Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Pallisers 8:17: The Palliser family romance begins in earnest; a significant departure from _Phineas Redux_ (1) · 23 December 08

Dear Friends,

Once again 4 blogs on the 1974 BBC Palliser film series, screenplays Simon Raven, directors Hugh David and Ronald Wilson, produced by Martin Lisemore. I’m now past the half-way mark and am beginning to be able to be precise about its overarching major two stories. The emphatic climax of the secondary one, which swirls around Phineas, is the arrest and trial of Phineas Finn (played by Donal McCann) for the murder of Joseph Emilius (Anthony Ainley); the final episode of 8:17 is that arrrest.

The primary story is made the title Raven gave Trollope’s roman fleuve, “the Pallisers,” and 8:17 contains the first scene of the coming later part of their lives where Silverbridge (Roderick Shaw) emerges as a personality much attached to his mother, the Duchess (Susan Hampshire) and in conflict with his father, the Duke (Philip Latham). This scene shows how when accused of real emotional neglect of his sons the guilt of the father turns him into a bully, which behavior he is then ashamed of so he apologizes and vows not to ignore them in future, which however we see he proceeds to do.

It’s important for the series, wholly invented and brilliantly written and acted in itself so I provide a transcript and stills:

Episode 42: “Family Quarrel.” Scene 6: The Palliser front room in London (cont’d). The Duchess has been giving Adelaide Palliser (Jo Kendall) advice to marry Fawn since Gerard Maule (Jeremy Clyde) is “slippery” when it comes to proposing, and not good husband material at all if he did, and the door opens and Collingwood (Maurice Quick) comes in with the tea tray, the Palliser sons following him.

1. Group ensemble scene

Duchess. “Ah! tea. Heh. Heh! (Gerald [Barnaby Shaw] hurries over to sit close to his mother; Silverbridge walks over gesturing comfortably, with earnest expression on his face as he looks out at Adelaide once he sits down):

The Duchess gathering everyone around her for a comfortable tea time

Duchess. “The boys and I have been shopping, Adelaide.”

Silverbridge. “It’s made us very hungry.”

Duchess. “Yes, well, you must wait until your father gets here. (Showing her training them to respect the father, but she calls him from another room) Hurry up, Planty. The boys are hungry.”

In comes Madame Max or Marie Goesler (Barbara Murray) and Duke. He goes over to a head chair by the fireplace. Adelaide left standing.

Duke. “Oh my dear, a chair for cousin Adelaide.” (Gerald goes for it)

Duchess. “Marie, you sit over here by me” (including her in the family). (Silverbridge gets up, bows over her hand.)

Marie. “Silverbridge” (as he offers her his hand, upon getting up swiftly)

Silverbridge delighting Marie’s heart by his courteous gallantry

Duchess. “Ah, such an afternoon! We’ve been shopping in Bond Street, getting things for the boys to take …

Marie murmurs assent. Silverbridge goes over and brings a chair for himself to sit by Marie’s side.

Duchess: ” ... back to school (previously said to be Eton). Silverbridge needed some new britches for something called … uh … the Meadow game?

Silverbridge: “The Field game.”

Duchess. “Ah yes. The field game.”

Gerald. “There’s a big match in a fortnight and Silver will be playing. You’ll come, mama, won’t you. It ain’t far to Windsor.

Duchess. Murmurs and gestures yes, “mmm mmm” and smiles pouring tea.

Marie smiles as Silverbridge says (a little shyly): “You’ll come too, Madame Goesler.”

Marie. “Oh thank you.

The Duchess pouring tea.

Gerald. “And you too cousin Adelaide.”

Adelaide smiling kindly at him: “Yes!”

Duke. (Just a little grim in his face) “Oh, does nobody invite me? (pointed look, wags his head.)

Silverbridge. “Of course, we do, Sir, but we thought you’d be busy.”

Gerald. “You … you … alway are you know.”

Duke listening intently. “Oh it’d be better perhaps if Silverbridge too were more busy. Well, this field game, these britches, it’s all very well, but his mid-half report don’t speak too well of his studies and nor yours Gerald. Will you kindly pay me some attention, sir!”

