

The parallel (whether intended or not) is with Frank Greystock (Martin Jarvis) and Lizzie Eustace: Lizzie clings to Frank, and she is the wrong partner for him. Unkind as this feels, Phineas’s true partner is Marie Goesler and he is kept from her, as Frank’s true partner (never seen) is Lucy Morris, and he is kept from her—though for different reasons, for Phineas out of love and decency, for Frank for sex and out of delusions about himself as a man.

Lizzie (Sarah Badel) aggressively offering herself to Frank Greystock (Martin Jarvis); she is surrounding him, entrapping him with her hands

The Phineas/Marie/Mary material is powerful, full of ambiguity, and probably relevant to viewers as much today as it would have been for Trollope’s contemporary audience. As Nick Hay wrote on Trollope-l, near the center of Eustace Diamonds, out of Trollope’s Lucinda Roanoke and Lucy Morris stories

“two and a half really bitter and painful chapters centres on Lucinda, then two and a half chapters of narrative events – the events at the heart of the novel’s plot, the theft of Lizzie’s safe; then an even more bitter and painful chapter about Lucy, then a final coda chapter which is distanced, playful, ironic. In fact the events at Carlisle become utterly squeezed out because they are surrounded by matter of much greater emotional, and indeed intellectual, impact. There is movement from the internal to the external – and the world (Matching Priory) of course judges the external (as we see in Chapter 47).”

So the continuous grave drama and serious upright stance of the whole of the Phineas matter (which includes the Kennedy story) is the substitute for the lost proto-feminist matter of Trollope’s book.

The theme which unites the different threads beyond isolation and loneliness is compromise. The serious characters compromise, and that Lizzie won’t is her undoing. We have compromise partners throughout: the Duke and Madame Max do not when Lady Glen leaves the room go on with more titillation about Lizzie, diamonds and nurses, but rather she tells him of Vienna; there’s Lizzie and Frank, having some form of illicit sex (while just like Fawn he doesn’t get too involved), and Mary and Phineas, staid married couple, versions of Us, Everyman and Women, counterparts to Plantagenet Palliser who is now the husband home on weekends to see the little wife taking care of the old men and their children (children nowhere in sight though). Lord George de Bruce Caruthers (Terence Alexander) and Mrs Carbuncle (Helen Lindsay) are an ultimate in compromise: resigned to one another, helping to sell one another.

The summary:

Episode 16, “Recovering”: Scene 1) Matching Priory, Duke’s bedroom. Lady Glen and Duke playing backgammon together. A little allegory of Lady Glen’s character is suggested by her justification of her careless playing; thematically it links to Lizzie Eustace who doesn’t begin to guard her vulnerable points:

Duke. “We should have been playing for money. You might have been less careless. How many times have I told you that you mustn’t leave so many of your pieces unguarded.”

Lady Glen. “I know that perfectly well, Duke, but in practice it’s impossible to guard all ones vulnerable points at the same time.

Lady Glen (Susan Hampshire) plays unguardedly, carelessly, at backgammon with Duke of Omnium (Roland Culver)

They discuss Lizzie Eustace’s diamonds and then a young nurse (Margaret Burnett) comes and takes over. Scene 2) Matching Priory, the vestibule, corridor and stairwell by the front door. Plantagenet home for the weekend; is told the Duke is bette; he tells of Phineas’s coming loss of office; first mention of their family:

Plantagenet. “Children are happy?”

Lady Glen: “Yes, they’re looking forward to seeing you.”

Scene 3) London, Parliament inside: Phineas’ last noble speech (dramatized from Phineas Finn, 1972 Penguin, ed Sutherland, Ch 75, pp 702-3).

“And so to a man born Irish, there can be no choice but one … Irish Tenant farmers are being grossly mistreated by their landlords, many of whom are English and what they plow back with such labor into their land is being legally filched from under their very noses (shouts of protest, men jump up, calls of “Rubbish” and “Sit down!”, Phineas speaks louder). “This this is my conviction and from it I must and will speak. As some of our members may be aware, this is not a happy thing for me (close up on Monk’s [Byran Pringle] aging face) that I should hold this conviction and feel bound to act at this time (Monk nods) but just causes do not always present themselves with a nice regard to a man’s convenience, and this must be my cause, let the consequences be what they may” (light “hear, hears”).

