|

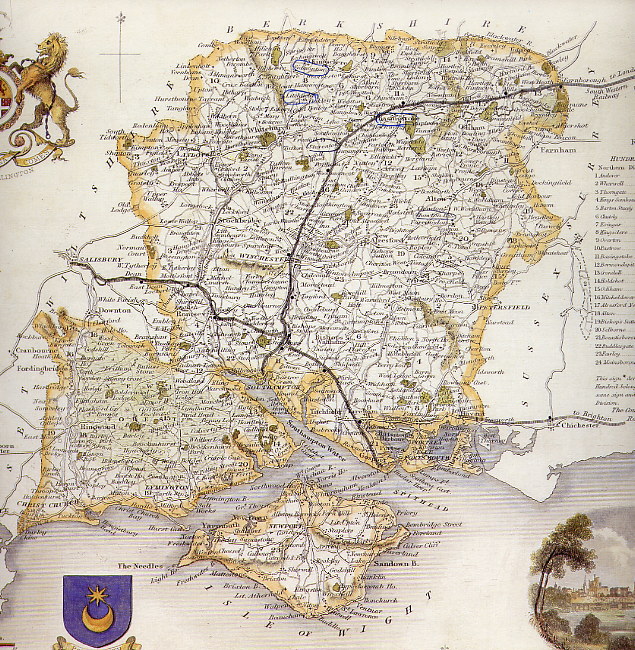

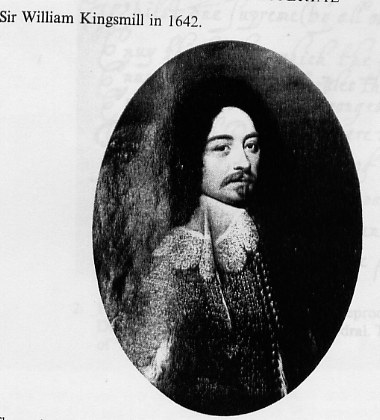

On February 21, 1654, in the parish church of Maidwell, Northamptonshire, Sir William Kingsmill, heir to Sir Henry and Lady Bridget White Kingsmill, married Anne Haslewood, one of the nine children of Sir Anthony and Elizabeth Wilmer Haslewood. He was 41, she 24. Although 24 was not uncommon for a first marriage of a woman of the middling classes, 41 was a bit old for the first marriage of an heir. In his 30's he had been a handsome slender man, with swarthy skin, dark curly hair clustered tightly about a round face, and dark wide-apart almond-shaped eyes, a long "ski" nose, elegant cavalier mustaches over flat lips, and in her 20's, his third daugher Ann looked very much like him, also slender, with dark curly hair and dark almond-shaped set- apart eyes, and a flat if smaller mouth, differing in fact only in her fairer smoother skin and heavier higher bridged nose (cf. the two miniatures in Eames 153 and Stuart Lives 154). We do not know what Ann's mother looked like, but pride of lineage, of "blood" and position, was something she and Sir Willliam shared and identified with--and this they did pass down to Ann. The one thing the seventeenth-century historian and clergyman, Thomas Fuller, thought to write down about the Haslewoods was that they were a "very ancient" and "worshipful" lot; like others of their middling gentry type who were not as wealthy or well-connected as they would have liked, the Haslewoods took pride in an old name and presence in Northamptonshire. It was in Ann's lifetime that the family disappeared from Northamptonshire records. A skidding down which they had neither the assets or kin to offset had begun in the 1640's when Ann's father had twice to pay the usual bribes parliament exacted of people thought to be royalist (or who could be so accused); and this was certainly exacerbated by unexpected early death of Ann's mother's oldest brother, Sir William Haslewood, followed hard upon by a disaster, the murder of his oldest son by Ann's brother, but of this more later. The microscopically-learned Sir Gyles Ischam suggests that Ann's uncle Sir William had hoped his younger brother, John--"the Major"--a bachelor, would take over his place, but he died without issue, and some time after Sir William's death, the Haslewood house "was sold and became the County Gaol" (Ischam, 28; Cameron 30-2). Of the Kingsmills much more is recorded: they were wealthier and have lasted into our own century. But in this period they too chose to emphasize not their wealth, but a claim to ancient genealogy and prestigious and powerful positions that stem from wealth. The Kingsmills traced their line back to the thirteenth century, and liked to tell stories of personal services to kings and queens. Records of sums of money, rents owed, taxes paid on enviable amounts of land do go back to Henry VII, although the claim in Charles I's time that Sydmonton was theirs for four generations back was stretching it a bit. Still Ann's Kingsmill background included a number of learned, literary, and reputedly clever people and were an important factor in the family's rise to a mild eminence in the sixteenth century. It is in this era that firm records of individual achievement begin. There was, first, from the nine sons and three daughters of Sir John (died 1556) and Constance Goring Kingsmill, the eldest son and heir, a Sir William who held significant offices under both Elizabeth and James I (sheriff, Justice of the Peace, &c for Hampshire), and was written down as "the wisest gentleman of his country." Then there was Andrew Kingsmill, described by a sub-warden of All Souls as "a phoenix among lawyers" (by the later sixteenth century the family had become one among a group of family dynasties at the Inns of Court), and "a rare example of godliness among gentlemen"--he was a puritan divine who left a slew of theological tracts. The seventh son, Thomas Kingsmill, became Regius Professor of Hebrew at Oxford. The patriarch, Sir John had acted successfully as a Royal Commissioner during what is often labelled "the dissolution of church properties," but is more honestly described as the giving out of spoils to the right people; in fact, Sydmonton was such a prize, a hard- earned reward for probably dicey work (for a photograph of the house now torn down, see Eames 155). Other sixteenth-century male Kingsmills were judges; the females married educated church dignitaries (Eames, 126-7; Prest, 37; Cameron 27-9; Reynolds xviii-xix; DNB, "Kingsmill, Andrew" and "Kingsmill, Thomas," 183-4). Ann's father, born