|

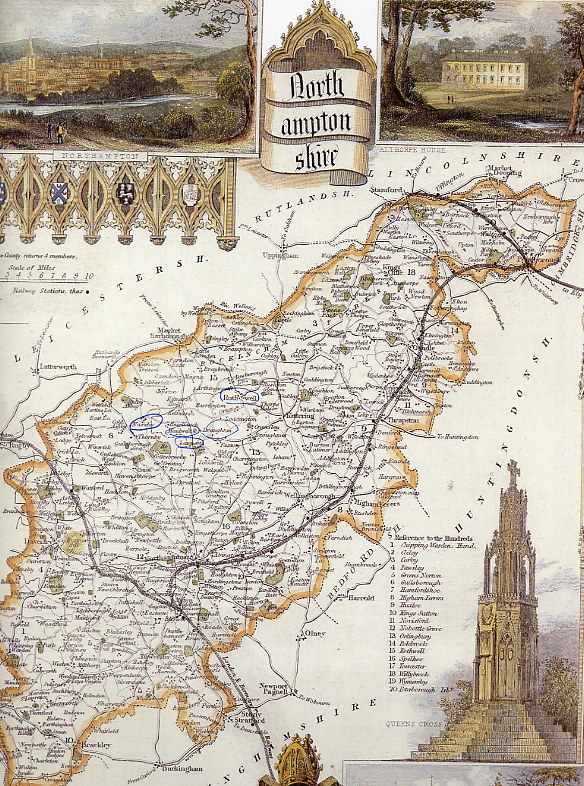

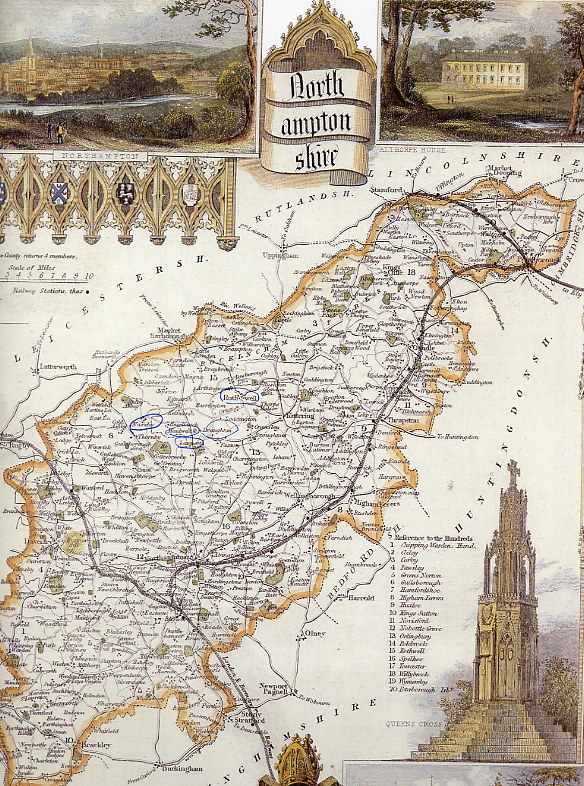

Nothing like victory to divide allies. Six years later the Kingsmills and Haslewoods went to it. This time Ann's paternal grandmother, Lady Bridget White Kingsmill, sues the above Sir William Haslewood; we should note that she did not sue to have the children but in the words of the court transcripts "management of the infants' estates" (control of the money). The question was what was a "fitting allowance" for each side, and this would be decided based on the outcome of Lady Bridget's suit for official guardianship of all three of her son's children (McGovern 11-4). This was by no means the first time Lady Bridget had gone to court; and from previous battles, we can see her interest is not in any individual's welfare, but to ensure the Kingsmill family's status and property, the lineage with which she identified her status. For example, between 1638 and 1647 litigation is a way of life whose aim is to ensure the family's continued financial basis; she sells Kingsmill manors to provide dowries for her daughters' marriages, neglected, so she claimed, under the terms of her husband's will. Her interest here was not her daughters so much, but, as Eames suggests, but to provide money to get them economically and socially suitable husbands. In 1652, she sued her own son, Ann's father, Sir William, over a piece of land. She is still writing about leases and rents left over from this and other cases four years later. We can sense the tenacity of her grasping character, her sharpness, and a kind of wheedling affection in two letters she sent to Ann's father. In 1656 she wrote Kingsmill: "Will, There will never be an end of mistakes till we come together, and then your owne letters will shew you that I followed your directions, though perhaps not your meaning." On one of his rejoinders a year later, she says: "there is but one point in it worth the answering," and signs herself "Your much abused mother." She is a businesswoman not much inclined to go into complicated--and worthless from her point of view--human matters (Eames 127-8). In January 1671 against her daughter-in-law's brother, she had a half-win for the Kingsmill interest. The court gave her the official guardianship of her son's two daughters, not saying, in the words of her most recent biographer Barbara McGovern, that "the girls should remain with their grandmother"--McGovern wants to believe that Ann's earliest memories come from living with Lady Bridget at Charing-Cross for which there is no evidence. The court said, in an attempt to soothe this troublesome woman, who was probably told the real reasons for her suit by the Haslewoods more than once, that the guardianship of the girls should go to the grandmother "as is proper," but said the boy should "continue where he is at present," with Sir William Haslewood "in the country." As the custody was now, so would the money be split (McGovern 11-4; Badminter 29-114). The implication is that until January 1671 the girls and boy have all been with their uncle in the country since their mother's death, but the girls may now be taken by the grandmother if she so chooses--and the court is pleased piously to assume that now that she has their allowance, she will herself, of course, do whatever is right and proper. So the answer to the questions: 1) where were Dame Anne's children when they were very young; that is, from the time of their mother's death until 1671; and 2) who took care of them are: 1) at Maidwell; and 2) Haslewood maternal relatives. Dorothy first, the child no-one had sued to have. Although her father, Sir Thomas Ogle, had official custody, and when he died in 1671, left the "wardship" (control of his daughter's marriage) to one Sir Richard Champion, contemporary anecdotes linking this young man to scandal in London and records of military service after Dame Anne died--as well as common sense--suggest baby Dorothy was not in his care (Cameron 231; Reynolds xx). Like her mother, Dorothy Ogle left only one document, and this too was her will. This will, signed on August 8, 1692, just before she died, as well as another of Ann's poems to her, "To My Sister Ogle From Kyrby Decembr 31th 88" (MS F-H 283, 38-40), suggest what numbers of studies of the seventeenth