Scene 4) Scotland, Portray castle shot from an angle on the esplanade; we see a man riding up; Scene 5) on the banks and wild landscape surrounding (Portray castle on the banks of the river, Lizzie recites poetry, is accosted by her steward, Andy Gowran, who she asks to read a room for her cousin Frank’s coming visit. The one burlesque scene in the part. Lizzie making a fool of herself reciting Byronic (not Shelleyan as in Trollope so the politics is erased) poetry and her encounter with Andy Gowran (Leonard Maguire).

Lizzie Eustace declaiming Byron

Quite what is satirized here I still don’t know: women reading? the uselessness of blue stocking pretenses (useless to who I’d ask) Though the landscape is attractive, I don’t find Lizzie declaiming funny

Scene 6. London, Phineas office. A voice over of Mary (Maire Ni Ghrainne) as Phineas reads her desperate letter begging him to come now, Madame Max Goesler offers herself once more (see transcript)

We are presented with an alternation between Palliser-Phineas and Lizzie Eustace scenes or London/England and Scotland.

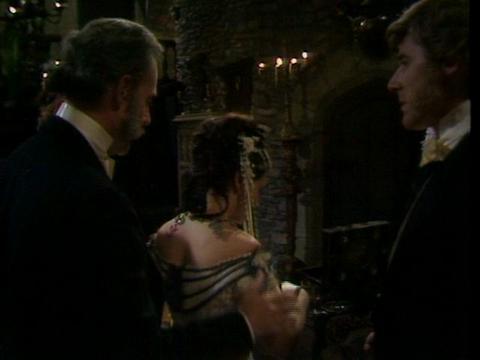

Episode 17, “Lord Fawn Visits.” Scene 7) Scotland, Inside Portray castle, dark front room. Long effective scene between Fawn and Lizzie Eustace, not burlesque at all, juxtaposed to Phineas and Madame Max, discordant in different ways see transcript). A melodramatic scene in which Jacobi holds his own as a determined sensible (it is sensible to give up the diamonds) man; the surroundings of the two are dark and gothic like; Lizzie is presented as wanting to please Fawn (the scene opens with a grating performance overdone—satire here I suppose—of “My Love is like a red, red, rose”). When Lizzie flees him she is in a corridor of dungeon-like stone, a kind of cave. His lines are sharp and perceptive enough, and hers parallel Kennedy’s (see below): as she will not give up the diamonds, so he will not give up Lady Laura. That she is the unsympathetic one of the scene is signaled by her push-up bra; such bras in film dramas usually the bad woman (nasty, aggressive) wears these absurd contraptions. Badel is the first in this series to sport this kind of thing; even Lady Monk was not squeezed and made absurd by this kind of undignified garment.

Scene 8) London Park. Phineas harrassed and depressed over his non-future, walks in the park, is menaced by violent Robert Kennedy who seems now to have become insane. Scene 9) London, Phineas’ office, Barrington Erle and Palliser come to collect Phineas’ resignation, Palliser maintains Phineas was wrong not to support party though his cause was just and Palliser sympathizes with Phineas (“There is no rancor …”) because it was so.

Phineas’s hand shook by Plantagenet Palliser (Philip Latham) who while he insisted on the resignation and says Phineas was wrong to vote against his party, says he holds “no rancour;” Barrington Erle (Moray Watson) standing by

Scene 10): Matching Priory, the duke’s bedroom, first we see him flirting with nurse who is complicit, then Lady Glen comes in and reads Dolly’s letter about Phineas’s flight from London and rescue of a “maiden in distress” (a jarring phrase) (see transcript).

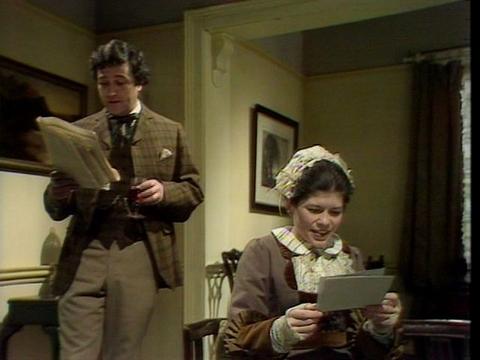

Episode 18: “Marie Returns,” Scene 11) Ireland, Phineas’s house or lodgings. Mary reads letter from Palliser giving Phineas a place in the Irish establishment and income (from Phineas Finn, Ch 76, p 717 letter and dialogue between Mary and Phineas):

Phineas reads newspaper about politics, Mary (Maire NiGhrainne) reads Palliser’s letter offering Phineas a place and income. He caring about where he’s left, she about them in the here and now.