in 1613, was himself an unpublished poet. This is significant. It suggests that the kind of rigorous learning necessary not only for land acquisition in the courts, but for for poetry too was encouraged in the Kingsmill circles. And talents are inherited. Also, interestingly, Ann's father's poems reveal a strong similarity of outlook between father and daughter, an inheritance, which, if familial and not personal--Sir William died in September 1661 when Ann was but five months old--was nonetheless real: in both poets we find a conservative tone of mind; classical and serious modern learning; love poetry in the tradition of Sidney and Donne, which assumes a small "coterie" and is autobiographical; political satires which recall later seventeenth century poets (i.e., Waller), and a kind of poem Sir William's generation called a "promenade" and Ann's "a landskip," but Kingsmill's modern editor, John Eames, labels simply "poems of country life." Ann's spontaneous arrogance upon occasion, as when she mocked John Gay's Trivia, or The Art of Walking the Streets of London ("Gays trivia show'd he was more proper to walk before a chair, than to ride in one," so no wonder he gave such excellent advice...), for which she would pay, is rooted in family feeling which finds explicit expression in Kingsmill's assertion that only those who are "gentle--" "Whose blood runns pure and free"--can ever attain a really noble style; those "of mean degree"--"whose mudd of generations thicke/Whose low conceptions fowle"--write without a "soule" (Eames 152; Bowyer 198). Numbers of Ann's father's poems look forward to hers, and since Sir William Kingsmill's poetry is not easy come by, I pause here to suggest something of Ann's heritage from her father. There is, first, a group of poems in which Sir William ponders the landscape as an emblem for social and political world in a mood Eames calls characteristically "despondent," a technique and mood also characteristic of Ann. Sir William complained that in 1642 he was forced into public life "under menace of ruin," and he did not clearly opt for either side in the civil war; in a felicitous phrase Eames remarks that in Kingsmill's "mode of life" we find "the conservative's desire to preserve social and political order;" in his verse, "his personal determination to preserve the sanity of his private existence" (Eames, 134-6). "Satyre 4," "Of Sunnshine and snow in the ayre on New yeares day" moves slowly; like some of Kingsmills' daughter's it is poetry of (I quote Eames) "resignation," "a very quiet, sad and personal reflection on the troubled times:" Welcom sorrow, suffering's light, There are also a group of love lyrics (to a woman whose marriage and pregnancy in the later 1640's did nothing to cool Kingsmill's ardour, one Catherine Cecil, Lady Lisle). One stanza must suffice to testify to a lyrical delicacy, attention to visual detail, the intense care, and only somewhat displaced autobiography which lie behind Ann's lyrics. It is a pastoral praise of an idealized lady: There when shee walkes the birds doe singBut the "quiet voice of reverence" Eames finds in the above idealized vision of the lady was mostly lost in Ann's generation. The much longer "A description of his Parke" was written in 1651 when, like his father-in-law, Sir Anthony Haslewood, before him, and his own mother too (though characteristically, Lady Bridget held out until 1655), Kingsmill compounded for his estates. It too belongs to an autobiographical group of poems, this time on Kingsmill's economical and political tribulations (e.g, "Driuen from his house by warrs and returning again" dated 1645). Eames compares "A description" to Marvell's "Upon Appleton House" (145), and there are sections which compete in exquisite naturalistic and sensual beauty with some of Ann's most admired landscape verses. Two sections tell us something about Kingsmill's life; in one he may be justifying to himself his willingness to pay up, but it reads like a complaint about the expense of turning a real piece of hard ("chalky") land into a park. Here he asks himself why he does it: This Rocky Fabricke that with furrowes lyesUntil, of course, Sir William came. Kingsmill's frankness is refreshing when one has read entirely too many panegyrics on vast estates said to be ancient, though some might see in the above sentiments the truth that the owner inside see differently from those on the outside of the fence. Somewhat later in the poem we find that, again like his daughter after him, Sir William was in the habit of wandering in tree- lined groves where he would meditate verses; one notices