Adelaide. “Oh/Ah well, cousin Plantagenet, all work and no play … ”

Duke. “I’m merely advocating some work, Miss Palliser.”

Duchess. “Planty, let us not talk of it now.”

Duke. “Well, it’s got to be talked about …”

Duchess. “Oh.”

Duke. ”... sometime” (getting up and beginning to pace in front of the fireplace). “Now the boys have not been near me all the time they’ve been here at home.”

Marie. (Attempting to reconcile and placate.) “Perhaps they realized you were a little preocupied, Duke?”

Duchess smiles (strained).

Silverbridge. “You were always locked away in you study, you know.”

Duke. “Uh, you’d only to knock. The door’s always open.”

Gerald. “But we did knock the day we came home and you said we must go away. You had someone important coming.”

Duke. “I had … and you should have come later.”

Silverbridge. “You weren’t very encouraging the first time.”

Duke. “Now what do you mean by that, Silverbridge?” (Voice getting menacing and angry). Are you implying that I was discourteous?”

Silverbridge. “Well, you were very short, sir.”

Silverbridge speaking up, bravely.

Duke. “You are accusing me of discourtesy, sir, and you will now apologize!”

Duchess looks yearningly & pityingly at Duke.

Silverbridge. “I’m not accusing you of anything, sir.”

Duke (fierce). “You … don’t you contradict your father, sir, you apologize as you are bidden.”

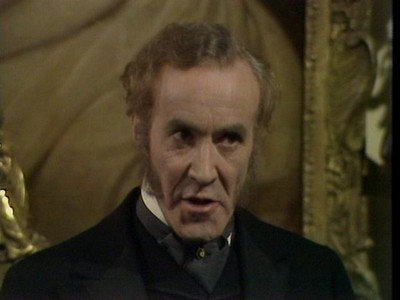

The Duke demands an apology.

Silverbridge: “I tell you I have nothing to apologize for. (A little sharply spoken, Turns rounds and heads for the door.)

Duke (shouts). “Silverbridge! come back here at once!”

Silverbridge. “I’ll not stay here and be bullied, not even by you.” (From the door, turned to go, strong voice but firm.)

Duke (shouting louder) “Youll come back here, sir, this minute!”

Duchess. (from her seat, strained voice). “Silverbridge, you will oblige me by coming back here at once and saying you’re sorry to your father.”

Silverbridge. (He walks back and stands behind the couch again.) “Since you ask me, mother, I apologize to everyone in this room. To you, mother, to you Madame Goesler, to you cousin Adelaide, to you father, to you too Gerald for making such an unpleasant scene.”

Marie whispers kindly. “Very nicely spoken.”

Duke though turns rigid. “And what else have you got to say, sir” (wants a form of self-abasement and humiliation, abjection from the boy)

Silverbridge. “I don’t see sir that I have anything else to say.”

Duke. “Oh is there not one special apology, due (shaking … )

Silverbridge (calm). ” ... to whom, sir?”

Duke (intensely) ”... to me, sir.”

Duchess looks very sad, and Silverbridge calm. (All realize they must accept this.)

Silverbridge walks quietly over: “I’m very sorry, sir, that I lost my temper and spoke back to you.” (It’s here that Silverbridge wins this scene.)

Instead he himself apologizes.

Duke (shaking still) ” ... mmm and lastly I too must apologize. I’ve been unkind and possibly unjust. I admit I have been very busy these past days. (pulls in breath sharply). and very difficult to come at … but I shall make a point of not being busy on the day of Silverbridge’s match …” He walks off, intensely. They never did discuss Silverbridge’s grades.

Duchess comes over to Silverbridge and rubs his shoulder affectionately, proudly.

The Duchess acknowledges Silverbridge’s self-control.

She walks out after husband. Close up still of Silverbridge, has face seen at a sharp angle, but not revealed from the side ends scene.