century record was the accepted custom was followed: Dorothy Ogle was taken in by her nearest maternal relatives, the Haslewood clan in Northamptonshire. The will itself reveals that Dorothy Ogle's position among the Haslewoods was not one upon which any cornucipia of objects had been lavished. She there defines herself as "of Maidwell in ye County of Northton, spinster;" she leaves her few personal belongings to those female Haslewoods and Kingsmills around her age who also grew up in the Maidwell nursery, as well as to the important Hatton of the moment, Lord Viscount Christopher. One of these female children, Ann's and Dorothy's first cousin, Elizabeth had 1685 become Lord Hatton's third wife. Even if all manufactured items in this period were expensive and difficult to come by and therefore regarded as near treasure--there is in these lines the pathos of the woman giving away the few cherished things which, Autolycus-like, she had snatched up: I give & bequeathe to ye Right Honble the Lord Viscount Hatton his Ladyes pictures then I give unto ye Lady Hatton my bible and common prayer booke then I give to my cozen Mrs Elizabeth Hatton my tea table dishes and gilt spoones [these toys suggest the small daugher of Lord Viscount Christopher and Elizabeth Haslewood, Lady Hatton, born 1686] then I give to my sister Bridget Kingsmill my bed then I give to my sister ffinch my cabinet and 5 yards of new-point, then I give unto my servt Mary Rice all the residue of my books, my watch & all my wairing Apparell [undecipherable] dressing glasse & Boxes and all the rest & residue of my Goods, Chattells & personal estate what soever I give and bequeath to the afresaid Lady Viscountess Hatton who I doe hereby ordaine & make the sole executrix of this my last will and testament ... (Reynolds xxi) In Ann's poem to Dorothy, which from its heading we know was written three and one-half years before Dorothy's death and from Kirby Hall, Northamptonshire (fifteen miles from Maidwell), where Ann was then living with the above-referred to Lord Christopher and Elizabeth Haslewood, Lady Hatton, Ann emphasizes her and Dorothy's long-grown deep abiding affection for one another; she remembers their "soft endearing life" together once upon a time, and assures her half-sister this unusual separation will soon come to an end. What had happened was that in the spring of 1682 Ann had left Northampton to come to London to become a maid of honor to Mary Beatrice d'Este (or Mary of Modena), who had returned from Scotland with her husband, James, then Duke of York. Probably at that time but certainly by March 19, 1687 (Cameron 46; Reynolds xxi) Dorothy had joined her older half-sister in London by becoming one of the maids of honor to Ann, then Princess of Denmark, James II's Protestant daughter by his first wife. The two girls were then together in London as they had been in Northampton, but when the Stuart regime began to lose public adherence, Ann as ex-lady to James II's wife and and wife to Heneage Finch, then a member of the entourage of James II, found herself part of one faction--that of James II and his Catholic wife--while Dorothy was part of another--James II's Protestant daughter. In November 1688 Princess Ann deserted her father; in December, Mary of Modena and James II (Turner 439, 444; Brown, Queen Anne's Letters 43-4) all too hastily decamped. Thus Ann and Dorothy were momentarily pulled in opposed directions, part of different factions. Ann returned to the Haslewood clan, specifically to her cousin Elizabeth at Kirby Hall, and wrote a poem to cheer and support the sister still in London, but expected home soon. In the poem Dorothy is again Teresa and Ann says in a voice which is made to ring with security: they will once again find "New arts ... new Joy's to try,/The hights of freindship, to improve." The poem's opening sets the tone of the whole: When, dear Teresa, shall I beIf Ann exaggerates or idealizes their childhood bonds, it is in the interest of kindness. But, of course, not just Dorothy, but William, Bridget, Ann also came to Northampton upon the death of their mother. We do not know which female Haslewood was nominally in charge. Perhaps at first the maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Wilmer Haslewood, but, as there is no mention of her by anyone, and