the scepticism and perhaps Shakespearean allusion (to Henry IV) in the passage which informs the reader that in 1643 from Sydmonton hill Kingsmill witnessed the bloody and terrific (complete with amassed armies) battle of Newberry: A walke of Oakes, with Pines and Wallnuts grac'dEt in Arcadia Ego. The Kingsmill-Haslewood marriage was, of course, an altogether quieter affair which left few documents. It lasted seven years; from it three children survived: William, Bridget, and Ann. The date of William's birth is disputed: either he was born just after the marriage ceremony, spring into summer 1654, and therefore its cause; or he was born some six years later, late 1659, early 1660. Bridget was born in June 1657, and Ann April 1660. She was born in spring. As Sydmonton was, as we have seen, Ann's father's hard-kept seat, the couple resided at Sydmonton. It was nearby (in Suffolk) that her mother met her next husband, whom she married eleven months after the death of Sir William. For, alas, on September 3, 1661, Sir William was buried at Kingsclere; by his will he had left his wife in charge of his estates (which were to go to his son), and provided the two daughters with respectable dowries for people of their class. Bridget's was the equivalent of three years income for an average knight of the period; Ann's the equivalent of two (McGovern 9-10, 228-9; Eames 137-8; Cameron 33-4; Reynolds xix-xx), though, as we shall see, not only was this nothing wealthy nobles would jump at, it was precisely the sum which enraged Heneage's father when his eldest son married without his permission a young woman whose relatives offered this (to him) paltry and wholly inadequate sum. In fact, Ann's mother did not find managing her son's patrimony easy, for a year later, on September 1, 1662, she assigned the manor of Draughton (in Northamptonshire) to other owners; it was later claimed in the Court of Chancery that before her marriage to Sir Thomas Ogle, she also made over her interest in Kingsmill estates to Sir Robert Mason, Kingsmill Lucy (southern gentry related to the Kingsmills), Sir William Haselwood (Ann's uncle, her mother's brother), and Sir William Langham (the husband of her mother's deceased sister, Elizabeth, and therefore a second representative of the Haslewood interest). It should also be noted that from his will it is clear Sir William meant his wife to use his son's estates to educate his daughters as well as his son (Cameron 33; n1, using Bacon-Cornwallis letters: how difficult it was to collect one's jointure). About Ann's first one and one-half year of life, we have one brief statement and one as yet unknown longish poem, "The Retirement," both by her. Ann's brief statement appears in an early poem to her younger and half-sister, Dorothy Ogle, "Some Reflections in a Dialogue between Teresa and Ardelia" (MS F-H 283, 18-25) [n2]. Apparently baby Ann was just about forgotten, lost in the shuffle of death and re- marriage and trouble. She would have lived in the home of her wet-nurse rather than having the more privileged (and safer) status of a baby whose wet-nurse lives with or near the family, and as Badminter reminds us, "the more modest the child's beginnings the farther away he would be sent." The scrutiny and supervision provided for a third daughter was not apparently exacting (Badminter 39-52). Dorothy--as the title of the poem indicates here called by her poetic pseudonym, Teresa--reminds Ann-Areta--the original name beneath an "Aredelia" which has been written over it in the line--how dependent on God's kindness Ann has always been; how when she was very young only He did not forget her: "When thou didst yet, upon the breast depend,/Who was thy Father then, and who was then thy friend?" (MS F-H 283, 49-50, n3). If we remember Blanche Dubois, we can judge how far such kindness went, and how vulnerable Ann knew herself to have been. "The Retirement" appeared as one of nine anonymous poems by Ann which appeared in an anonymous 1701 volume of poetry entitled A New Miscellany of Original Poems on Several Occasions whose editor is now thought to have been Charles Gilden. Four of these poems have long been recognized as Ann's because they occur either in the major manuscripts of her work or the 1713 volume of her poetry (also originally published anonymously); but five have been missed. I must until Part Two of this study hold off the argument for attribution from external evidence and from the oddities which have been noted in the pagination of the volume just around the pages on which the four known poems are printed [n2]; here we will dwell just on the