Scene 12): Matching Priory, Lady Glen reading while expecting Marie’s (now Madame Max is Marie) return from Vienna; Marie told about Phineas’s “exile” into Ireland, his marriage and the pregnancy of the girl he married; Marie represses pain at sudden realization; she still evinces interest in elections as Phineas evinced in previous scene; we see neither Mary nor Lady Glencora cares, as what Mary cares for is Phineas’s salary so Lady Glen says Plantagenet may get a place because Mr Daubeny interested in ten-penny shilling); Scene 13: Matching Priory, Duke’s bedroom, Duke and Nurse at titillating play, interrupted by Lady Glen and Marie who “forgive” him (but will fire her); he says he’s bored and wants good company; now he has it in Marie.

Marie and Duke genuinely glad of one another’s company, Lady Glen stands by (not as confident that they will not marry one another as she would like to be)

Scene 14) Scottish countryside around Portray: Frank’s carriage glimpsed crossing old bridge; Lizzie again declaiming against rural landscape; a disapproving Gowran brings Frank (who calls Gowran a “canting Scot”) to Lizzie; when she begins to declaim Byron, Frank says they must go inside to talk “serious business” about the diamonds. In this his first appearance he looks unshaven, tired, but willing to toy with woman who plays with him:

Frank Greystock (Martin Jarvis) as he first appears close up to us and Lizzie

Scene 15) Scotland, inside Portray, and the dark front room; Raven zeroes in on a central pivotal scene of Frank & Lizzie’s relationship in ED and dialogue explains to us how Lizzie got diamonds (story about her beloved’s gift to her), what the conflict is and who between (are they heirlooms? what he says Lizzie can be compelled to do, “a big bailiff” will come &c); Frank reports that Lord Fawn will break his engagement with Lizzie if she does not give up the diamonds to the lawyers, and is told by Lizzie she will not permit this simply because she will not be “jilted” is embarrassed by Lizzie who aggressively clings to him, and when told by him he has an “understanding” with Lucy Morris, calls her scornful names and says Frank cannot afford to marry Lucy and she can do so much for him (much from Eustace Diamonds, 1976 Penguin ed SGill, Ch 23, “Frank Greystock’s First Visit to Portray,” pp, 245-52). Frank’s words and tone present him as an emissary from a reasonable decent establishment and Lizzie’s her as an isolated mean (in all senses) egoist. It’s this scene which dissolves on their kiss.

Frank attempts to reason with Lizzie about the diamonds; she’s not listening to him

Episode 19, “Frank’s News.” Scene 16) Ireland, Phineas’s house, Mary now pregnant and pushing on them weaker coffee (for the baby’s sake), saving (for his adulthood), with her outlining her plans for the childbirth; he’s more than resigns, accepts and looks with bright expression at her happiness over the coming child, but does not quite enter into it; reading his newspaper about the news from London, again a sense of people who live together live at a distance from one another too:

Phineas reading newspaper about English politics while Mary dreams of being a mother

Scene 17) Scotland, Portray Castle, Frank’s second visit. Inside the dark room, Lizzie waiting by window, he returns from London with information (again filling us in with plot information: the necklace is paraphernalia; nonetheless, she must hand it over; if she does not, she will have seen the last of Fawn; she replies, “Bother Fawn” and the man she wants is Frank, at which he replies that while in London he became “an engaged man”; she abuses Lucy (“prim morsel of feminine propriety,” “a towel rack,” which he resents and begins to gather his coat to return to London; she weasels and gets him to say as her “legal advisor” (no kiss now). This scene combines material from Eustace Diamonds, Ch 26, 271-76, Ch 31, pp 325-27.

Scene 18) Matching Priory, Drawing room, Lady Glen knitting, Marie looking out window looking melancholy.

Lady Glen knits and asks Marie if she is melancholy because she didn’t marry the Duke

Lady Glen’s mistaken perception (like Trollope’s Lady Glen, Raven’s is often not accurate in her assessment of what she perceives) is it’s not marrying the Duke that Marie is regretting; we know it’s the loss of Phineas & a youthful future with him.