as the court's words suggest Lady Bridget had claimed moral rights as "the" grandmother, this other grandmother was probably dead by the time the children arrived. We know that there were at Maidwell two unmarried Haslewood sisters: Jane Haslewood, who left 100 pounds to little William in 1664; and Bridget Haslewood still alive in 1671-3. But there is a more natural candidate for the female Haslewood presiding in the nursery: the 25-year old wife of the children's guardian, Elizabeth Ashford Haslewood who by November 1664 had in her care her year-old baby boy, the unfortunate Sir William Haslewood who was to be killed by his live-in cousin. This son was born October 27, 1663; within the next couple of years Elizabeth Ashford Haslewood gave birth to two more daughters, the Elizabeth who became Lady Hatton, and Penelope Haslewood, later Lady Seymour (Cameron 34, 30- 1, from MS F-H 2754, App. D; Longknife 19). Ann was not lucky in the survival rate of her parental figures. Her foster-mother, if foster-mother she was, Elizabeth Ashford Haslewood died before Ann was nine, and Sir William quickly remarried, by 1670 Cecil Ayshford [as it is spelled in documents] Haslewood, age 26 to Sir William's 28. She had a miscarriage in December 1672, and a son, Ayshford Haslewood, who was born November 13, 1673 and died age two (Ischam 175). It is this woman, Cecil, who is the somewhat obstreperous and occasionally violent head woman (so to speak) at Maidwell in an extraordinarily rich and important little book, to which we now turn. Its title (which appears on its first page) tells something of its content and rational: The Diary of Thomas Isham of Lamport [1658- 81] kept by him in Latin from 1671 to 1673 at his Father's command. The conscientious, if demanding, Sir Justinian Ischam, had made a bargain with his heir: if the fourteen-year old Sir Thomas would improve his Latin by keeping a diary of happenings and events (and whatever popped into his head on a given day), Sir Justinian would reward him with 6 for each year he kept the practice up. And so from November 1671 to September 1673 we have a diurnal record of the daily lives of the people living at and about Lamport Hall; as this includes revealing details about Maidwell and its Haslewoods, located less than two miles from Lamport, we have a vivid and, as far as it goes, true picture of Ann's childhood milieu. This diary also reveals that even after Lady Bridget won her case, she did not actually take her granddaughters to London to live with her. We will first deal with the sort of things Sir Thomas records about the doings of the younger Sir William Kingsmill (to distinguish him from his father) as the young male Kingsmill bulked much larger than his sisters or his parents in the mind of Sir Thomas--as is to be expected from another adolescent boy close in age. We hear of how the younger Sir William went to a cockfight with his cousin, the younger Sir William Haslewood; the younger Sir William Kingsmill is, apparently briefly, sent to the local Harborough Grammar school for instruction; he goes to Brixworth Fair with his uncle, cousin, and Mr. Saunders, another neighbor who lived in Brixton, and they see a Punch and Judy show (Ischam 177, 203, 207-8). The references to this boy are scattered throughout the diary. In fact, there is more about him than about the the younger Sir William Haslewood. There is much less on the girls, whom Thomas Ischam did not consider very important, and who came less often, but there is enough. Ann's older Kingsmill sister is once called simply "Mrs Bridget" --not the older aunt who would be given the dignity of her last name--but young Bridget Kingsmill (McGovern 15; Cameron 34-5). On April 20, 1672 young "Mistress Kingsmill" gossips in "the place caled Sow's Meadow, between Maidwell and Lamport" with Sir Thomas's sisters, Mary and Vere Ischam, aged sixteen and seventeen respectively. The fifteen-year old Bridget was anxious to tell her friends that "the Duke of Monmouth's brigade had been captured by the Dutch;" and, even better (from their point of view) "while they were gossiping they saw sixty new recruits passing towards London" (Ischam 105). Ann appears but once. She was only eleven, a child, and not likely to go off male brigade-, or girl-friend hunting on her own. Dorothy