autobiographical detail which concurs exactly with all we know of Ann, noting only that the style and mood are exactly that which we find in Ann's other melancholy verses of the 1690's. The poet is trying to explain why she has retired, why withdrawn from the world. She begins with her infancy, and tells of the deaths of first a father and then a mother: Abandon'd, helpless, and alone I came The literal references are again obscure or left enigmatic. Why if the mother had died sooner, the child would have died is not clear. There are some beautiful lines in this poem. The poet speaks of "the World's bright dawn," a classical golden age now long gone, as her parents' youth was long gone when they died. She insists their death was traumatic to her, that the sorrow of her early years stayed with her. She then inserts in quotations a long passage from another obscure poem as she mourns the necessity to live on. She ends urging herself to submit to God's will, but apparently cannot and describes herself as "lost," unable not to wish for death. In this the poem recalls the thought which of Ann's powerful closing couplet in her "To Death:" "Gently, thy fatal Sceptre on my Lay,/And take to they cold arms, insensibly they Prey" (MS F-H 283 6). The versification is inferior, the poem uncontrolled in mood and therefore maudlin, but it shows Ann's preoccupation with religion came from doubt not certainty: We know not what his will commands us here,The poem reveals importantly that Ann, unlike others of her generation, was willing to talk about socially-unacceptable vulnerability and melancholy in her private poetry, even if she was not willing to publish it. It also shows us specifically that what is often said in print-- that people of earlier generations somehow escaped primal needs for maternal and paternal affection--are not so. They just rarely admitted to such things. The license for the marriage of Ann's mother to Sir Thomas Ogle, was issued on October 7, 1662; this time the bride was "above 30," the groom 24. There was time for the one daughter, Dorothy, born sometime in 1663, before Dame Anne Haslewood Kingsmill Ogle herself died. That an affectionate, trusting loving relationship had subsisted between her and her second husband can be witnessed in the only personal words she ever left, those in her will (dated September 1, 1664) in which she tried to protect her children after her death by stipulating that they be brought up as a group together under the care of her second husband. She wrote (or dictated): And out of the assurance I have of the prudent love and care of my deare husband Sir Thomas Ogle I doe wholly give assign and remitt and bequeath the education and government of all my Children unto my deare husband Sir Thomas Ogle to be brought up in the feare of God and good nurture according to their Quality as he in his Dyscretion shall think fitt (McGovern 229-3). While, unhappily or not (we know very little about the character of Sir Thomas), no-one in either family was inclined to leave the Kingsmill children in the hands of Thomas Ogle, it will appear that Dame Anne's desire to keep "all" her children together, probably to foster emotional bonds and economic obligations to be relied upon, were followed by Ann and even her husband, Heneage when after her death we find him attending to his "newphew Kingsmill," Ann's older brother's mentally defective only son (MS F-H 282, unpaginated 9r-v). The reasons for not leaving them with Thomas Ogle are obvious. First the three Kingsmill children came with moneys which were meant to be spent on an "education" whose criteria were left undetailed. They were, in fact, too much wanted by all three groups (Ogles, Kingsmills, and Haslewoods), though the motives for the battles over guardianship, as shown in many lengthy court documents, were far from disinterested. If we believe the Haslewoods and Kingsmills, the Ogles grabbed- -Sir Thomas unlawfully "for his own use" retained--the income from the estates and refused even to pay legitimate debts; the Haslewoods and Kingsmills accused the Ogles of forged documents and even wife abuse-- Dame Anne's will was "unduely obtained and not long before her death." The date the case began--shortly after Dame Anne's death, November 1664--is of interest because it is in these court papers that we discover Ann's mother's oldest brother, the Sir William Haslewood who died younger than expected, had almost immediately been made guardian of Ann's mother's three Kingsmill children; six months later, the Kingsmills and Haslewoods beat out the Ogle claims (McGovern 11-12; Cameron 33-4; Reynolds xx). |