Lady Glen. “Do you ever wish you had snapped him up?”

Marie. “The Duke?”

Lady Glen nods.

Marie comes over: “No.:

Lady Glen: “Yet I think you loved him.”

Marie: “I appreciate him. Always will.”

Lady Glen (looks at watch) Oh! (looks at watch). “Yes he’ll be waking from his sleep now. We must go up to him. Ho.” She looks weary.

Lady Glen weary and Marie sympathizes

Marie (walking around to face Lady Glen). “You are looking tired.”

Lady Glen. “Yes, yes, I am. Still it’s always a help when you are here ….”

Company, friendship, sympathy, the rare cordial of life. But then we move into what is apparently deemed comedy as they discuss the Duke’s “affection” for his nurse.

Scene 19) Matching Priory, the duke’s bedroom. An elderly and very plain woman (Olive Mercer) is focused on by camera; she has a grim expression on her face, and looks anything but friendly and kind. The young nurse was fired. A scene between an irritable Duke coerced into taking medicine; he is glad to see Marie and wants to know of Vienna, and says how dull it is here with no one with “a man to look at,” Lady Glen takes mild comic offense, and Plantagenet comes in for weekend; there ensues an outburst of frustation from the Duke as after Palliser tells of the interest the other party has in his ten-penny shilling, moves on to the news a trial about Lizzie Eustace’s diamonds started that day, and association makes the Duke demand “orange curaco,” which he finds despite his being “the Duke of Omnium,” no one is disposed to give to him until Lady Glen tells the “battleax” formidable nurse to go get it; she regards his death from curaco rather than “tantrum” as her choices. Not a very sympathetic remark to make. This makes an ironic and parallel contrast to Lizzie’s guests who visit her to get their bellies filled, with little care for their souls.

Episode 20, “Lizzie’s Guests:” Scene 20) Scotland, Inside Portray Castle, again the same dark room. The material for this scene is drawn freely and recombined from several chapters in Eustace Diamonds from Chapter 36 (the second volume, “Lizzie’s Guests”), and others, e.g., Ch 43 (cf pp. 428-29, ”’I should sell them,’ said Mrs Carbuncle”), Ch 45 (the conversation on the train to London). (See transcript). In brief, these rogue guests have arrived, tired, as weary of life as anyone in the part, and hungry too; but since there is no real frienship here, but the scene is strong on open discord, disillusion, and discomfort (Frank’s) and smooth hypocrisy (Mr Emilius supplies this as courtesy).

Scene 21) Matching Priory, again the Duke’s transcript, he moans and groans from the orange curaco and is now taking the medicine from Lady Glen’s bejewells hands (again see transcript), and the scene is a good contrast/parallel to these at Portray Castle. Scene 22) Scotland again in front room of Portray Castle, Lizzie and guests before going to dinner and again I transcribed some of it. It dissolves into Scene 23) Portray castle, Lizzie’s bedroom, we watch Patience Crabstick near the box, opening the bed, leaving us with a sense of something ominous waiting outside the window. 4) Scene 24) Finale of this part, again the front room, dark and gloomy, a highly theatrical scene which ends on Lizzie having her diamonds brought out and then refusing to allow Frank (cigar in his mouth) to take and put them round her naked shoulders, but encouraging Lord George to undertake the task.

Lizzie refusing Frank’s aid, offers her shoulders to Lord George (Terence Alexander) to put the diamonds on her

The atmosphere of the final scene is like some mystery story from the 1930s, with ominous over-the-top emphasis on the diamonds; what provides some relief is the depiction of Lord George and Mrs Carbuncle is not quite as in Trollope. In Trollope’s novel they are really a gang of heartless parasite, rascals, with Mrs Carbuncle a cruel materialistic ruthless bully over her illegitimate daughter and Lord George a genial rascal drone living off her who nonetheless has not lost sight of all morality. In Raven they are superficial rogues, playful, not altogether ill-natured as they give Lizzie good advice in the pragmatic way they understand; they are down on their luck, and willing to take what advantage they can of the fool Lizzie.