Ogle was but nine, and the cousin whom Ann turned to in 1689, Elizabeth Haslewood about a year younger; they were her companions. But on July 29, 1672, she was included in a dinner at Lamport Hall with Bridget and the Brixworth neighbor, Edward Saunders: Mr Saunders came to dinner with Mistress Bridget and her sister; we played bowls with him for a while. After dinner he told us that a large cave had recently been found in Whittlebury Forest by a a man who was looking for the stone quarries and nearly fell into it. Some gentleman or other heard of this new sight and went down into the cave with drawn sword. He was forced to stoop for some distance as the passage was so narrow, but came to a very confined space, where he saw whitened walls and an artificially constructed floor paved with stones. He also found a huge skull, bigger than those of two or three men of the present day. He saw other gloomy recesses but dare not venture farther. They think that it was once the den of a gang of thieves (Ischam 133).The kind of antiquarian curiosity caught here looks forward to Heneage Finch's later excavating propensities; when she was 57, in a comic ballad, "For Mrs. Catherine Flemming at ye Lord Digby's at Coleshill in Warwickshire," Ann would laugh at the archeological yearnings of her husband--"Your Antiquary still proceeds/To Spy thro Ages past"(MS Harleian 6316, 46). Sir Thomas is, of course, far more excited by the notion of a den of thieves nearby. After she won her court case from her daughter-in-law's oldest brother, Lady Bridget may have taken her granddaughters to stay with her for at least an extended visit (if only to save face), and one student of Ann's poetry, Ann Longknife, suggested that the girls lived for a time in with her at Sydmonton Court (29), but a few months before the above dinner party, in April 1672 to be exact, a year and one-half after she won custody of her granddathers, Lady Bridget White Kingsmill rented a farm at Maidwell from Ann's uncle, Sir William Haslewood. Since Lady Bridget doesn't turn up in the Ischam diary at all, one must assume she did not participate much in the life of the Maidwell-Lamport world; perhaps she was too old; she died near or at Maidwell on August 8th, nine days after the dinner party. Her lack of personal relationship to her Kingsmill granddaughters is suggested by the lack of any mention of them in her will at all (Cameron 36-7). We do learn something of the adults in the Haslewood household, and in particular, Ann's uncle, Sir William Haslewood, who emerges as a decent and reasonable if typical country squire. His worst fault is a more than occasional drunkenness--he hunts, shows off prize colts, takes part in local race meetings, is proud to have returned from London in one rather than two days. The sympathy Ann later displayed towards gypsies and beggars in various of her poems she learned from her uncle's behavior as Justice of the Peace for his county. On one occasion, he refused to bow to pressure and would not arrest a group of gypsies travelling through Lamport village (Ischam 163-4); on another he would not allow a woman who was said to have "assaulted" her husband to be humiliated publicly. The source of the marital quarrel was drink; an intoxicated husband had tried to fondle his wife and she had slapped him. Sir Thomas reports that Lady Cecil Ayshford Haslewood wanted to inflict the punishment known as "riding the stang" (dunking) on the wife as the wife remained defiant, but that Sir William refused out of consideration for the husband (Isham 155; Cameron 34-5). The modern reader might find nothing surprizing in the woman angry at another woman who has defied codes she obeys, and the man embarrassed for another male, but there is something surprizing in the flexibility the Haslewoods and Ischams and other neighbours display towards sexual preference in their own families. A group of entries suggests that not only was Sir William Haslewood's unmarried younger brother, "Major" John not heterosexually inclined, the family knew it, and anyone insulting the Major on this point risked economic devastation and bodily harm. Sir Thomas Ischam records that the Major never married (despite pressure for the sake of the family to do so) and never left Maidwell, but spent his life alongside his brother and