This is not a departure, but another in the series of fillings out of the Palliser story (showing Silverbridge in particular at different stages) not dramatized by Trollope, but (as it were) left assumed, and alterations in the direction of modernization. We need it here as the last two parts of the series will not be about the subject of Trollope’s The Duke’s Children, which centers on the results of the Duke’s awareness his now dead wife had not loved him as a lover/husband, a conflict with his daughter, Lady Mary Palliser, over her desire to marry Frank Tregear whom he identifies with Burgo Fitzgerald, and his conflict with Silverbridge, his grown son (Anthony Andrews) before and after the death of the Duchess.

Trollope’s Duke’s Children is about the Duke’s loneliness and deep disappointment in a life-long relationship of uncongeniality with the one person who got near to him and continually needled him; he misses her intensely all the while. It mirrors Trollope’s own relationship with his wife, and his 19th century assumption that marriage need not be based on love with the wife as the main affectionate companion of the husband.

In Raven’s film translations of The Duke’s Children, he makes the conflict with the father’s conflict with son central, and (as is seen in the next two parts, 9:18 and 9:19) the two characters, Duke and Duchess, a pair of people who now do love and sympathize with one another deeply, understand one another in a way Trollope’s characters never do, and form a genuine if sometimes naturally conflicted partnership in a modern way, even if (according to Victorian mores), the Duke gets the last word and is to be respected and obeyed particularly in public as the father and husband. The conflict in the above scene is over modern middle class ideals about parenting: is he a neglectful father, she an over-indulgent mother?

There is however a radical departure in the presentation of Phineas’s arrest for murder in this part. We have had the full-scale somewhat sympathetic development of the character of Mr Bonteen (Peter Sallis), not found in Trollope (see 8:16); now Raven does not inform viewers in any way that Phineas is not the murderer and that Emilius is. In the second chapter of Phineas Redux after the murder has been announced (Ch 47), Trollope’s narrator interrupts the narrative for this emphatic announcement:

“The reader need hardly be told that as regards this great offence, Phineas Finn was as white as snow. The maintenance of any doubt on that matter,—were it even desirable to maintain a doubt,—would be altogether beyond the power of the present writer. The reader has probably perceived, from the first moment of the discovery of the body on the steps at the end of the passage, that Mr Bonteen had been killed by that ingenious gentleman, the Rev. Mr Emilius, who found it worth his while to take the step with the view of suppressing his enemy’s evidence as to his former marriage” (Phineas Redux, 1983 Oxford ed., II:77-78)

Trollope goes on continually to remind the reader that Emilius murdered Bonteen in direct and indirect ways, e.g., giving details of Emilius’ comings and goings which alert Madame Max to go on her search for a second key, and showing us the inner workings of Phineas’ mind where we see how shamed and grieved Phineas is to realize his friends could think he could do such a cowardly treacherous deed—this murderer (Emilius) came upon Mr Bonteen from the back in the dark and the man never had a chance to defend himself.

In Phineas Redux, Trollope is careful to tell the reader from the get-go that Phineas Finn did not and could not (given his character) have murdered Bonteen. Trollope presents their hostility to one another, he has them quarrel, and he does indicate that it was partly Bonteen who stopped Phineas’s career from progressing (he was not given office) further once he returned to England. We are given scenes of personal dislike. But Trollope also makes Slide a continual irritant (more than in the film adaptation). Further immediately after the murder, the narrator of the fiction steps forward to tell us Phineas did not do it. Trollope wants us to know and remember Phineas did not do it for an important theme of his book hinges on this: the disloyalty and lack of belief of people in one another, of people who profess to be friends and care for one another.

This theme is important in other of Trollope’s novels, e.g., The Last Chronicle of Barset: surely, Josiah Crawley says to himself at first, no one would think from my character I could do such a thing (as steal) and some of his friends do use this argument to try to persuade others Crawley cannot steal; it’s of no avail with most characters as most of Trollope’s characters in both novels are willing to believe anything of one another really. The sense is (which Raven picks up on in Omnium’s justification for the suspicions in 9:19) they are half-willing to believe anything of themselves. Thus (I extrapolate) it would go against their view of the world (themselves, their self-esteem) to see someone else as not tempted where they might be tempted.