So in this scene, in Raven’s invented conversation Lord George shows some interest in political questions (more than Frank has, who seems as engrossed by the need for respectability as Lord Fawn). in Frank we see a different kind of male in a love relationship than we’ve had so far: he’s not really a hero type of any sort (George, Burgo, John Grey, Plantagenet, Chiltern, Phineas), but a sort of drone, weak before Lizzie except eventually to run away. Raven’s take on Trollope’s novel is that of the emasculating women and the corollary is the ridiculing myth of Hercules with his distaff which may be applied to scenes with Lord Fawn (though not in this episode), except to be without a high reasonable male at the center would be to undermine upper class male hegemony which the series never does.

To conclude, far from being satire, this episode is strong on grave melodrama. Raven characterizes Phineas Finn more than once as a very kind man with a strong conscience and he and Plantagenet Palliser are still the central exemplars, with Frank and Fawn as weak versions of them, seduced it seems by Lizzie Eustace. Lizzie is presented as hard, morally stupid and an utter phony, actually a very boring woman (but then none of the women are given any inner sense of themselves apart from men or things), a thankless role for Badel who does have a harsh register in her voice. I think Badel plays the woman as intensely dislikable finally and probably those who care about being faithful the author’s conception couldn’t complain about this. My objection is like Trollope Raven also does not himself provide a criteria for disliking her nor any sense of how she got to be this way—for say survival, out of say the values she was brought up with. The first name Raven gives her father, Admiral Greystock is “Horace,” and it might signal a self-indulgent epicure, but this is not at all developed dramatically.

In my experience it is highly unusual for a movie (whether on TV or in moviehousss) to be ironic. It seems that unlike plays, everything about the form works against this. We are not distanced because the film-makers do everything they can to erase the sense of a particular author (most of the time) and instead present us with an overwhelming sensual and visual experience meant to make us believe in what we are seeing; the appeal is to emotion and gut-level reactions. A play is prima facie symbolic; it does not overwhelm us, and we are continually aware that we are translating what we see into a conceived reality.

As I said I quite warm most to Mrs Carbuncle. She is a sort of Madame Max who has not had the insight or luck to do better than Lord George, though as the male characters specific to ED as presented by Raven, simply as a personality he might be as good husband material as Frank. He loses out because he’s no rich and well-connected man’s heir.

Mrs Carbuncle (Helen Lindsey) smiles at Lord George

Ellen Moody

See various links and a concise summary of 1:1-3:6, 4:7, 4:8, 5:9, 5:10, and 6:11.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Reading these blogs, watching a bit of Pallisers 7:13, and listening to David Case read aloud some of Eustace Diamonds, all with me, prompted Jim to remark that since Trollope’s novel is comic, Raven decided to make it into an interlude between the two Phineas novels which are (in his view) basically tragic. Phineas 1 ends in exile for Phineas and misery for Laura; Phineas 2 is at length about putting Phineas on trial for murdering a man, and delves his depression. Yes he's saved at the end by the improbable fairy tale of Madame Max and her money.

Jim suggested Raven tried to find ways to make an equivalent comedy for 20th century viewers, that a good deal of the comedy in ED is not funny to us any more or is heavy-handed. The narrator’s ironic asides are an exception; they are what makes one laugh. So Fawn was made in to an Osrick (the fop in Shakespeare's Hamlet), the scenes at Matching Priory are meant to keep us at a distance from this story, & Lizzie was turned into something of a clown too (consider all her fainting scenes).

He did think it doesn’t work; that the scenes at the Fawn residence & in London in Hartford Street with Mrs Carbuncle or in bed are stale and forced.

E.M.

— Elinor Jun 14, 10:00pm # - And in reply and for our readers, Jim listened to some of Eustace Diamonds read aloud by David Case when he was in my car with me the other day. He laughed and laughed whenever the narrator came on with his asides, reasserting the narrator’s sympathy for Lizzie or ironically commenting on how the world admired Lizzie but what was the reality of her.

I think Lord George was given the truest and quietly the most intelligent comments in 7:13 (except for the choral wisdom of Palliser and Madame Max), especially when he told Lizzie she was a parasite just like him, Jane (Mrs Carbuncle) and Emilius and had done nothing earn her keep, much less the diamonds. Lizzie is presented as child-like, a mean spoiled brat, so we return to the depiction of grown women as children when heroines, only here this one is nasty.

E.M.

— Elinor Jun 15, 7:17am #

commenting closed for this article