his brother's children. The Major's one close companion was a male friend, Sir Thomas "Heselridge" or Hazelrigg, to whom upon his death John left money to buy a ring and gave his then dead older brother's picture. The editor of the diary, Sir Gyles Ischam, is uncomfortable with the whole business which he feels calls for explanations (160n3; 185n5); but at a drunken wedding celebration on January 5, 1673, it's clear the bridegroom, a Haslewood tenant, is not puzzled. Sir Thomas records that this young man said that Sir William Haslewood "had no one in his house but sodomites and whores." Incensed at an insult also meant for her, Sir William's wife, Lady Cecil ordered him to be turned out of his house, and two of three of them hauled him out and, seeking their opportunity, attacked him, giving him such a beating that he is not expected to live (Ischam 179).The family loyalty is perhaps commendable. Ann's response to this sort of scene may be found in her poetry in her several excoriations of both male and female drunkenness. There are pleasanter pictures of the Haslewoods and their visitors. Perhaps to the surprize of the modern reader who is familiar with the desperation of seventeenth-century people for ready cash and the lack thereof in this period, and the haughty fixation with niggling differences of class, we find the Haslewoods and friends not only sometimes generous with money, but considerate of those "beneath" them. Sir Thomas Ischam writes that another neighbor, Sir William Langham was "returning home from Maidwell" late in December, when his carriage fell into a ditch near our paddock [that is, between Maidwell and Lampton Hall], and while his horses were struggling to pull out the wheels stuck fast in the snow, they broke the pole, so they borrowed ours. Meanwhile Sir William sent others to summon men; they came and cleared the snow with shovels, and when this was done Sir William gave them eighteen pence with his own hand (Ischam 175).Sir William Langham's house, Walgrave Hall, was at the time not the Palladian mansion it has since become, but the formidable remains of "its seventeenth-century entrance gates" embody the self-image of an important man. It is true that Sir William Haslewood was not above taking an inheritance he should not have: when his servant, Mr. Osborn dies, after having refused to make a will, and it is found he had left nothing to his family, only 4 to two women," Sir William took "all the rest "above 500 according to popular opinion, besides some old leggings and many garments including shirts, which he was ever too miserly to wear (Ischam 81).This supposed avarice was not, however, evident on February 12, 1673 when near Sir William Haslewood's house [a Lamport Hall messenger] fell off his horse for some unknown reason and badly broke his thigh. Sir William Haselwood straightway sent for Mr Freeman the surgeon (Ischam 191)It may be that Sir William simply didn't like Mr Osborne's shirts. A fourteen-year old boy's vision is, of course, limited, but before we leave the diary, we ought not to neglect the descriptions of twentieth century Northamptonshire provided by Sir Thomas's translator, Norman Marlow, and then amended to its seventeenth-century appearance by his editor, Sir Gyles. First Norman Marlowe: The traveller across England from East Anglia to the more romantic West Country will always reach a point where it dawns on him that he is passing from one to the other; a lift of the landscape, a sudden view of woods and a far horizon, even a name on a signpost will bring this home to him. One such point is the little village of Lamport in the heart of Northamptonshire, eight miles north of the county town on the old road which leads to Market Harborough and continues as a by-road on the line of an old trackway up through east Leicestershire. Coming westward the traveller will have passed from the Fens through the small but sudden slopes of western Huntingdonshire to the more homely rise and fall of the country between Trapston and Kettering; and after Kettering the slopes become longer, and the landscape emptier and lonelier and the villages farther apart; until he clims a steepish hill, turns left into the main street of Lamport and sees, near the junction with the high road beyond, a landscape that is unmistakably of the