Trollope’s narrator can also make all sorts of other satiric points about people’s reaction to murder stories:

“When the House met on that Thursday at four o’clock everybody was talking about the murder, and certainly four-fifths of the members had made up their minds that Phineas Finn was the murderer. To have known a murdered man is something, but to have been intimate with a murderer is certainly much more” (II:84)

Finally,Trollope is undermining the rationale for capital punishment. While admittedly in Phineas Redux, he has his highly intelligent and competent lawyer, Chaffanbrass, argue for keeping harsh punishments, specifically capital punishment for forgery, Chaffanbrass is not Trollope’s mouthpiece for his ideals, but participates in this scene in a kind of debate over how to get people in the commercial marketplace to take things seriously (II, Ch 60, pp. 176-77), how to stop swindling (Chaffanbrass has just been fleeced over a horse he bought for his daughter). In Trollope’s first novel, The Macdermots of Ballycloran, an innocent man is hanged as a scapegoat for the Anglo-Irish community, and in other novels we are shown how the truth of what happened is not what the adversarial system in a court brings out; rather we get a community consensus on how the particular person is regarded and how the crime should generally be treated, and a resolution the successful lawyer manipulates to produce and all agree to pretend to believe in1, in public at any rate.

In contrast, Raven does what he can to put before the viewer all the circumstantial evidence for believing Phineas did the deed (the tall black hat, grey coat, bludgeon) and re-emphasizes before Phineas leaves the club how Phineas has feelings of wrath against Bonteen, and plays at killing Bonteen as a way of releasing his angry frustration. Raven has heightened and increased the number of encounters between Bonteen and Phineas. Raven’s Phineas pointedly twice says Bonteen is the man standing in his way. Raven did not have to make visible those parts of Phineas’s behavior which are the most highly suspicious. Trollope writes of Phineas before he left the club: ”’By George, I do dislike that man,’ said Phineas. Then with a laugh, he took a life-preserver out of his pocket, and made an action with it as though he were striking some enemy over the head” (PR, II, Ch 46, p. 57), and the film-makers show us the action:

Phineas acting out smashing Bonteen with his bludgeon.

Raven just before the murder shows Bonteen acting in good faith: he would have solved the trade problem had they put him at the Exchequer (none of this is in Trollope); he is much more insultingly deprived of the office he had expected, and yet after first getting publicly incensed, we see him working hard to right what the badly chosen and inexperienced Legg Wilson has made a mess of from the vantage of the Board of Trade. The opening scene where Bonteen accosts Dolly shows a man justifiably distressed and given the stonewall treatment by Erle who tactlessly tells him he lost the Exchequer over his behavior (drunkeness and boasting) at the Duchess’s. As it did a number of times during 8:16, the camera places us in Bonteen’s position.

We walk in with Bonteen and experience the scene from his perspective.

and it dwells on the phases of his anger and distress and writhing frustration:

A hard suffering face.

In addition, he is cruelly snubbed by the prince of Wales (something which does not happen in Trollope’s novel):

The Prince (Edward Hardwicke) pointedly snubs Bonteen, his face darkens again.

Raven’s Dolly doesn’t let us forget it: a little later Dolly feels prompted to express sympathy and reassure him, “Don’t take it personal old fellow,” and toward the end of the part, Dolly reminds Barrington Erle (and us) of this snub at the end of the scene in which Bonteen walks off into the street (to be murdered). Bonteen has gone to Prague and brings back evidence for Lizzie; even if he is sexually attracted to her, he is acting honorably on Lizzie Eustace’s behalf (and she is still characterized as not grateful, not wanting to pay the money the Bonteens can’t afford and are spending on her behalf); his quarrel with Emilius defending her is dramatized fully as it is not in Trollope. And his reward is to be murdered. No good deed gone unpunished as they say.

It may be said the film-makers did this to create suspense. But they could simply have included in the street scene some strong hints it was Emilius by giving us close-up shots of the murderer which throw doubt on its being Phineas, shown Phineas walking further away, without actually fully exonerating Phineas. The suspense could be, Will an innocent man be hung? That is the suspense in Trollope’s book. I think they were aware of how subversive Trollope’s story is and wanted to rid the story of that.