west: a steep fall through fields to a valley and beyond it, receding into a blue distance, folds of meadow and wood (Ischam 53). Sir Gyles Ischam then focuses in on the open bare fields of the seventeenth-century, "studded with postmills," when a post-mill on a mound to the south of Lamport was "a prominent landmark" across the whole countryside near Maidwell. He also adds that in the seventeenth- century there was a miller at Maidwell, and the main old Northampton- Market Harborough road, the artery of communication to London, was very bad, and its side-roads, "mere cart-tracks." The church at Lamport Hall was entirely medieval, except for a chancel Sir Justian rebuilt in 1652; the rectory was Tudor, Lamport Hall an Elizabethan manor-house, but with a Tudor great hall, screen and gallery, all built round a courtyard. Maidwell was not much different (Ischam 23-4). Such was the landscape and what we know of the people Ann grew up among. For a picture of the inner workings of a Caroline house such as Ann participated in (whether Maidwell or Sydmonton), G. M. Trevelyn's economic analyses of the well-known Verney household at Claydon, Buckinghamshire, will suffice: The great house provisioned itself with little help ... The inhabitants brewed and baked, they churned and ground their meal, they bred up, fed and slew their beeves and sheep, and brought their pigeons and poultry at their own doors. Their horses were shod at home, their planks were sawn, their rough ironwork was forged and mended. Accordingly the mill-house, the slaughter-house, the blackmsith's, carpenter's and painter's shops, the malting and brewhouse, the woodyard full of large and small timer, the sawpit, the out-houses full of all sorts of odds and ends of stone, iron and woodwork and logs cut for burning--the riding house, the laundry, the dairy with a large churn turned by a horse, the stalls and styes for all manner of cattle and pigs, the apple and root chambers, show how complete was the idea of self-supply.Ann's responsibilities (and thus her education) would have included: spinning at wool and flax, fine and coarse needlework, embroidery, fine cooking, curing, preserving, distillery, preparing medicines from herbs .. . [and] the making of fruit syrups and homemade wines from currant, cowlip and elder, which played a great part in life before tea and coffee began to come in at the Restoration (248-50). If Ann stayed at the richer Sydmonton during a visit or visits to her paternal grandmother, as Longknife suggests, she might have found panelling displacing the tapestries of Maidwell, though from a poem Ann wrote at Longleat many years later we find tapestries were still commmon even among the most wealthy into the eighteenth century. At Sydmonton at least there would have been the kind of elaborate plaster-work and tables with ornamental legs--on carpets rather than rushes--that provided the housemaid in her fable of "The Goute and the Spider" with dust [n4]. In both houses, Maidwell or Sydmonton, the stool was the common seat; it could be covered with velvet, but chairs were for adults; and the enormous magnificently-carved bed and cupboard still reigned supreme. A cabinet, such as Dorothy left her "sister ffinch," would be coveted (Chartier 228; Marshall 39-48; Trevelyn 246-7): it was a small item with a lockable door or drawers, as we shall see suitable for keeping her poetry in. And while in London (and where transportation was available) "most hearths burned coal," the wealthy preferred wood (Perry 29; Trevelyn 188-9). In a poem Ann wrote March 25, 1702, "An Apology for my fearfull temper in a letter in Burlesque upon the firing of my chimney At Wye College [Kent]," she exorcizes her an eruption of nervous dread by a comic retelling of how a roaring fire in an unswept chimney at Wye College had come to terrify her and led her to rouse the whole house; her comment that the situation arose in the first place because the Finches would took pride in large fires "of which No FINCH was e'er a stinter," suggests wood was a luxury (MS Wellesley 99). It's a good bet that nearer to London, the Kingsmills at Sydmonton, used coal, and that though land-bound in Northamptonshire the Haslewoods--who perhaps cleaned their chimneys more often than the Finches--also cooked and kept warm with coal. |