When we read Phineas Redux on Trollope-l for the first time, the person who wrote literal summaries for the chapters actually said that it’s not clear that Phineas didn’t do it, and tried to suggest Phineas could have. I suggested Trollope had obviated that, and when he persisted in saying no, Phineas could have done it, I quoted the the emphatic paragraph where the narrator said explicitly Phineas didn’t do it, and one near by where Trollope began to show how shocked Phineas was to think someone would think him so violent. The person was embarrassed and backed down, but I have come across the assertion elsewhere that it not only could it make sense to others that Phineas could have done it, but was even probable.

It may be said such people have been influenced by seeing the films—as people assert that Madame Max loves Phineas tenderly and sentimentally much earlier in the story than she does (from remembering the films, not the book). But I agree with John Wiltshire2 in his study of Jane Austen film adaptations that “one advantage of all such revisions [changes in the films from the books which change thematic inferences] is that the make public and manifest what their reading of the precursor text is, that they bring out into the discussably open the choices, assumptions and distortions that are commonly undisclosed within the private reader’s own imaginative reading process.”

This time I’ll do the descriptions and transcripts of the scenes with appropriate stills as part of an ongoing structural analysis of the whole film series.

Ellen

See various links and a concise summary of 1:1-3:6, 4:7, 4:8, 5:9, 5:10, 6:11, 6:12, 7:13, 7:14; 8:15, 31-33, 8:15, 34-35; 8:16, 36-38, and 8:16, 39-40

1 See my Trollope on the Net (London: Hambledon Press & Trollope Society, 1999):16-29; also on The Three Clerks, Orley Farm, and other novels with trials before magistrates and dramatizations of the workings of the law, R. D. McMaster, Trollope and the Law. (London: Macmillan, 1986).

2 I would qualify Wiltshire’s idea only by saying that what we see is the film-makers’ ideas about what the majority of film-goers, only some of whom have read the book (but who will be vocal about this), want to see as the vision and meaning of the book. See Recreating Jane Austen (Cambridge UP, 2001):5.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Nick on Trollope-l:

“While Ellen is beginning her detailed and brilliant close scrutiny of the Pallisers on a third viewing, I am still working very slowly through my first! And have reached Episode 17. As Ellen has previously observed this seems to be where Raven (I use Raven as shorthand) really and most obviously starts to deviate away entirely from Trollope. There are two very obvious aspects to this…

1) The murder of Bonteen. As Ellen observes…

>>everything is done in the film to make the reader believe Phineas could have done the crime. >Trollope’s Duke’s Children is about the Duke’s loneliness and deep disappointment in a life-long relationship of uncongeniality with the one person who got near to him and continually needled him; he misses her intensely all the while. It’s not about bourgeois parenting as ideals. But that is what these scenes are about.

2) The introduction of scenes showing the Palliser sons as schoolboys.

Now this second aspect may have been felt 'necessary' as a kind of preparation for the later episodes; audiences would be unable to accept the sudden appearance of the Palliser children as adults, which is in effect what we get in The Duke's Children. Ellen has already analysed this:

>>Trollope's _Duke's Children_ is about the Duke's loneliness and deep disappointment in a life-long relationship of uncongeniality with the one person who got near to him and continually needled him; he misses her intensely all the while. It's not about bourgeois parenting as ideals. But that is what these scenes are about.<<

With regard to the murder of Bonteen I have to observe that while I agree about the film-makers intention, I am far from clear that they succeeded. I am watching with Chris, my wife, who has never read the books and she instantly said that it wasn't Phineas who did it. Apparently the hair is wrong in the shot of the murderer (I didn't notice this - perhaps we could look at this shot closely in a second viewing Ellen? :)).

But the scenes in the club prior to the murder are horrible. Male behaviour at its preening,competitive, macho, boastful, crass, horrible worst. It is why I run a mile from all-male company. This may not be -- all right isn't -- Trollope, but it certainly has a truth and power of its own. I do think that Raven's own peculiar relationship to this kind of behaviour (love/hate?) is a powerful determinant here.

Nick."

— Elinor Dec 23, 1:14pm #

commenting closed for this article